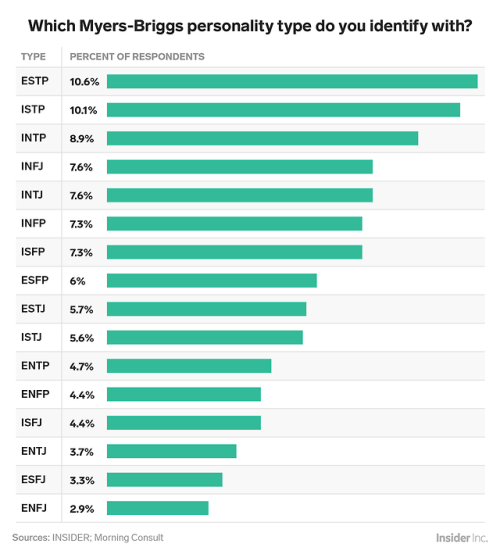

#personality

INTJ, INTP - Someone who can bring warmth to their coldness, light to their darkness, happiness to their depression, but also someone who understands how important the cold, the dark, and the depression is to them.

ENTJ, ESTJ - Someone who can challenge them, keep them entertained and interested yet keep them in their place.

INFP, ISFP - Someone who understands how complicated and simple they are, someone who doesn’t try to fix them or makes sense of them but just embraces them.

ENFP - Someone who takes everything they aspire to be and help them make it a reality, someone who makes them understand that dreams are great but accomplishments are better. Someone who acts like a mirror to them, makes sure they don’t go off the tracks yet, enjoys getting lost within them.

INFJ, ENFJ - Someone who makes them smile without hiding a frown within, someone who brings out the real them no matter how difficult

ESTP, ISTP, , ESFP - Someone who can ride with them to no place in specific yet always knows where to go when things get too overwhelming

ISTJ - Someone who makes them read beyond the words and helps them see beyond the facts and the rules, someone who adds paint to their canvas

ENTP - Someone who takes all the hate and highlights all the positives, someone who is able to truly talk to them and challenge them

ISFJ, ESFJ - Someone who doesn’t need help from them, someone who helps them find what they want for themselves

“yells by Renat-Renee-Ell”

☛http://bit.ly/1dG7rXS

New Editors’ Choice photo on 500px: Fashion

Post link

Be part of an important study on the genetics of sexual orientation

· Have you had your DNA analyzed by 23andMe or Ancestry?

· Are you 18 years or older?

If you answered YES to these questions, you are eligible to participate in a study on sexual orientation.

The purpose of this research study is to understand how genetics may influence people’s personalities and sexual orientation. If you take part in this online study, we will instruct you how to find your genetic data file on your 23andMe account and upload it to our secure website. We will also ask you to complete a series of questionnaires on your personality and sexual behavior.

Time required to complete the study should be about 15-25 minutes.

Anyone 18 years or older who has been sexually active and has had a 23andMe or Ancestry analysis is eligible to participate, regardless of sexual orientation.

Please follow this link to begin the study:

https://pennstate.qualtrics.com/SE/?SID=SV_e5Vi2kF7dFeGGr3

This study is being conducted by the Department of Anthropology at Penn State University, 409 Carpenter Building, University Park, PA.

Please contact the study coordinator Heather Self ([email protected]) or the principal investigator David Puts ([email protected]) for further information.

Be part of an important study on the genetics of sexual orientation

· Have you had your DNA analyzed by 23andMe or Ancestry?

· Are you 18 years or older?

If you answered YES to these questions, you are eligible to participate in a study on sexual orientation.

The purpose of this research study is to understand how genetics may influence people’s personalities and sexual orientation. If you take part in this online study, we will instruct you how to find your genetic data file on your 23andMe account and upload it to our secure website. We will also ask you to complete a series of questionnaires on your personality and sexual behavior.

Time required to complete the study should be about 15-25 minutes.

Anyone 18 years or older who has been sexually active and has had a 23andMe or Ancestry analysis is eligible to participate, regardless of sexual orientation.

Please follow this link to begin the study:

https://pennstate.qualtrics.com/SE/?SID=SV_e5Vi2kF7dFeGGr3

This study is being conducted by the Department of Anthropology at Penn State University, 409 Carpenter Building, University Park, PA.

Please contact the study coordinator Heather Self ([email protected]) or the principal investigator David Puts ([email protected]) for further information.

Be part of an important study on the genetics of sexual orientation

· Have you had your DNA analyzed by 23andMe or Ancestry?

· Are you 18 years or older?

If you answered YES to these questions, you are eligible to participate in a study on sexual orientation.

The purpose of this research study is to understand how genetics may influence people’s personalities and sexual orientation. If you take part in this online study, we will instruct you how to find your genetic data file on your 23andMe account and upload it to our secure website. We will also ask you to complete a series of questionnaires on your personality and sexual behavior.

Time required to complete the study should be about 15-25 minutes.

Anyone 18 years or older who has been sexually active and has had a 23andMe or Ancestry analysis is eligible to participate, regardless of sexual orientation.

Please follow this link to begin the study:

https://pennstate.qualtrics.com/SE/?SID=SV_e5Vi2kF7dFeGGr3

This study is being conducted by the Department of Anthropology at Penn State University, 409 Carpenter Building, University Park, PA.

Please contact the study coordinator Heather Self ([email protected]) or the principal investigator David Puts ([email protected]) for further information.

Personality is the mostimportant thing about your character.

So, whenever I see character sheets, most people just put a little paragraph for that section. If you’re struggling and don’t know what your character should say or do, what decisions they should make, I guaranteeyou that this is the problem.

You know your character’s name, age, race, sexuality, height, weight, eye color, hair color, their parents’ and siblings’ names. But these are not the things that truly matter about them.

Traits:

- pick traits that don’t necessarily go together. For example, someone who is controlling, aggressive and vain can also be generous, sensitive and soft-spoken. Characters need to have at least one flaw that reallyimpacts how they interact with others. Positive traits can work as flaws, too. It is advised that you pick at least ten traits

- people are complex, full of contradictions, and please forgive me if this makes anyone uncomfortable, but even bullies can be “nice” people. Anyonecan be a “bad” person, even someone who is polite, kind, helpful or timid can also be narcissistic, annoying, inconsiderate and a liar. People are notjust “evil” or “good”

Beliefs:

- ideas or thoughts that your character has or thinks about the world, society, others or themselves, even without proof or evidence, or which may or may not be true. Beliefs can contradict their values, motives, self-image, etc. For example, the belief that they are an awesome and responsible person when their traits are lazy, irresponsible and shallow. Their self-image and any beliefs they have about themselves may or may not be similar/the same. They might have a poor self-image, but still believe they’re better than everybody else

Values:

- what your character thinks is important. Usually influenced by beliefs, their self-image, their history, etc. Some values may contradict their beliefs, wants, traits, or even other values. For example, your character may value being respect, but one of their traits is disrespectful. It is advised you list at least two values, and know which one they value more. For example, your character values justice and family. Their sister tells them she just stole $200 from her teacher’s wallet. Do they tell on her, or do they let her keep the money: justice, or family? Either way, your character probably has some negative feelings, guilt, anger, etc., over betraying their other value

Motives:

- what your character wants. It can be abstract or something tangible. For example, wanting to be adored or wanting that job to pay for their father’s medication. Motives can contradict their beliefs, traits, values, behavior, or even other motives. For example, your character may want to be a good person, but their traits are selfish, manipulative, and narcissistic. Motives can be long term or short term. Everyonehas wants, whether they realize it or not. You can write “they don’t know what they want,” but youshould know. It is advised that you list at least one abstract want

Recurring Feelings:

- feelings that they have throughout most of their life. If you put them down as a trait, it is likely they are also recurring feelings. For example, depressed, lonely, happy, etc.

Self Image:

- what the character thinks of themselves: their self-esteem. Some character are proud of themselves, others are ashamed of themselves, etc. They may think they are not good enough, or think they are the smartest person in the world. Their self-image can contradict their beliefs, traits, values, behavior, motives, etc. For example, if their self-image is poor, they can still be a cheerful or optimistic person. If they have a positive self-image, they can still be a depressed or negative person. How they picture themselves may or may not be true: maybe they think they’re a horrible person, when they are, in fact, very considerate, helpful, kind, generous, patient, etc. They still have flaws, but flaws don’t necessarily make you a terrible person

Behavior:

- how the character’s traits, values, beliefs, self-image, etc., are outwardly displayed: how they act. For example, two characters may have the trait “angry” but they all probably express it differently. One character may be quiet and want to be left alone when they are angry, the other could become verbally aggressive. If your character is a liar, do they pause before lying, or do they suddenly speak very carefully when they normally don’t? Someone who is inconsiderate may have issues with boundaries or eat the last piece of pizza in the fridge when they knew it wasn’t theirs. Behavior is extremely important and it is advised you think long and hard about your character’s actions and what exactly it shows about them

Demeanor:

- their general mood and disposition. Maybe they’re usually quiet, cheerful, moody, or irritable, etc.

Posture:

- a secondary part of your character’s personality: not as important as everything else. It is advised you fill this out after. Posture is how the character carries themselves. For example, perhaps they swing their arms and keep their shoulders back while they walk, which seems to be the posture of a confident person, so when they sit, their legs are probably open. Another character may slump and have their arms folded when they’re sitting, and when they’re walking, perhaps they drag their feet and look at the ground

Speech Pattern:

- a secondary part of your character’s personality: not as important as everything else. It is advised you fill this out after. Speech patterns can be words that your character uses frequently, if they speak clearly, what sort of grammar they use, if they have a wide vocabulary, a small vocabulary, if it’s sophisticated, crude, stammering, repeating themselves, etc. I personally don’t have a very wide vocabulary, if you could tell

Hobbies:

- a secondary part of your character’s personality: not as important as everything else. It is advised you fill this out after. Hobbies can include things like drawing, writing, playing an instrument, collecting rocks, collecting tea cups, etc.

Quirks:

- a secondary part of your character’s personality, not as important as everything else. It is advised you fill this out after. Quirks are behaviors that are unique to your character. For example, I personally always put my socks on inside out and check the ceiling for spiders a few times a day

Likes:

- a secondary part of your character’s personality, not as important as everything else. It is advised you fill this out after. Likes and dislikes are usually connected to the rest of their personality, but not necessarily. For example, if your character likes to do other people’s homework, maybe it’s because they want to be appreciated

Dislikes:

- a secondary part of your character’s personality, not as important as everything else. It is advised you fill this out after. Likes and dislikes can also contradict the rest of their personality. For example, maybe one of your character’s traits is dishonest, but they dislike liars

History:

- your character’s past that has key events that influence and shape their beliefs, values, behavior, wants, self-image, etc. Events written down should imply or explain why they are the way they are. For example, if your character is distrustful, maybe they were lied to a lot by their parents when they were a child. Maybe they were in a relationship for twenty years and found out their partner was cheating on them the whole time. If their motive/want is to have positive attention, maybe their parents just didn’t praise them enough and focused too much on the negative

On Mental and Physical Disabilities or Illnesses

- if your character experienced a trauma, it needs to have an affect on your character. Maybe they became more angry or impatient or critical of others. Maybe their beliefs on people changed to become “even bullies can be ‘nice’ people: anyone can be a ‘bad’ person”

- people are nottheir illness or disability: it should notbe their defining trait. I have health anxiety, but I’m still idealistic, lazy, considerate, impatient and occasionally spiteful; I still want to become an author; I still believe that people are generally good; I still value doing what make me feel comfortable; I still have a positive self-image; I’m still a person. You should fill out your character’s personality at least half-way before you even touch on the possibility of your character having a disability or illness

Generally everything about your character should connect, but hey, even twins that grew up in the same exact household have different personalities; they value different things, have different beliefs. Maybe one of them watched a movie that had a huge impact on them.

Noteverythingneeds to be explained. Someone can be picky or fussy ever since they were little for no reason at all. Someone can be a negative person even if they grew up in a happy home.

I believe this is a thought out layout for making well-rounded OCs, antagonists and protagonists, whether they’re being created for a roleplay or for a book. This layout is also helpful for studying Canon Characters if you’re looking to accurately roleplay as them or write them in fanfiction or whatever.

I’m really excited to post this, so hopefully I didn’t miss anything important…

If you have any questions, feel free to send a message.

- Chick

Snape knowing unsupported flight being revealed then dismissed in such a nonchalant way is hilarious to me like oh yeah Snape can fly without a broom, btw it’s an extremely rare, unprecedented skill previously thought to be impossible and only ever used by one other person, the Dark Lord himself, but anyway-

No seriously I can’t stop thinking about Snape being the half blood prince. Him stealing away a little nickname for himself, perhaps to bolster him when life gave him its ass to kiss. A secret little bit of pride he could hold on to when he was constantly reminded of how he lacked. But Snape’s status as Prince wasn’t just a moniker he adopted, a nickname he gave himself, it was something he simply was, something he was born as. His birthright/claim to Prince is validated not by the characters acknowledging him as such but by the text itself, with chapters centring him referring to him as Prince e.g. “The Flight of the Prince” or “The Prince’s Tale.” Of all the characters, the legions of aristocratic, pure blood, upper crust characters crawling around this universe, the Prince is this strange little man who lived a wretched life, a life defined by cruelty and bitterness but also bravery and selflessness, a Prince from humblest origins.

There’s something about the title “The Prince’s Tale” that really gets me. It sounds like the legend of some historical or mythical figure–someone fantastical, larger than life, a knight in shining armor–but then you read it and it’s the story of a broken man. And really just that, a man–not this foreboding, almost inhuman figure we thought Snape was for so long. “The Prince’s Tale” is the chapter that peels back those layers of mystery and legend surrounding him, removes that forbidding exterior and reveals the child who wished for a better life–perhaps wished to be that Prince–and just wanted love–that core aspect of Snape’s being that pulled him out of the darkness in the end. It’s the chapter where we finally see him(almost the culmination of his final “Look at me”)–and the book validates that, in all this sorrow and heartbreak and humanity, he is the Prince.

I will always find it fascinating that young Severus didn’t just call himself The Prince. I mean, we have pretentious allusions to Machiavelli right there. But no, he (or JKR) specifically chose the Half-Blood Prince, despite it being the sort of nickname you’d expect his enemies to throw at him, to mock him with, signifying “not good enough” and “impure.” Not only does it not ignore his status as a half-blood, it emphasizes it - i.e., he’s half-Muggle, something we’re led to assume he rejects as a follower of pureblood ideology. Yet he claims it as part of his secret, daydreaming identity as a teenager. It’s his superhero title. He projects onto both sides of his heritage, unites them in one name, and the implication is that he finds it empowering, romanticized the way adolescent self-creation often is.

Yet we never see it reflected in Snape’s day-to-day behavior. It almost seems out of character for him to recognize his Muggle “half.” So what did it mean to him? How did he imagine himself reconciling - living up to - both sides of the Half-Blood Prince?

I imagine vulnera sanetur to be just like the healing song in the Rapunzel disney movie

It’s beyond me why the HP fandom lets it slide that our man Snape canonically made up a healingsong like a goddamn Disney princess, like… he really did that

Yeah. There’s all these weird headcanons about how he would hate teaching the Slytherins dancing for the Yule ball. Or even worse, be all awkward about it. Which??? The man is a poet and a singer, I don’t know why he’d be uncomfortable dancing. He’d treat it the way he treats any other class, make an elaborate monologue and look impressive.

Protagonist (ENFJ)

ENFJs are natural-born leaders, full of passion and charisma. Forming around two percent of the population, they are oftentimes our politicians, our coaches and our teachers, reaching out and inspiring others to achieve and to do good in the world. With a natural confidence that begets influence, ENFJs take a great deal of pride and joy in guiding others to work together to improve themselves and their community.

Firm Believers in the People

People are drawn to strong personalities, and ENFJs radiate authenticity, concern and altruism, unafraid to stand up and speak when they feel something needs to be said. They find it natural and easy to communicate with others, especially in person, and their Intuitive (N) trait helps people with the ENFJ personality type to reach every mind, be it through facts and logic or raw emotion. ENFJs easily see people’s motivations and seemingly disconnected events, and are able to bring these ideas together and communicate them as a common goal with an eloquence that is nothing short of mesmerizing.

The interest ENFJs have in others is genuine, almost to a fault – when they believe in someone, they can become too involved in the other person’s problems, place too much trust in them. Luckily, this trust tends to be a self-fulfilling prophesy, as ENFJs’ altruism and authenticity inspire those they care about to become better themselves. But if they aren’t careful, they can overextend their optimism, sometimes pushing others further than they’re ready or willing to go.

ENFJs are vulnerable to another snare as well: they have a tremendous capacity for reflecting on and analyzing their own feelings, but if they get too caught up in another person’s plight, they can develop a sort of emotional hypochondria, seeing other people’s problems in themselves, trying to fix something in themselves that isn’t wrong. If they get to a point where they are held back by limitations someone else is experiencing, it can hinder ENFJs’ ability to see past the dilemma and be of any help at all. When this happens, it’s important for ENFJs to pull back and use that self-reflection to distinguish between what they really feel, and what is a separate issue that needs to be looked at from another perspective.

The Struggle Ought Not to Deter Us From the Support of a Cause We Believe to Be Just

ENFJs are genuine, caring people who talk the talk and walk the walk, and nothing makes them happier than leading the charge, uniting and motivating their team with infectious enthusiasm.

People with the ENFJ personality type are passionate altruists, sometimes even to a fault, and they are unlikely to be afraid to take the slings and arrows while standing up for the people and ideas they believe in. It is no wonder that many famous ENFJs are US Presidents – this personality type wants to lead the way to a brighter future, whether it’s by leading a nation to prosperity, or leading their little league softball team to a hard-fought victory.

ENFJ Strengths

- Tolerant – ENFJs are true team players, and they recognize that that means listening to other peoples’ opinions, even when they contradict their own. They admit they don’t have all the answers, and are often receptive to dissent, so long as it remains constructive.

- Reliable – The one thing that galls ENFJs the most is the idea of letting down a person or cause they believe in. If it’s possible, ENFJs can always be counted on to see it through.

- Charismatic – Charm and popularity are qualities ENFJs have in spades. They instinctively know how to capture an audience, and pick up on mood and motivation in ways that allow them to communicate with reason, emotion, passion, restraint – whatever the situation calls for. Talented imitators, ENFJs are able to shift their tone and manner to reflect the needs of the audience, while still maintaining their own voice.

- Altruistic – Uniting these qualities is ENFJs’ unyielding desire to do good in and for their communities, be it in their own home or the global stage. Warm and selfless, ENFJs genuinely believe that if they can just bring people together, they can do a world of good.

- Natural Leaders – More than seeking authority themselves, ENFJs often end up in leadership roles at the request of others, cheered on by the many admirers of their strong personality and positive vision.

ENFJ Weaknesses

- Overly Idealistic – People with the ENFJ personality type can be caught off guard as they find that, through circumstance or nature, or simple misunderstanding, people fight against them and defy the principles they’ve adopted, however well-intentioned they may be. They are more likely to feel pity for this opposition than anger, and can earn a reputation of naïveté.

- Too Selfless – ENFJs can bury themselves in their hopeful promises, feeling others’ problems as their own and striving hard to meet their word. If they aren’t careful, they can spread themselves too thin, and be left unable to help anyone.

- Too Sensitive – While receptive to criticism, seeing it as a tool for leading a better team, it’s easy for ENFJs to take it a little too much to heart. Their sensitivity to others means that ENFJs sometimes feel problems that aren’t their own and try to fix things they can’t fix, worrying if they are doing enough.

- Fluctuating Self-Esteem – ENFJs define their self-esteem by whether they are able to live up to their ideals, and sometimes ask for criticism more out of insecurity than out of confidence, always wondering what they could do better. If they fail to meet a goal or to help someone they said they’d help, their self-confidence will undoubtedly plummet.

- Struggle to Make Tough Decisions – If caught between a rock and a hard place, ENFJs can be stricken with paralysis, imagining all the consequences of their actions, especially if those consequences are humanitarian.

ENFJ RELATIONSHIPS

People who share the ENFJ personality type feel most at home when they are in a relationship, and few types are more eager to establish a loving commitment with their chosen partners. ENFJs take dating and relationships seriously, selecting partners with an eye towards the long haul, rather than the more casual approach that might be expected from some Explorer (SP) types. There’s really no greater joy for ENFJs than to help along the goals of someone they care about, and the interweaving of lives that a committed relationship represents is the perfect opportunity to do just that.

I’m a Slow Walker, but I Never Walk Back

Even in the dating phase, people with the ENFJ personality type are ready to show their commitment by taking the time and effort to establish themselves as dependable, trustworthy partners.

Their Intuitive (N) trait helps them to keep up with the rapidly shifting moods that are common early in relationships, but ENFJs will still rely on conversations about their mutual feelings, checking the pulse of the relationship by asking how things are, and if there’s anything else they can do. While this can help to keep conflict, which ENFJs abhor, to a minimum, they also risk being overbearing or needy – ENFJs should keep in mind that sometimes the only thing that’s wrong is being asked what’s wrong too often.

ENFJs don’t need much to be happy, just to know that their partner is happy, and for their partner to express that happiness through visible affection. Making others’ goals come to fruition is often the chiefest concern of ENFJs, and they will spare no effort in helping their partner to live the dream. If they aren’t careful though, ENFJs’ quest for their partners’ satisfaction can leave them neglecting their own needs, and it’s important for them to remember to express those needs on occasion, especially early on.

You Cannot Escape the Responsibility of Tomorrow by Evading It Today

ENFJs’ tendency to avoid any kind of conflict, sometimes even sacrificing their own principles to keep the peace, can lead to long-term problems if these efforts never fully resolve the underlying issues that they mask. On the other hand, people with the ENFJ personality type can sometimes be too preemptive in resolving their conflicts, asking for criticisms and suggestions in ways that convey neediness or insecurity. ENFJs invest their emotions wholly in their relationships, and are sometimes so eager to please that it actually undermines the relationship – this can lead to resentment, and even the failure of the relationship. When this happens, ENFJs experience strong senses of guilt and betrayal, as they see all their efforts slip away.

If potential partners appreciate these qualities though, and make an effort themselves to look after the needs of their ENFJ partners, they will enjoy long, happy, passionate relationships. ENFJs are known to be dependable lovers, perhaps more interested in routine and stability than spontaneity in their sex lives, but always dedicated to the selfless satisfaction of their partners. Ultimately, ENFJ personality types believe that the only true happiness is mutual happiness, and that’s the stuff successful relationships are made of.

ENFJ FRIENDS

When it comes to friendships, ENFJs are anything but passive. While some personality types may accept the circumstantial highs and lows of friendship, their feelings waxing and waning with the times, ENFJs will put active effort into maintaining these connections, viewing them as substantial and important, not something to let slip away through laziness or inattention.

This philosophy of genuine connection is core to the ENFJ personality type, and while it is visible in the workplace and in romance, it is clearest in the breadth and depth of ENFJ friendships.

All My Life I Have Tried to Pluck a Thistle and Plant a Flower Wherever the Flower Would Grow…

People with the ENFJ personality type take genuine pleasure in getting to know other people, and have no trouble talking with people of all types and modes of thought. Even in disagreement, other perspectives are fascinating to ENFJs – though like most people, they connect best with individuals who share their principles and ideals, and Diplomats (NF) and Analysts (NT) are best able to explore ENFJs’ viewpoints with them, which are simply too idealistic for most. It is with these closest friends that ENFJs will truly open up, keeping their many other connections in a realm of lighthearted but genuine support and encouragement.

Others truly value their ENFJ friends, appreciating the warmth, kindness, and sincere optimism and cheer they bring to the table. ENFJs want to be the best friends possible, and it shows in how they work to find out not just the superficial interests of their friends, but their strengths, passions, hopes and dreams. Nothing makes ENFJs happier than to see the people they care about do well, and they are more than happy to take their own time and energy to help make it happen.

We Should Be Too Big to Take Offense, and Too Noble to Give It

While ENFJs enjoy lending this helping hand, other personality types may simply not have the energy or drive to keep up with it – creating further strain, people with the ENFJ personality type can become offended if their efforts aren’t reciprocated when the opportunity arises. Ultimately, ENFJs’ give and take can become stifling to types who are more interested in the moment than the future, or who simply have Identities that rest firmly on the Assertive side, making them content with who they are and uninterested in the sort of self-improvement and goal-setting that ENFJs hold so dear.

When this happens ENFJ personalities can be critical, if they believe it necessary. While usually tactful and often helpful, if their friend is already annoyed by ENFJs’ attempts to push them forward, it can simply cause them to dig in their heels further. ENFJs should try to avoid taking this personally when it happens, and relax their inflexibility into an occasional “live and let live” attitude.

Ultimately though, ENFJs will find that their excitement and unyielding optimism will yield them many satisfying relationships with people who appreciate and share their vision and authenticity. The joy ENFJs take in moving things forward means that there is always a sense of purpose behind their friendships, creating bonds that are not easily shaken.

ENFJ PARENTS

As natural leaders, ENFJs make excellent parents, striving to strike a balance between being encouraging and supportive friends to their children, while also working to instil strong values and a sense of personal responsibility. If there’s one strong trend with the ENFJ personality type, it’s that they are a bedrock of empathetic support, not bullheadedly telling people what they ought to do, but helping them to explore their options and encouraging them to follow their hearts.

ENFJ parents will encourage their children to explore and grow, recognizing and appreciating the individuality of the people they bring into this world and help to raise.

Whatever You Are, Be a Good One

ENFJ parents take pride in nurturing and inspiring strong values, and they take care to ensure that the basis for these values comes from understanding, not blind obedience. Whatever their children need in order to learn and grow, ENFJ parents give the time and energy necessary to provide it. While in their weaker moments they may succumb to more manipulative behavior, ENFJs mostly rely on their charm and idealism to make sure their children take these lessons to heart.

Owing to their aversion to conflict, ENFJ parents strive to ensure that their homes provide a safe and conflict-free environment. While they can deliver criticism, it’s not ENFJs’ strong suit, and laying down the occasionally necessary discipline won’t come naturally. But, people with the ENFJ personality type have high standards for their children, encouraging them to be the best they can be, and when these confrontations do happen, they try to frame the lessons as archetypes, moral constants in life which they hope their children will embrace.

As their children enter adolescence, they begin to truly make their own decisions, sometimes contrary to what their parents want – while ENFJs will do their best to meet this with grace and humor, they can feel hurt, and even unloved, in the face of this rebellion. ENFJs are sensitive, and if their child goes so far as to launch into criticisms, they may become truly upset, digging in their heels and locking horns.

All That I Am, or Hope to Be, I Owe to My Angel Mother

Luckily, these occasions will likely be rare. ENFJs’ intuition gives them a talent for understanding, and regardless of the heat of the moment, their children will move on, remembering the genuine warmth, care, love and encouragement they’ve always received from their ENFJ parents. They grow up feeling the lessons that have been woven into the fabric of their character, and recognize that they are the better for their parents’ efforts.

ENFJ CAREERS

When it comes to finding a career, people with the ENFJ personality type cast their eyes towards anything that lets them do what they love most – helping other people! Lucky for them, people like being helped, and are even willing to pay for it, which means that ENFJs are rarely wanting for inspiration and opportunity in their search for meaningful work.

Don’t Worry When You Are Not Recognized, but Strive to Be Worthy of Recognition

ENFJs take a genuine interest in other people, approaching them with warm sociability and a helpful earnestness that rarely goes unnoticed. Altruistic careers like social and religious work, teaching, counseling, and advising of all sorts are popular avenues, giving people with the ENFJ personality type a chance to help others learn, grow, and become more independent. This attitude, alongside their social skills, emotional intelligence and tendency to be “that person who knows everybody”, can be adapted to quite a range of other careers as well, making ENFJs natural HR administrators, event coordinators, and politicians – anything that helps a community or organization to operate more smoothly.

To top it all off, ENFJs are able to express themselves both creatively and honestly, allowing them to approach positions as sales representatives and advertising consultants from a certain idealistic perspective, intuitively picking up on the needs and wants of their customers, and working to make them happier. However, ENFJs need to make sure they get to focus on people, not systems and spreadsheets, and they are unlikely to have the stomach for making the sort of decisions required in corporate governance positions – they will feel haunted, knowing that their decision cost someone their job, or that their product cost someone their life.

Having a preference for Intuition (N) over Observation (S) also means that careers demanding exceptional situational awareness, such as law enforcement, military service, and emergency response, will cause ENFJs to burn out quickly. While great at organizing willing parties and winning over skeptics, in dangerous situations ENFJs just won’t be able to maintain the sort of focus on their immediate physical surroundings that they inevitably demand of themselves hour after hour, day after day.

Always Bear in Mind That Your Own Resolution to Succeed Is More Important Than Any Other

It makes a great deal more sense for ENFJs to be the force keeping these vital services organized and running well, taking their long-term views, people skills and idealism, and using them to shape the situation on the ground, while more physical personality types manage the moment-to-moment crises. People with the ENFJ personality type are always up for a good challenge – and nothing thrills them quite like helping others. But while willing to train the necessary skills, ENFJs will always show an underlying preference for the sort of help that draws a positive long-term trend, that effects change that really sticks.

At the heart of it, ENFJs need to see how the story ends, to feel and experience the gratitude and appreciation of the people they’ve helped in order to be happy.

Careers operating behind enemy lines and arriving at the scene of the crime too late to help will simply weigh on ENFJs’ sensitive hearts and minds, especially if criticized despite their efforts. On the other hand, ENFJs are a driven, versatile group, and that same vision that pulls them towards administration and politics can help them focus through the stress of the moment, knowing that each second of effort contributes to something bigger than themselves.

ENFJ IN THE WORKPLACE

People with the ENFJ personality type are intelligent, warm, idealistic, charismatic, creative, social… With this wind at their backs, ENFJs are able to thrive in many diverse roles, at any level of seniority. Moreover, they are simply likeable people, and this quality propels them to success wherever they have a chance to work with others.

ENFJ Subordinates

As subordinates, ENFJs will often underestimate themselves – nevertheless, they quickly make an impression on their managers. Quick learners and excellent multitaskers, people with the ENFJ personality type are able to take on multiple responsibilities with competence and good cheer. ENFJs are hardworking, reliable and eager to help – but this can all be a double-edged sword, as some managers will take advantage of ENFJs’ excellent quality of character by making too many requests and overburdening their ENFJ subordinates with extra work. ENFJs are conflict-averse and try to avoid unnecessary criticism, and in all likelihood will accept these extra tasks in an attempt to maintain a positive impression and frictionless environment.

ENFJ Colleagues

As colleagues, ENFJs’ desire to assist and cooperate is even more evident as they draw their coworkers into teams where everyone can feel comfortable expressing their opinions and suggestions, working together to develop win-win situations that get the job done. ENFJs’ tolerance, open-mindedness and easy sociability make it easy for them to relate to their colleagues, but also make it perhaps a little too easy for their colleagues to shift their problems onto ENFJs’ plates. Being Diplomats (NF), people with the ENFJ personality type are sensitive to the needs of others, and their role as a social nexus means that problems inevitably find their way to ENFJs’ doorsteps, where colleagues will find a willing, if overburdened, associate.

ENFJ Managers

While perfectly capable as subordinates and colleagues, ENFJs’ true calling, where their capacity for insightful and inspiring communication and sensitivity to the needs of others really shows, is in managing teams. As managers, ENFJs combine their skill in recognizing individual motivations with their natural charisma to not only push their teams and projects forward, but to make their teams want to push forward. They may sometimes stoop to manipulation, the alternative often being a more direct confrontation, but ENFJs’ end goal is always to get done what they set out to do in a way that leaves everyone involved satisfied with their roles and the results they achieved together.

CONCLUSION

Few personality types are as inspiring and charismatic as ENFJs. Their idealism and vision allow ENFJs to overcome many challenging obstacles, more often than not brightening the lives of those around them. ENFJs’ imagination is invaluable in many areas, including their own personal growth.

Yet ENFJs can be easily tripped up in areas where idealism and altruism are more of a liability than an asset. Whether it is finding (or keeping) a partner, staying calm under pressure, reaching dazzling heights on the career ladder or making difficult decisions, ENFJs need to put in a conscious effort to develop their weaker traits and additional skills.

What you have read so far is just an introduction into the complex concept that is the ENFJ personality type. You may have muttered to yourself, “wow, this is so accurate it’s a little creepy” or “finally, someone understands me!” You may have even asked “how do they know more about me than the people I’m closest to?”

This is not a trick. You felt understood because you were. We’ve studied how ENFJs think and what they need to reach their full potential. And no, we did not spy on you – many of the challenges you’ve faced and will face in the future have been overcome by other ENFJs. You simply need to learn how they succeeded.

But in order to do that, you need to have a plan, a personal roadmap. The best car in the world will not take you to the right place if you do not know where you want to go. We have told you how ENFJs tend to behave in certain circumstances and what their key strengths and weaknesses are. Now we need to go much deeper into your personality type and answer “why?”, “how?” and “what if?”

This knowledge is only the beginning of a lifelong journey. Are you ready to learn why ENFJs act in the way they do? What motivates and inspires you? What you are afraid of and what you secretly dream about? How you can unlock your true, exceptional potential?

Our premium profiles provide a roadmap towards a happier, more successful, and more versatile YOU! They are not for everyone though – you need to be willing and able to challenge yourself, to go beyond the obvious, to imagine and follow your own path instead of just going with the flow. If you want to take the reins into your own hands, we are here to help you.

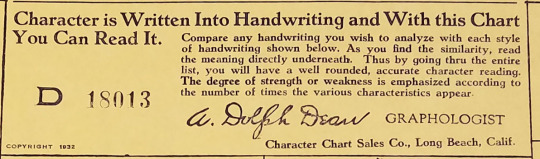

Your Character is Written into Your Handwriting

We stumbled across these bright, and interesting charts calling forth from a box of equity case files. As with most things archival, looking into the history of these records, opened a fabulous rabbit hole that we were happy to travel down!

Graphology! That is the name of the game. Graphology is the self-proclaimed science which analyzes handwriting for personality traits. These particular charts were part of two court cases in which A. Dolph Dean, Graphologist was asserting his 1932 copyright for his chart, “Character is Written into Handwriting and With this Chart You Can Read It.”

A. Dolph Dean, C. Ellsworth Bower, and Professor John W. Burke of the Personality Analysis Guild were not the only promoters of the value of graphology (at the rates of 10-50 cents per review - $1.50-$8.00 in today’s money). California newspapers were in the game as well:

The Los Angeles Times’ Muriel Stafford, provided graphological assistance with love matches, and to determine levels of culture and taste, in addition to analyzing the handwriting of everyone from George Washington (declared to be a stubborn humorist) to Bing Crosby (declared to be magnetic and easy-going). At one point, she proclaimed Los Angeles a warm-hearted, affectionate, generous city based on the handwriting of the Angelinos who wrote to her.

Post link

“Choose the free and playful solitude that gives you the right to remain good in some sense.”

—F. Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil, §25 (edited excerpt).

Hello ghosts of readers past! My blog, you might have noticed, is very dead. I’ve been busy with school, but I’m getting to the point where I can conduct research with real standards and real methods.

I’m currently working on a pet project, on music preference and personality. I’d love for you to complete this survey:

https://www.psytoolkit.org/cgi-bin/psy2.5.2/survey?s=RyqAj

And I will try to post the results once I get them. If they’re interesting, it may turn into a full study.

I might also try to write a post over the Xmas break about one of the personality measures used in the survey – the Affective Neuroscience Personality Scales – and the theory behind it.

Cheers!

Can we cleanly define a personality construct? This essay explores how that might not be possible, and why.

Multiple determination

Lou Gehrig’s disease (which afflicted Stephen Hawking and was the subject of the ALS “ice bucket challenge”) is a disease of the motor neurons that control voluntary movement, resulting in total body paralysis, eventually affecting the facial and respiratory systems. The cause in unknown in most cases, and there is no cure. Part of the reason for this is that there is no one way in which ALS develops. ‘Degeneration of motor neurons’ is something we can understand at the relatively macroscopic level of cells and circuits, however there are innumerable ways in which genetic mutations or other afflictions can result in this degeneration. We simply don’t have a handle on the hundreds or thousands of cell processes that can go wrong. In addition, a single malfunction might not be enough to cause a case of ALS; it might take a dozen errors operating in concert.

There is no one-to-one correspondence between a biological process and the symptoms of Lou Gehrig’s disease. A similar problem is encountered in the field of psychiatry. For the last few decades, biologists have tried to track down the genes responsible for disorders such as schizophrenia (operating under the hypothesis that these disorders are fundamentally biochemical). However, what they have found is a massive number of genes linking to schizophrenia at a statistically significant level, but each contributing only a fraction of a percent towards the likelihood of psychosis. The resulting hypothesis is that schizophrenia is a polygenic disorder. Like ALS (and a host of other conditions), it takes many processes acting in concert to result in the disease.

(It might be noted that some social factors have been found to be far more predictive of schizophrenia than genetic factors—but that is a different discussion.)

Many processes, one result. How does this come about? Part of it, I think, is a trick of language. We group individual cases of ALS or schizophrenia as the same disorder, even though the biological factors at play may be totally different. Furthermore, the actual symptoms of the disorder may be mutually exclusive between two individuals (for example, a schizophrenic suffering primarily from flat affect, versus one suffering from hallucinations). Are these really the same disorder? By what criteria are we grouping them? One answer was provided by Ludwig Wittgenstein, who recognized that our cognitive-linguistic categories are not defined by a set of essential features, but by overlapping similarities. Perhaps there is no essential core of schizophrenia! With its many determinants and many manifestations, there could be many schizophrenias, which are nonetheless grouped under the same header. Our language does not represent an exact reality but an approximate one.

Personality

Whether you prefer to use the MBTI, the Big 5, or any number of other measures, the ideas of multiple determination and family resemblance categorization is readily applicable. Investigations of what these constructs are is a favourite pastime of mine and, I assume, of most of my readers. However, these often result in headaches and inter-theory conflict. Which ones are correct? What do we do about those that seem incompatible? I will focus on introversion and extraversion as an example. Here are a few of my favourite theories:

The 20th century psychologist Hans Eysenck saw introversion/extraversion as a measure of how outgoing and interactive a person is with others. He hypothesized that this difference was grounded in a difference in brain arousal. The correspondence is a bit counter-intuitive. An extravert would be characterised by a lower baseline level of cortical arousal, and as a result would seek stimulation to bring their level up to a desired amount. An introvert would be chronically over-aroused, and as a result would seek to minimize the external stimulation they encounter.

Elain Aaron pioneered a new personality category, called the “Highly Sensitive Person”. While technically separate from introversion, there is a high degree of overlap and analogy. Somewhat like Eysenck’s theory, HSPs are characterized by a heightened sensitivity to sensory stimuli, or their own cognition or emotions (or a combination of these). This results in a timid and careful approach to the outside world, as they are more likely to be overwhelmed by a too-intense stimulus.

The biological theory forwarded by many modern psychologists has to do with the dopamine reward system of the brain. Extraverts have been found to be more sensitive to activity in this circuit. In other words, they are more reward-motivated. This has the effect of pulling them more readily and eagerly into active engagement in the outside world. Specifically, this would correspond to the sub-trait of “Enthusiasm”.

Finally, Jung thought of introversion as an attitude that favoured the inner world of the psyche, while extraversion favoured the outer world of things. However, his exploration of the types involves a lot more nuance than this general formulation suggests. Psychological Types is packed with statements and observations that often seem only tenuously related to the central theme. However, this is in keeping with the thesis of my essay. What if there is no one introversion and no one extraversion? What if the only thing binding the many versions together is our categorical mode of thought, rather than any single biological reality?

This is perhaps a bit too strong. For example, it’s an empirical fact that the many facets of the Big 5’s extraversion are highly correlated. There must be some set of biological trends that support this. However, it’s also true that the same individual may be astronomically high in one facet and at the bottom of another for the same over-arching trait. We might conclude that there are some diffuse biological patterns out there, but they are clothed and warped by our cognitive-linguistic constructions.

What’s the take-away here? One may be a more relaxed attitude towards any attempts to find the essence of a psychological category. It may not exist, although a diffuse “family resemblance” pattern might. That is not to say that we shouldn’t scientifically validate our hypotheses about what this pattern is made up of–just that multiple versions might exist in parallel, and that a greater precision is possible when describing two people as introverts, or when observing two cases of schizophrenia. The structure of personality is perhaps less like a series of well-defined islands and more like an ocean: A macroscopic pattern of currents that, when observed more closely, are a heterogenous assemblage of fish and flotsam.

Some links:

ALS fact sheet https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/Patient-Caregiver-Education/Fact-Sheets/Amyotrophic-Lateral-Sclerosis-ALS-Fact-Sheet

Genetics of schizophrenia https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5380793/

Family resemblance categories https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Family_resemblance

Introversion and extraversion https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Extraversion_and_introversion

“Highly sensitive person” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sensory_processing_sensitivity

Read my previous post on Psycho-Cybernetics first!

In my essay on Psycho-Cybernetics, I’m in some ways going far afield from the Jungian psychology that populates the rest of my blog. Psycho-Cybernetics presents a manual for optimism and worldly success, while Jung’s philosophy of the path to enlightenment leading through the Shadow parts of the personality is very, very different. Much of Jungian psychology is a meditation on the ugly parts of life. It involves including your worst tendencies in your self-image. However, I think that’s where the reconciliation lies. In terms of their structural understanding of the psyche, these two takes are comparable.

Jung once said that the first half of life should be dedicated to forming a healthy ego, and the second half to tearing it apart and going inwards. I think Psycho-Cybernetics is just such a manual for developing a “healthy ego”. And, in terms of its focus on optimism and goal-setting, it corresponds to the extraverted side of life, albeit simultaneously involving the introverted side through its use of imagination and Stoic independence.

In one line of Psycho-Cybernetics, Maltz admits that focusing on the negative once or twice per year is probably a good thing, presumably for keeping oneself humble and aware of one’s Shadow. A friend told me that there is a season for growth, and a season for tilling the soil and reducing everything to dirt. And I think that just such a cycle is the best course for young people. It doesn’t work to be the brooding melancholic all the time, even if there is a kind of wisdom associated with it. Neither is it sustainable to be a ball of sunshine forever. Without acknowledging the wrong things in life, they erode at the structure of the mind like rats or termites eating the timbers.

In terms of Max Luscher’s colour psychology, Psycho-Cybernetics surely corresponds to the Orange-Red side of life, and Jung to the Dark Blue; to the Animus and Anima of the personality respectively; to an elaboration of the Heroic Consciousness and the Deep Unconscious.

In terms of cybernetic theory, Maltz was influenced in part by Alfred Adler, Jung’s contemporary, who pioneered many aspects of the ideas of goal-directedness and success-striving. Jung was also well aware of the teleology of the psyche. He thought it was a forward-facing thing, rather than one dictated primarily by personal history as Freud thought.

These comments might seem random and incomplete, and they are. They’re the first attempts at a synthesis, the various works I’ve summarised on this blog coming together as a mosaic. I welcome any comments or suggestions for further reading!

Though it was published in 1960 as a self-help book, Maxwell Maltz’s Psycho-Cybernetics is the combination of two powerful psychological ideas. The first is that of the “self-image”, which has become well-known with the advent of cognitive behavioural therapy as well as the broader self-esteem movement. The second is the idea of the human mind as a cybernetic system. “Cybernetics” originally referred to the circuitry of guided ballistic missiles, whose navigational systems consisted of a target and positive and negative feedback mechanisms to keep in on course. In the human analogy, the goal is in response to a need or desire, and the positive and negative feedback mechanisms are our positive and negative emotions. Finally, Maltz thinks of creative imagination as the tool than can be used to influence both of the former systems to the user’s benefit and well-being. This essay will provide a summary of these main ideas and their consequences.

The idea of the self-image or self-concept might be familiar to the reader. It states that you can’t exceed the limitations you place on yourself mentally—that you believe to be true of yourself. According to theorists, the self-image prescribes the “area of the possible”. A narrow view of yourself will limit what you can do in practice, whereas an open view may allow you to excel and discover new things about yourself. What is the self-image exactly? Maltz cites the psychologist Prescott Lecky, who thought of the personality as a system of ideas that must above all else be consistent. The “ego ideal”, or self-image, is the keystone of this system. All beliefs about the world hinge on beliefs about the self. Apart from physical limitations, all limits or possibilities stem from this complex. According to Maltz, this is why plenty of “positive thinking” psychology doesn’t work. These techniques try to change a person’s thinking about their situation or environment, attacking the periphery rather than the center. As such, the changes can’t persist.

Maltz personally encountered the power of the self-image in his clinical practice as a plastic surgeon. Clients would come to him asking him to fix their disfigurements, which they believed were ruining their lives in one way or another. However, the vast inconsistency in the way that these clients responded to surgery alerted him to the psychological dynamics at play. Some clients would come to him with scars or abnormalities; some with perfectly normal and even handsome features, which they nonetheless saw as robbing them of happiness. The difference after surgery was even more striking. Some clients would seem completely transformed in terms of their personality. Some would stay exactly the same; and some would even insist that Maltz hadn’t touched a single thing with his scalpel. In addition, shame or pride about a physical feature was not universal but depended on the context. A scar across the cheek destroyed an American salesman’s confidence, but was a status symbol in the underground sabre-dueling rings in Germany at the time. This indicated to Maltz that the essential factor wasn’t the reality of a person’s appearance, but their beliefs about their appearance, and what those beliefs meant for their self-image.

This ties into a larger discussion on the power of belief in psychology. Our modern scientific-materialist ethos might influence us to believe that we naturally think in terms of what is factual and real, but it’s more correct to say that we think and act based on what we believe to be true. Belief is not a late-stage function in behaviour: Though beliefs may be derived from higher cognitive processes like reasoning, they go to form the basis of our perceptual and emotional experience. For example, you might think that the fight-or-flight reflex acts pre-consciously to real things in the environment, regardless of ideas or beliefs. But if a man encounters a bear in the woods so that his blood starts pumping and his muscles jolt into action—but the bear is actually an actor in a bear-suit—then clearly the nervous system is reacting to the idea of a bear rather than a real life-threatening situation.

The decisive influence of belief over behaviour, including subconscious or automatic behaviour, is also apparent in the twin suggestion-based phenomena of hypnosis and placebo. Under hypnosis, a weightlifter can be made to exceed their normal lifting capacity or struggle to lift a pencil. A person told that they are standing in the arctic may shiver genuinely. There are plenty of weird results to be had by suggesting an idea under the state of hypnosis. However, Maltz argues that there is no fundamental difference between behaviour under hypnosis and normal behaviour. They both simply consist of acting on what is believed to be true about oneself or the environment. In fact, in the process of changing beliefs about yourself—changing the self-image—it might be more correct to say that it’s a matter of de-hypnotizing yourself from false beliefs, provided that the new image is closer to reality. In placebo, which is the most-studied medical phenomenon and the biggest thorn in the side of pharmaceuticals, a sugar pill can have dramatic effects on a person’s somatic or mental health provided they believe they’re taking a functional, novel medicine. Most market drugs barely manage to exceed the effect produced by placebo, if at all.

The second main idea presented in Psycho-Cybernetics is that of the mind as a cybernetic system. It’s theorized that other animals also operate under the same principle. They have a goal in mind— “get food, get water, copulate”—and positive and negative emotions—gratification and lack—to motivate them and let them know how close they are to the goal. We can surmise that they have this much since the limbic system or “emotional brain” is largely conserved between humans and other mammals. However, Maltz argues that while this animal system is dictated by instinctual goals and basic needs, we have a greater capacity to consciously set new, complex goals. Indeed, the prefrontal cortex, which is enormous in humans compared to other mammals, is the seat of planning and executive decision-making (meaning its activity can influence and override other parts of the nervous system). Cybernetics comes from the Greek word meaning “steersman”, and in this theory the conscious mind is the steersman of the whole organism.

What significance does this have for the self-help domain? If the nervous system is a cybernetic system, then at least a significant portion of our positive and negative emotion is felt in relation to a goal. Happy feelings indicate we’re moving closer to our imagined destination, and sadness, anxiety, and anger tell us that we are off-course. But how many of us know what are goals are? They tend to be muddled, uncertain, or seemingly non-existent. Even worse, Maltz suggests that most people are oriented towards negative goals—towards failure. According to his take on cybernetic theory, our job as an “ego consciousness” is to submit goals to our automatic systems that then carry it out. This can be illustrated in a task as simple as picking up an object. The amount of muscle fibres and the pattern of contraction is huge and complex, but it is all taken care of subconsciously. We only need to target the object with our will—plan the broad strokes of the movement in our imagination—and the automatic systems take care of the rest. When we worry incessantly and picture our future failings and shortcomings, we are inadvertently orienting our nervous system towards this destination. What we expect to happen, what we believe will happen, will most likely happen: The Self-Fulfilling Prophecy.

Maltz offers advice on how to handle this system. For one thing, while anxiety has its uses, and was surely essential to our ancestors who had to be cautious in dangerous environments, our over-use of it manifests mostly as inhibition and failure-drive. Instead of being consumed by negative things that might happen, focus on a positive outcome. Orient yourself towards a goal that you believe will make you happy and fulfilled. Much of the fulfillment will come from incremental progress towards it, since according to the cybernetic theory, positive emotions are the positive feedback system—the “You’re on the right course” signal—but you’ll simultaneously be making progress towards a better situation. Of course, “happiness” is not the not the only—or even the recommended—goal. Any undertaking will work in the same way, whether the goal is chosen out of want, responsibility, or necessity. Picturing success and making progress towards it becomes a primary source of contentment and meaning, and picturing success rather than failure will simply make that outcome more likely.

There is also the question of how to handle the negative feedback system. In a cybernetic system, negative feedback is used to indicate error— “You’re off course”—and once the system corrects the error, it’s over. The errors are not stored in memory. Only the right course is stored so that it can be repeated later. You can observe this in infants learning to move or speak. Random, inarticulate movements are refined into the smooth, automatic movements we spoke of earlier, as the baby gropes around and moves its limbs in a trial-and-error fashion until it figures out the desired pattern. Babbling is also thought to be the expression of all possible phonetic sounds, which are narrowed down to suit what becomes the child’s mother tongue. What this is saying is that a negative experience is to be learnt from, once, and then the associated memory can be forgotten. If a bad memory persists for a long time, it might indicate that it hasn’t been used to “correct the course”. Unfortunately, some experiences can be so painful that it’s easier to push them down whenever they’re recalled. But they may dissipate if they’re taken for what they’re worth: a lesson for the future.

Another recommendation by Maltz is to use relaxation to your advantage. Armed with the knowledge that conscious-you is linked to a complex automatic mechanism, you can optimize it by simply not messing with it. Maltz cites the great American psychologist William James among others as offering the wisdom that once a goal is set and the die are cast, there is no more use in worrying. Reflecting on your actions as you’re doing them has an inhibiting and distracting effect. Anxiety clogs the gears and confuses the system. Therefore, developing a habit of relaxation, in whatever way suits you, is for the best. This might sound similar to the Taoist principle of Wu Wei, which translates to “not doing”, but more accurately means “not doing with undue effort” or “acting effortlessly”.

Maltz relates these two ideas, the self-image and the cybernetic Man, by arguing that they are both subject to modification and control by humanity’s most innovative faculty: the creative imagination. Along with our materialistic belief that our accurate perception of reality drives behaviour, we also consider our ideas and beliefs to be derived from reality. The sum of our experiences from childhood to date convince us of who we are now, and we believe that this self-image is accurate. However, from Freud onwards we’ve come to know that the line between memory and fantasy is blurred. Memories are to a large extent something that we create rather than record, and with each recollection a memory changes to suit preoccupations in the present. Though features of our self-image may have their basis in past failures or admonishments from authority figures, our self-image also has a role in how memories are recorded and reproduced. This is how a person who thinks they get nothing but misfortune doesn’t recognize good luck when it comes their way, or how someone who sees themselves as a victim is always the victim of their situation. It’s also similar to the idea of “confirmation bias”, where a person only registers or perceives what they already believe.

However, Maltz claims that we can use this blurred line between memory and fantasy, between belief and reality, to our advantage. Though nasty habits of belief or an unfortunately poor self-image can be deeply-instantiated and hard to get rid of, it’s possible through the use of imagination. Maltz argues that recollection and imagination are such similar mechanisms that our nervous system can’t tell the difference between something that is experienced and something vividly imagined. In the same way that our beliefs are abstractions from experience, we can change beliefs or create new ones by spending some time imagining ourselves, our environment, or our futures in a new light. Imagining a new self-image will instantiate it in your automatic system over time. This process doesn’t have to be equivalent with “positive delusion”. Maltz notes that most people under-sell themselves by default, and have poorer self-concepts than is realistic. Besides, trying to align value judgements with “reality” is an inherently confused affair. It usually consists of people trying to measure up to an idealized cultural standard. Maltz cites a handful of studies to illustrate the arbitrariness of the inferiority complex, including one where good students performed much worse, and experienced far more stress, when told (wrongly) that the average completion time of an exam they were given was much lower than was actually possible. Therefore, this process of achieving a reasonable self-image through prolonged imagination is what Maltz refers to as “de-hypnotizing yourself from false beliefs”.

You can also use imagination to adjust your mood at any time. By stopping to imagine a scenario in which you feel content and relaxed, you’ll feel these emotions in the present. Then, you can just stay in that emotional state and re-enter the reverie whenever you need to refresh it or escape stress. While this may sound like a cheap trick, or another instance of positive delusion, consider that worrying—which we love to do in great amounts—is the same thing with the opposite valence. You picture a negative situation and it stresses you out for an indefinite amount of time! Emotions flare up and persist. Therefore, you can modulate them by delaying negative reactions or inducing positive emotions through imagination. This is where Stoic influence comes through in Maltz’s book. And indeed, he refers to Marcus Aurelius’ claim that “Nowhere, either with more quiet or more freedom from trouble, does a man retire than into his own soul, particularly when he has within him such thoughts that by looking into them he is immediately in perfect tranquility…”.

Imagination is also the function by which we set complex goals for ourselves, intertwining it with cybernetic theory. We have already discussed how clear, positive visualisation bears differently on our automatic mechanisms than anxious, muddled imaginings. There is not much to add on this front. A cybernetic system is properly ordered when it has a target, and a positive target is going to bring more rewards than a negative one.

In this essay, I have summarized what I take to be the three main ideas in Maxwell Maltz’s Psycho-Cybernetics: The self-image and the broader influence of belief over behaviour, the human nervous system as a cybernetic mechanism, and the ways in which creative imagination can modulate both of these systems. I think the self-help value of these ideas is immense, and might as well be the beginning and end of the self-help field. Most self-help books I’ve observed or explored seem to have content that appears insightful at first, but is quickly forgotten. In distilling out the psychological ideas that made Psycho-Cybernetics great, I’ve hoped to help people remember the insights by focusing on core principles and elaborating a framework rather than a method. There are plenty of methods to be found in the original book, but I think there is just as much benefit in incorporating these ideas into everyday life in one’s own personalized way.

Works cited:

Maltz, Maxwell. Psycho-cybernetics: A New Way to Get More Living Out of Life. N. Hollywood, Calif: Wilshire Book, 1976. Print.

An essay composed of stray thoughts strung together, featuring a lazy and dishonest attempt at citation.

There is one main difference between Jung’s concept of introversion/extraversion and that of the Big 5 model, which is considered the “Gold Standard” of modern personality psychology. In brief, Jung’s version is bipolar while the Big 5 uses a unipolar spectrum. This means that Jung juxtaposes introversion and extraversion as two different and opposed principles. Each one occupies a certain domain, namely that of the psychological “interior” and that of relation with the outside world. Neither one is exactly reducible to the other. Both have positive manifestations, meant not as a valuation, but technically: While from the outside, the extravert appears to be more engaging and the introvert more withdrawn, internally the introvert is also actively seeking something, but something different from external objects and object-relations. The introvert “seeks the subject”, or the meaning contained within—and native to—their own psyche [1].

Meanwhile, Big 5 introversion is essentially a lack of extraversion. Extraversion is characterized by several facets: gregariousness, assertiveness, activity-seeking, enthusiasm, and more. Depending on the study and framework used, introversion—technically “low extraversion”—is mildly correlated with neuroticism, a separate scale measuring a propensity for negative emotions and moods like anxiety and depression. But overall, introversion is presented as a second-class trait, a lack rather than an active component of the personality. Other traits that are intuitively associated with introversion, like imaginativeness, are the domain of trait Openness in the Big 5. A handful of benefits are observed in introversion, such as a tendency to do better in academia, possibly because of a greater ability to focus on one or two topics for long stretches of time, and because introverts participate in fewer distractions [2]. But nowhere is introversion explicitly associated with interiority. That said, the statistics—based on a linguistic study of personality such as the Big 5—would have trouble showing this. It’s been argued that the Big 5’s lexical basis makes it prone to pro-social biases, since language itself is a pro-social tool [4]. Therefore, extraversion would make a bigger “splash” in the factor analysis than an asocial trait like introversion. Furthermore, to an observer, inwardness is often synonymous with opacity. Introverts are best defined by what they don’treveal about themselves. A scientific investigation of introversion as a first-order trait would have to progress in more creative directions.

What does the non-psychometric research on introversion/extraversion say? Studies have found that the mesocortical dopamine reward circuit, dubbed the “seeking” or “approach” system, is more active in extraverts than in introverts [3]. The reward system is what gives us an inner incentive to pursue certain activities and acquire things we want. It plays a part in attention by ‘imbuing’ things with salience, making us expectant of a reward, drawing our energy and gaze towards them. It is also the basis of addiction, as all addictive drugs potentiate the circuit in various ways. According to Panksepp, the seeking system does not correspond to pleasure exactly, but to the emotion of enthusiasm [5]. Enthusiasm, as you might recall, is one of the major sub-facets of Big 5 trait extraversion.

All this to say that according to this research, the extravert is more expectant of reward, more incentivized to pursue and explore things in the environment, more enthusiastic, and furthermore that this might be the mechanical basis of trait extraversion. Introverts would have less activity of this system. My question is this: Is the difference so linear? It’s known that all people exhibit a wide array of behaviours and emotions, but that the stable psychometric traits best describe the ‘average point’ of those behaviours [citation needed]. Jung also thought the two types of behaviour are highly context-dependant, so that an introvert in an easy and familiar environment would be indistinguishable from an extrovert, and an extrovert left to ponder their often-ignored complexes would be anxious and inhibited. Furthermore, he thought that it is not that the magnitude of a bout of enthusiasm that is different, but that introverts and extraverts get enthusiastic about different things.

First, I will round out a relation between the seeking system and Jungian psychology. In psychoanalysis, the fact that meaning is never inherent in the object but synthesized by the subject manifests itself as “projection”. It is the individual nervous system that imbues things with salience, as if the same person were both chasing and holding up the carrot-on-a-fishing-pole. Jung calls the function that creates these projections the Anima, because in his analyses of dreams and fantasies as well as mythology and folklore, he often found it personified as a woman (or as a man in the case of a woman—the Animus). For example, the Hindu goddess Maya, who spins the web of illusions that draw people out into the play of life. And this is exactly what the seeking system does: it produces the feeling of expectancy that spurs us into activity, into exploration, work, love, and sex.

According to Jung—and this is where I think his ideas get the most complex, and as a result unlikely, but they are fascinating to share—the Anima is ‘more unconscious’ in the psyche of the extravert. Since they are more interested in things in the environment than the inner workings of their mind, the Anima—which is one of these ‘inner workings’—sits outside of the field of awareness. To perform its function, it accesses the consciousness of the extravert in a roundabout way. It projects all kinds of personal contents onto external objects, so that these objects accrue the meaning contained in the extrovert’s own soul. This contributes to the heightened salience of the outside world for the extravert. Meanwhile, since the introvert spends more of their waking life absorbed in their own psyche, they gain more direct access—not in explicit awareness, but in intimations—of the functioning of the Anima. Their attention is directed not at external projections, but at the Anima image itself and the meaning it carries internally. Salience is contained in ideas and feelings, and is extended to the outside world only insofar as things—be they books, artwork, activities, or people—correspond to and evoke this inner reality.

If we put aside the more nebulous ideas about the location, function, and image of the Anima archetype, we can generate a simple hypothesis: Introverts and extraverts get enthusiastic about different things, based on a different principle. The relative difference in the quantity of seeking system activity might be accounted for by introverts encountering salient stimuli with a lower frequency rather than a lower amplitude—or, that the experimental stimuli are geared more towards the extroverted psychology. Jung expressed the context-dependency of this dynamic in a sort of allegory: An introvert and an extravert approach a castle in the countryside. The extravert expects to meet all sorts of positive things on the inside—gracious hosts, feasts, adventures—and gets excited about entering. The introvert, more anxious with respect to the environment, is worried about guard dogs and cantankerous keepers. However, they go inside. There they find it is filled with books and scrolls like an old library. The introvert’s eye is caught by this and that and scurries about in excitement. The extravert, meanwhile, is severely disappointed. This is not nearly as stimulating as they expected. They even start to become sour and cranky, more like the demeanour of a defensive introvert than their normal sanguine state. The extravert is drawn to the possibility of excitement and adventure; the introvert, to elaborations on ideas that are personal to them.