#science illustration

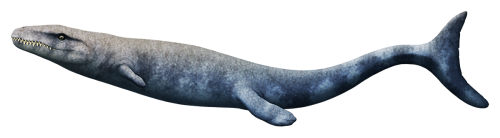

Blesmols, or African mole-rats, are a group of rodents adapted for mole-like burrowing. Closely related to the more famous naked mole-rat, these little mammals have reduced eyes and ears along with incisors that protrude out even when their mouths are closed, allowing them to excavate tunnels primarily using their teeth.

One of the earliest known fossil blesmols is Bathyergoides neotertiarius here, from the early MioceneofNamibia about 20 million years ago. For almost a century this species was known only from teeth and partial skull remains, but recently a partial skeleton was described giving us a better idea of its overall appearance and lifestyle.

Bathyergoides was a fairly large blesmol, around 25cm long (~10"), and was already specialized for tooth-digging with a skull very similar to modern forms. It had powerful muscular forelimbs that would have been used to push back loose soil while burrowing, but unlike its living relatives it also had a long tail and relatively slender hindlimb bones – with anatomy suggesting its legs were used more for stabilizing its posture than for actively digging.

It may have had a less subterranean lifestyle than modern blesmols, digging out extensive burrows but still foraging for food above ground in a similar manner to modern semi-fossorial rodents like giant pouched rats.

———

Nix Illustration|Tumblr|Twitter|Patreon

Post link

Amargasaurus cazaui was a sauropod dinosaur with a very distinctive-looking skeleton, sporting a double row of long bony spines along its neck and back. It lived in what is now Argentina during the Early Cretaceous, about 129-122 million years ago, and was fairly small compared to many other sauropods, reaching about 10m in length (~33’) with a proportionally short neck compared to its body size.

And despite being known from fairly complete skeletal remains there’s still a lot we don’t know about this dinosaur – especially what was actually going on with those vertebral spines. While it’s sometimes been depicted with skin sails over the spines, for the last couple of decades the general opinion has trended towards them being more likely to have been covered by spiky keratinous horn-like sheaths.

But recently that’s been brought back into question. A detailed study of the microscopic bone structureofAmargasaurus’ spines shows no evidence for keratin attachment and instead found textures associated with skin coverings, along with an extensive web of ligaments connecting the spines to each other along each row.

So maybe it had big flashy sails after all!

———

Nix Illustration|Tumblr|Twitter Patreon

Post link

It’s been a while since I last showed off some of these, but here’s some more commission work I’ve done for PBS Eons:

- Themetriorhynchid marine crocodilians AggiosaurusandCricosaurus, from “When Crocs Thrived in the Seas”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vgqs_9BBX10

And…what’s this?

A familiar Scutellosaurus makes an appearance in a recently-published children’s dinosaur book!

———

Nix Illustration|Tumblr|Twitter|Patreon

Post link

April Fools 2022: The Aquatic Dinosaur That Wasn’t

So,Spinosauruswasn’ttechnically the first known aquatic non-avian dinosaur.

That title instead temporarily went to Compsognathus corallestris.

While the idea that hadrosaursandsauropods were wallowing swamp-dwellers had been completely abandoned at the start of the Dinosaur Renaissance, the new view of dinosaurs as active sophisticated animals led to a surprising aquatic hypothesis during the early days of this paleontological revolution.

A specimen of the small theropod Compsognathus discovered in southeastern France in the early 1970s was only the second skeleton ever found of this dinosaur, and came over a century after the first. It was initially thought to represent a new species since it was about 50% larger than the German specimen of Compsognathus longipes, and it seemed to have something very unusual going on with its hands – its forelimbs were somewhat poorly-preserved and distorted, and had traces of some sort of large fleshy structure around the hands that was interpreted as representing elongated three-fingered flippers used for swimming.

This wasn’t necessarily as ridiculous of an idea as it might sound. Compsognathus lived during the Late Jurassic, about 150 million years ago, at a time when Europe was a group of islands in a shallow tropical sea. A semiaquatic dinosaur specialized to swim and dive, hunting the abundant aquatic prey in its environment, and easily able to island-hop all around the European archipelago seemed at least somewhat plausible, and reconstructions of fin-handed C. corallestris even appeared in several popular dinosaur books of the time.

But it didn’t last.

Within just a few years doubt was being cast on this idea, and further studies of both known Compsognathus skeletons in the late 1970s and early 1980s concluded that C. corallestris was actually a fully-grown adult individual of the juvenile C. longipes. The French Compsognathus had normal-looking hands for its kind after all, with two large clawed fingers and a vestigial third finger, and the “flipper” impressions had just been ripples in the fossil slab.

For a long time after that the general view became that there just weren’t any aquatic non-avian dinosaurs at all – but more recent discoveries like the new Spinosaurus material and Halszkaraptor are starting to suggest that some of these animals were much more at home in the water than previously thought.

Something resembling Compsognathus corallestris might still surprise us in the future.

———

Nix Illustration|Tumblr|Twitter|Patreon

Post link

Retro vs Modern#23:Spinosaurus aegyptiacus

Spinosaurid teeth were first found in the 1820s in England, but were misidentified as belonging to crocodilians. It wasn’t until nearly a century later that Spinosaurus aegyptiacus was discovered and recognized as a dinosaur – and it would be another century after that before we really started to learn anything about it.

1910s

The first fossils of Spinosauruswerediscovered in Egypt in the 1910s. With only a few fragments of its skeleton known it was an enigma right from the start, hinting at a large and very strange theropod dinosaur with crocodile-like teeth, an oddly-shaped lower jaw, and elongated neural spines on its vertebrae that seemed to be part of a huge sail.

A few possible extra fragments were found in the 1930s, but overall these few pieces were all that was known of Spinosaurus for a long time.

The fossils were kept in the Paleontological MuseuminMunich, Germany,a building that was severely damaged during a bombing raid in World War II. Many important specimens were destroyed, including Spinosaurus, and only the published drawings and descriptions of the bones remained.

So for the next several decades Spinosaurus remained a very poorly-understood mystery. During this period it was generally depicted as a generic “carnosaur”, often modeled on something like Megalosaurus, in the standard-for-the-time tripod pose and with a Dimetrodon-like sail on its back.

Interestinglya 1930s skeletal reconstructionshowsSpinosaurus with an unusually long torso and fairly short legs, details that are surprisingly modern despite the retro posture.

1990s

In the 1980s some partial snout bones from Niger were recognized as having similarities with the jaw of Spinosaurus. Around the same time the fairly complete skeleton of Baryonyx was discovered, and along with further spinosaurid discoveries in the mid-to-late 1990s a decent idea of what Spinosaurus might have looked like began to emerge.

It was reconstructed with a long kinked crocodilian-like snout, a ridged bony crest in front of its eyes, an S-curved neck, and large thumb claws on its hands – an interpretation that was heavily popularized by Jurassic Park III in the early 2000s, bringing this enigmatic dinosaur to public attention and portraying it as a fearsome super-predator bigger than Tyrannosaurus.

2020s

Despite attempts to locate more complete Spinosaurus remains, only fragments continued to be found, and it remained a frustratingly poorly-known species even into the early 2010s.

Finally, in 2014, almost a full century after it was first described and named, Spinosaurus started to reveal its secrets with the announcement of the discovery of the most complete skeleton so far, discovered in the Kem Kem fossil bedsinMorocco. Its body was still only partially represented, but it included skull fragments, part of a hand, a complete leg and pelvis, some sail spines, and several vertebrae from the neck, back, and tail.

And nobody was expecting what these pieces revealed.

It had a very long torso and proportionally short stumpy legs, and was reconstructed with a huge distinctive “M-shaped” sail on its back. Its feet had flat-bottomed claws and its “dewclaw” toe was enlarged into an extra weight-bearing digit – adaptations for spreading its weight over soft muddy ground, and suggesting its feet may also have been webbed. Initially it was also presented as possibly being quadrupedal, due to how far forward its center of mass seemed to be, reviving an odd idea from the late 20thcentury.

Along with its long crocodile-like head and conical teeth, this was interpreted as evidence it was a semiaquatic fish-eating swimming animal – potentially making it the first known semiaquatic non-avian dinosaur. Spinosaurids had been suggested to be specialized piscivores before, especially since Baryonyx had been found with fish scales in its stomach, but they were generally assumed to be more like modern grizzly bears, wading into water to hunt but not being habitual swimmers. Spinosaurus’ weird croco-duck proportions, however, seemed like they might be much more suited to watery habitats than to the land.

SinceSpinosaurus had become a popular dinosaur with the general public by that point, the discovery was big news – and a big controversy for a while. It was so bizarre that some paleontologists were skeptical of the radical new interpretation, wondering if the measurements of the skeleton were correct or if the short legs were even from the same individual or the same species as the rest of the bones.

After a while the new proportions were accepted as fairly accurate, and over the next few years attention turned to instead figuring out just how this animal worked and how aquatic it actually was. An earlier isotope analysis of its teeth supported a semiaquatic lifestyle similar to crocodiles and turtles, but a buoyancy study argued that it might not have been able to dive below the water suface and its sail made floating unstable – but also found that its center of mass was closer to its hips than previously calculated, suggesting it could walk bipedally after all.

Then in 2020 came another surprise: more of the tail of the new specimen had been found, and it was just as weird as the rest of Spinosaurus. Its tail was a huge vertically flattened paddle-like fin supported by long thin neural spines and chevrons, resembling a giant eel or newt more than a dinosaur and also giving some more weight to the idea that it was a swimmer.

Our modern view of Spinosaurus is still evolving, and likely to be full of even more surprises in the future as we discover more about this unique dinosaur. But we at least know it lived in what is now North Africa during the Late Cretaceous, about 99-93 million years ago, and whether it was a swimmer or wading generalist predator it was one of the largest known theropods to ever live, estimated to have reached around 16m long (~52ft).

While the “M-shaped” sail reconstruction has been popularized by the recent discoveries, the exact shape of this structure is still unknown. Like with other sailbacked animals it’s also not clear what it was for, with ideas including temperature regulation, visual display, supporting a fatty hump, and a potential hydrodynamic adaptation.

EDIT: And while I was working on this entry (late March 2022) I missed that another study had just come out with more anatomical support for swimming Spinosaurus!

———

Nix Illustration|Tumblr|Twitter|Patreon

Post link

Modern birds’ upper beaks are made up mostly from skull bones called the premaxilla, but the snouts of their earlier non-avian dinosaur ancestors were instead formed by large maxilla bones.

AndFalcatakely forsterae here had a very unusual combination of these features.

Living in Madagascar during the Late Cretaceous, about 70-66 million years ago, it was around 40cm long (1'4") and was part of a diverse lineage of Mesozoic birds known as enantiornitheans. These birds had claws on their wings and usually had toothy snouts instead of beaks, and many species also had ribbon-like display feathers on their tails instead of lift-generating fans.

Falcatakely had a long tall snout very similar in shape to a modern toucan, unlike any other known Mesozoic bird, with the surface texture of the bones indicating it was also covered by a keratinous beak. But despite this very “modern” face shape the bone arrangement was still much more similar to other enantiornitheans – there was a huge toothless maxilla making up the majority of the beak, with a small tooth-bearing premaxilla at the tip.

This suggests that there was more than one potential way for early birds to evolve modern-style beaks, and there may have been much more diversity in these animals’ facial structures than previously thought.

———

Nix Illustration|Tumblr|Twitter|Patreon

Post link

During the Early Carboniferous, around 330 million years ago, the region that is now the East Kirkton QuarryinScotland was located close to the equator, with a lush tropical climate and volcanic hot springs dotting the landscape. It preserves fossils of some of the earliest known fully terrestrial tetrapods, and a recent discovery shows how some of these animals were already experimenting with the shapes of their feet to better get around on land.

Termonerpeton makrydactylus is only known from a partial skeleton, and shows a mix of anatomical features that make identifying its exact evolutionary relationships rather difficult – but it was probably a very early reptilomorph, closer related to amniotes than to lissamphibians. It may also have been very closely related to the equally enigmatic EldeceeonandSilvanerpeton from the same region, but was almsot twice their size with a estimated total length of around 70cm (2'4").

It would have resembled a rather heavily-built lizard-like or salamander-like animal, with fairly stumpy legs and probably lacking claws on its digits. While it would have had spindle-shaped scales on its underside, and possibly small rounded scales along its sides and back, these were bony structures embedded in its skin and probably weren’t very visible externally in life.

ButTermonerpeton’s most surprising feature was its proportionally large feet with especially elongated fourth toes, which would have helped to extend its stride length for energy-efficient terrestrial locomotion and to stabilize its movement on unstable surfaces – a much more “advanced” amniote-like arrangement than expected in such an early reptilomorph, and convergently similar to to the foot shapes of some modern lizards. Its fourth toe was also unusually chunky, suggesting it may even have been bearing most of its weight on just that one digit when walking.

———

Nix Illustration|Tumblr|Twitter|Patreon

Post link

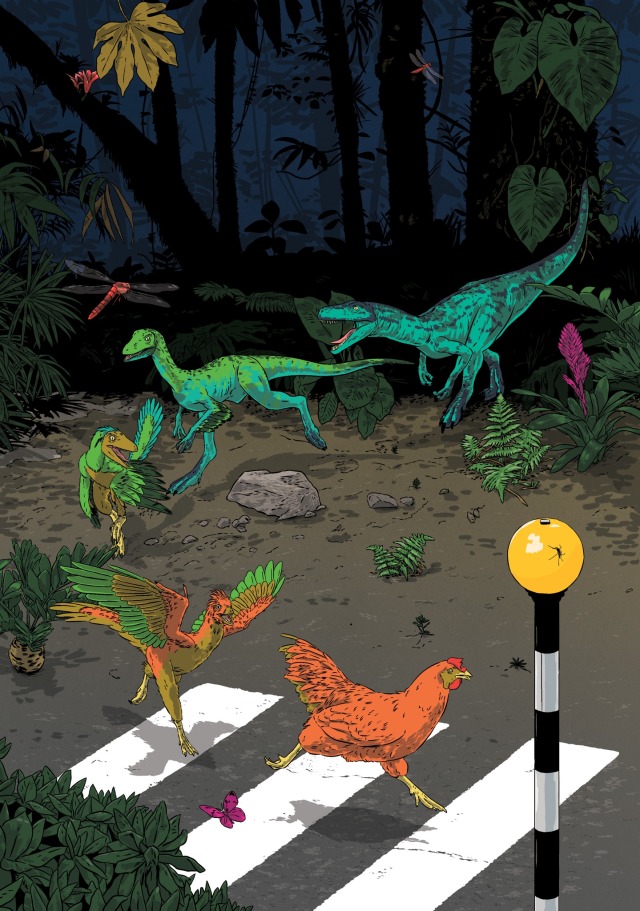

The Chickenosaurus Conundrum - a conceptual evolution illustration for the latest issue of Aquila Magazine!

Tentacles and Beaks of Cephalopods|December, 2015

Investigating the anatomical differences of cephalopod beaks and tentacles with regards to their diet.

Post link

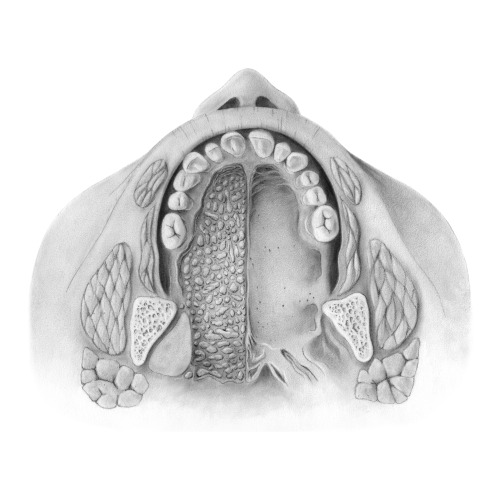

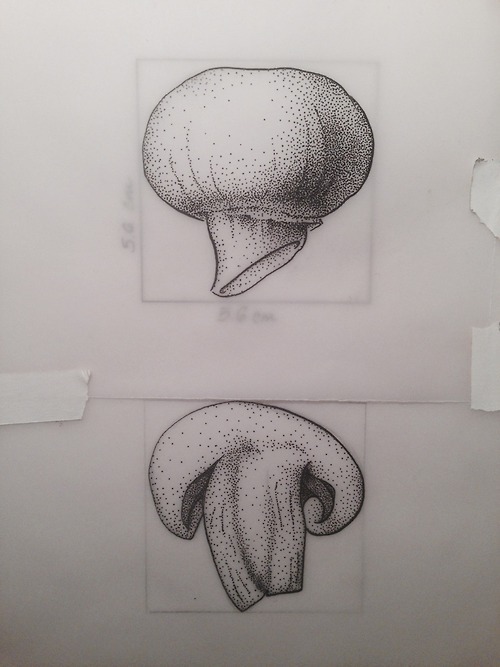

Palate, complete* | October, 2015

Carbon dust rendering of palate and associated muscles.

*specimen was missing teeth.

Post link

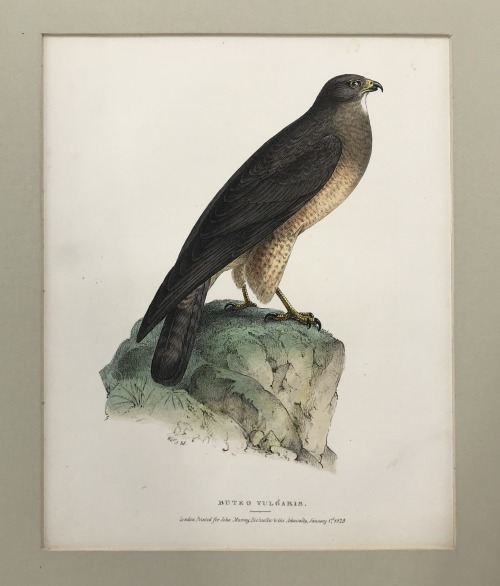

“Buteo Vulgaris”, William Swainson, circa 1831

Hand-colored engraving from “Fauna Boreali-Americana” published 1835

To help support the preservation of our collection click here.

Post link

“Crotophaga Rugirostra”, William Swainson, 1831

Hand-colored engraving from “Fauna Boreali-Americana”, 1835

To help support the preservation of our collection click here.

Post link

“Camass” (Camassia quamash), Winifred G. Stewart, circa 1935

Watercolor and pencil on paper

To help support the preservation of our collection click here.

Post link

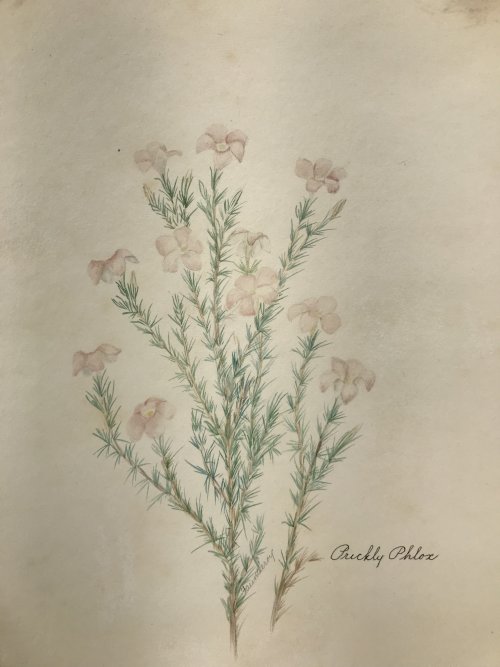

“Prickly Phlox” (Linanthus californicus), Sophie H. Fauntleroy, 1937

Watercolor and pencil on paper

To help support the preservation of our collection click here.

Post link

“Harlequin”, Winifred G. Stewart, circa 1935

Watercolor and pencil on paper

To help support the preservation of our collection click here.

Post link

“Tall Clarkia”, Ferdinand W. Haasis, 1948

Watercolor, gouache and pencil on paper

To help support the preservation of our collection click here.

Post link

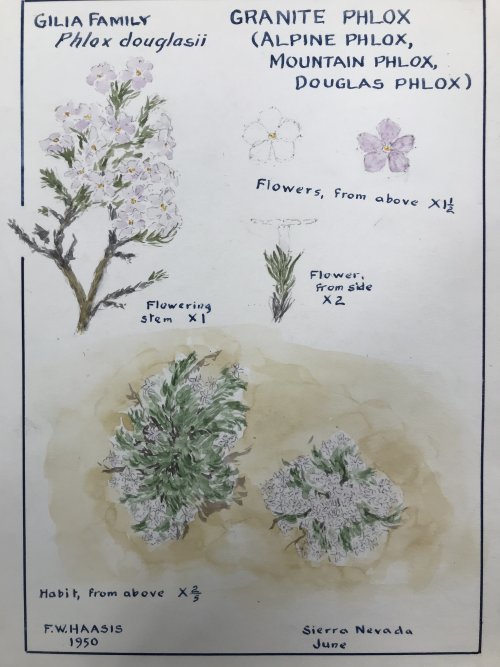

“Granite Phlox”, Ferdinand W. Haasis, 1950

Watercolor, gouache, pencil on paper

To help support the preservation of our collection click here.

Post link

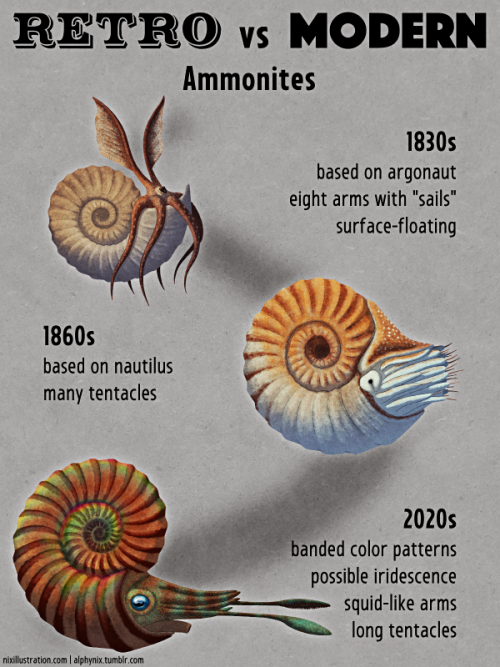

Retro vs Modern #17: Ammonites

Ammonites (or ammonoids) are highly distinctive and instantly recognizable fossils that have been found all around the world for thousands of years, and have been associated with a wide range of folkloric and mythologic interpretations – including snakestones,buffalo stones,shaligrams, and the horns of Ammon, with the latter eventually inspiring the scientific name for this group of ancient molluscs.

(Unlike the other entries in this series the reconstructions shown here are somewhat generalized ammonites. They’re not intended to depict a specific species, but the shell shape is mostly based on Asteroceras obtusum.)

1830s

It was only in the 1700s that ammonites began to be recognized as the remains of cephalopod shells, but the lack of soft part impressions made the rest of their anatomy a mystery. The very first known life reconstruction was part of the Duria Antiquior scene painted in 1830, but to modern eyes it probably isn’t immediately obvious as even being an ammonite, depicted as a strange little boat-like thing to the right of the battling ichthyosaur and plesiosaur.

Theargonaut octopus, or “paper nautilus”, was considered to be the closest living model for ammonites at the time due to superficial similarities in its “shell” shape, but these modern animals were also rather poorly understood. They were commonly inaccurately illustrated as floating around on the ocean surface using the expanded surfaces on two of their tentacles as “sails” – and so ammonites were initially reconstructed in the same way.

1860s

While increasing scientific knowledge of the chambered nautilus led to it being proposed as a better model for ammonites in the mid-1830s, the argonaut-style depictions continued for several decades.

Interestingly the earliest known non-argonaut reconstruction of an ammonite, in the first edition of La Terre Avant Le Déluge in 1863, actually showed a very squid-likeanimal inside an ammonite shell, with eight arms and two longer tentacles. But this was quickly “corrected” in later editions to a much more nautilus-like version with numerous cirri-like tentacles and a large hood.

The nautilus model for ammonites eventually became the standard by the end of the 19th century, although they continued to be reconstructed as surface-floaters. Bottom-dwelling ammonite interpretations were also popular for a while in the early 20th century, being shown as creeping animals with nautilus-like anatomy and numerous octopus-like tentacles, before open water active swimmers eventually became the standard representation.

2020s

During the 20th century opinions on the closest living relatives of ammonites began to shift away from nautiluses and towards the coleoids (squid, cuttlefish, and octopuses). The consensus by the 1990s was that both ammonites and coleoids had a common ancestry within the bactridids, and ammonites were considered to have likely had ten arms (at least ancestrally) and were probably much more squid-like after all.

Little was still actually known about these cephalopods’ soft parts, but some internal anatomy had at least been figured out by the early 21st century. Enigmatic fossils known as aptychi had been found preserved in position within ammonite shell cavities, and were initially thought to be an operculum closing off the shell against predators – but are currently considered to instead be part of the jaw apparatus along with a radula.

Tentative ink sac traces were also found in some specimens (although these are now disputed), and what were thought to be poorly-preserved digestive organs, but the actual external life appearance of ammonites was still basically unknown. By the mid-2010s the best guess reconstructionswerebased on muscle attachment sites that suggested the presence of a large squid-like siphon.

Possible evidence of banded color patterns were also sometimes found preserved on shells, while others showed iridescent patterns that might have been visible on the surface in life.

In the late 2010s the continued scarcity of ammonite soft tissue was potentially explained as being the same reason true squid fossils are so incredibly rare – their biochemistry may have simply been incompatible with the vast majority of preservation conditions.

But then something amazinghappened.

In early 2021 a “naked” ammonite missing its shell was described, preserving most of the body in exceptional detail – although frustratingly the arms were missing, giving no clarification to their possible number or arrangement. But then just a few months later another study focusing on mysterious hook-like structures in some ammonite fossils concluded that they came from the clubbed tips of a pair of long squid-like tentacles – the first direct evidence of any ammonite appendages!

Athird soft-tissue study at the end of the year added in some further confirmation that ammonites were much more coleoid-like than nautilus-like, with more evidence of a squid-style siphon, along with evidece of powerful muscles that retracted the ammonite’s body deep inside its shell cavity for protection.

Since ammonites existed for over 340 million years in a wide range of habitats and ecological roles, and came in a massive variety of shapes and sizes, it’s extremely likely that their soft anatomy was just as diverse as their shells – so there’s no single “one reconstruction fits all” for their life appearances. Still, at least we now have something less speculative to work with for restorations, even if it’s a bit generalized and composite, and now that we’re finally starting to find that elusive soft tissue there’s the potential for us to discover so much more about these iconic fossil animals.

———

Post link

Quick photo of the bird I had been working on for my Songbird drawing class. Hope to get a scan soon.

White-Crowned Sparrow (Zonotrichia leucophrys)

Post link