#nihongo

Suki na hito wo wasure youto suru nante koto wa, shiranai hito wo oboe youto suru no tonaji da.

Post link

In Japan, the 2nd Monday of the New Year is marked as ‘Coming of Age Day’ or Seijin no Hi - 成人の日.

It is held for those who have matured to the age of 20 in the past year and commemorate their transgretion into adult hood.

This Coming of Age Day became an icey wonderland with the streets filling with snow.

For futher information about 2013’s Comeing of Age Day check tokyofashion’s article.

Post link

Colours (Colors) - 色(いろ)

____________________________________

Black: Kuro-i/ くろい/ 黒い

Blue: Ao-i/ あおい/ 青い

Brown: Chairo/ ちゃいろ/ 茶色

Green: Midori/ みどり/ 緑

Orange: Daidaiiro/ だいだいいろ/ 橙色

Pink: Momoiro/ ももいろ/ 桃色

Purple: Murasaki/ むらさき/ 紫

Red: Aka-i/ あかい/ 赤い

White: Shiro-i/ しろい/ 白い

Yellow: Kiiro-i/ きいろい/ 黄色い

Note:

When using colours as adjectives you will notice some end in ‘i’ and others don’t. In Japanese there are two ways which colours become adjectives 'i’ and 'no’.

1)’い’Adjectives are used as follows:

赤い車/Akai kuruma/Red car

青い車/Aoi kuruma/ Blue car

白い車/Shiroi kuruma / White car

黒い車/Kuroi kuruma/ Black car

(To form a noun, simply remove the 'i’. E.g. Akai, becomes Aka)

2)’の’Adjectives are used as follows:

紫の傘/Murasaki no kasa / Purple umbrella.

緑の傘/Midori no kasa / Green umbrella.

Or add 'いろ’ onto the end of both 'midori’ and 'murasaki’ to form ____いろ の かさ.

橙色の傘/Daidaiiro no kasa / Orange umbrella.

桃色の傘/Momoiro no kasa / Pink umbrella.

3)The following can appear as either a 'い’ or 'の’ adjective.

黄色(い/の)ペン/Kiiro-i/no pen / Yellow pen.

茶色(い/の)ペン/Chairo-i/no pen / Brown pen.

Post link

Likes & Hobbies

_______________________________________

Movie: Eiga / えいが / 映画 Music:

Ongaku: / おんがく / 音楽

Party: Paatei / ぱあてい / パーテイ

Photography: Shashinsatsuei / しゃしんさつえい / 写真撮影

Read: Yomi / よみ / 読み - or Yomu / 読む ([verb] to read)

Shopping: Kaimono / かいもの / 買い物 (買物) - or Kaimono suru / 買い物 する ([suru-verb] to shop)

Sleep: Nemuru / ねむる / 眠る [noun / ru verb]

Sport: Supootsu / すぽおつ / スポーツ

Post link

Vegetables (やさい・野菜)

Bell Pepper: Piiman / ぴいまん / ピーマン

Broccoli: Burokkorii / ぶろっこりい / ブロッコリー

Carrot: Ninjin / にんじん / 人参

Corn: Toumorokoshi / とうもろこし / 玉蜀黍

Eggplant: Nasubi (Nasu) / なすび / 茄子

Mushroom: Masshuruumu / まっしゅるうむ / マッシュルーム

Pea: Endou / えんどう / 豌豆

Pumpkin: Kabocha / かぼしゃ / 南瓜

Post link

Fruit (果物・くだもの or フルーツ)

Apple: Ringo / りんご/ 林檎

Banana: Banana / ばなな/ バナナ

Grape: Budou / ぶどう/ 葡萄

Peach: Momo / もも/ 桃

*Persimmon: Kaki / かき/ 柿

Pomegranate: Zakuro / ざくろ/ 石榴

Strawberry: Ichigo / いちご/ 苺

Watermelon: Suika / すいか/ 西瓜

*Please pardon the spelling error on the flash card.

Post link

豚[ぶた] pig

君を幸せにするために生まれてきたんだ。/ kimiwo shiawase ni suru tameni umarete kitanda. / I was born to make you happy.

私、どんな感情も持たないことにしてるの。/ watashi, donna kanjou mo mota nai kotoni shiteruno. / "I’m avoiding any kind of feeling.“

嫌な女のいない学校::::::::::::::::ありえない / iyana onna no inai gakko:::::::::::::::::arienai / "SCHOOL WITHOUT A BITCH:::::::::::::::IMPOSSIBLE."

風+髪=災害 / kaze+kami=saigai / "Wind + Hair = Disaster."

美貌はただ気を引くだけです。人格は心を掴みます。/ bibou wa tada kiwo hiku dake desu.jinkaku wa kokoro wo tsukami masu. / "Beauty only gets attention. Personality is what captures the heart."

他人の幸せを見るのが耐えられない人がいる。/ tanin no shiawase wo miru noga taerare nai hito ga iru. / "Some people can not stand to see the happiness of others."

今寝れるのを明日にとって置くな。/ ima nereru nowo asu ni totte okuna. / Do not leave what you can sleep now for tomorrow.

人間のことを知れば知るほど、ベッドが好きになる。/ ningen no koto wo shireba shiru hodo, beddo ga sukini naru. / The more I know humans, the more I love my bed.

雨降ったし空きれいやわ! / ame futta shi sora kirei yawa / The sky is beautiful after rain !

Hurry up!

Isoide kudasai!

Kanji translation:

isogu: hurry

_____________________________________________________________________

Please write down.

Kaite kudasai.

Kanji translation:

kaku: write

_____________________________________________________________________

Please interpret.

tsuuyaku shite kudasai.

Kanji translation:

tsuuyaku: interpret

_____________________________________________________________________

Please contact me.

Renraku shite kudasai.

Kanji translation:

renraku: to write to or telephone someone

_____________________________________________________________________

Please tell me how to use it.

Tsukai-kata wo oshiete kudasai.

Kanji translation:

tsukai-kata: usage

_____________________________________________________________________

Would you do me a favor?

May I ask you a favor?

Can I ask you a favor?

O-negai ga aru no desuga.

Kanji translation:

negai: wish

_____________________________________________________________________

Ashtray, please.

Haizara wo kudasai.

Kanji translation:

haizara: ashtray

失望するのは避けなさい:一日中眠るのです。- shitubou suru nowa sake nasai: ichinichi juu nemuru nodesu. - Avoid disappointment: Sleep all day.

最高の人は、最悪の時に現れる。- saikouno hito wa, saiakuno tokini arawareru. - The best people appear at the worst times.

放さないで、二度と戻れなくなるから。- hanasa naide, nidoto modore nakunaru kara. - Do not let me go, I can never return.

星を見に連れて行ってくれるのはあなただけ。- hoshi wo mini tsureteitte kurerunowa anata dake. - Only you take me to see stars.

人を喜ばせるだけの、偽りの自分にうんざりだ。 - hito wo yorokobaseru dakeno itsuwarino jibunni unzarida. - I’m tired of being who I am not, just to please people.

信頼は一度失くしてしまうと取り戻すのが大変である。- shinrai wa ichido nakushite shimau to torimodosu noga taihen dearu. - It’s so hard to regain trust once it is lost.

時に沈黙の方が言葉より傷つく。- tokini chinmoku nohou ga kotoba yori kizutsuku. - Sometimes the silences hurt more than words.

おはようございます!- Ohayōgozaimasu! - Good Morning!

Diversions such as: ( おはよー!/ おはよーうございまーす!)

こんにちは!- Kon'nichiwa! - Good afternoon!

こんばんは!- Konbanwa! - Good evening!

おやすみなさい!- Oyasuminasai! - Good night!

Diversions such as: ( おやすみ!/ おやす!)

あなたの名前は何ですか?- anata no namae ha nan desu ka? (ha = wa) - What’s your name?

私の名前は。。。です!- watashi no namae ha … desu! - My name is …!

Diversions such as: ( 私は。。。です!- I am…! / 名前です!)

何歳ですか?- Nansaidesuka? - How old are you?

…歳です。- …saidesu. - … years old.

あなたは住んでいますか?- anata ha sunde imasuka? - Where do you live?

。。。に住んでいます。 - …ni sunde imasu! - I live in …!

Maybe like : ドイツに住んでいます。- doitsu ni sunde imasu. - I live in Germany.

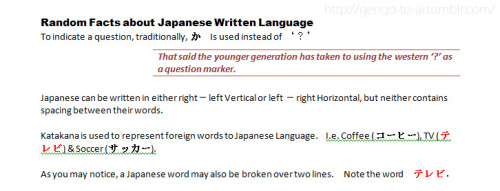

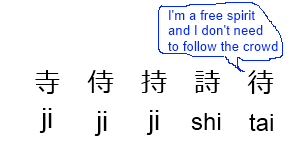

I made a couple posts about kanji and realized I should probably do an overall intro before I start throwing around words like “radical” so here goes.

Kanji (“Chinese characters”) is one of three types of Japanese letters, the other two being hiragana and katakana. Japan adapted the kanji from China and then made hiragana and katakana based on cursive/abbreviated versions of kanji.

Hiragana and katakana are both based on sound alone (hiragana is used for normal words and katakana for foreign words and extra emphasis). Kanji, on the other hand, have both a sound and a meaning.

So how are kanji put together? Well, say you’d never seen writing before, but you were trying to figure out a way to express English in pictures because that would be so much handier than having to be there in person to tell people stuff. You might come up with a system like ours where each symbol is supposed to be a sound, or you might do what the ancient Chinese did and go by meaning.

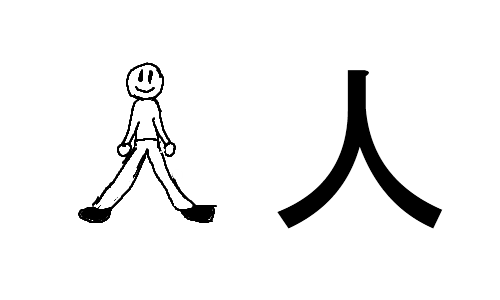

If you did that, it would start out pretty easy. You want to write “person”? Sure, we can do that.

“Sun”? No problem.

But there’s only so many simple pictures you can draw before you start needing art skills beyond what most people want to learn just to jot down a quick memo. You can start combining the pictures you have (blade+heart=ninja or whatever), but at some point this game of Pictionary is just not going to be fun for anyone anymore.

So what do we do now? The ancient Chinese decided to use one picture to tell you the meaning of the word and another to tell you about the sound.

Back to our English example, say I wanted to write the word “son”. Instead of trying to get that across in tiny family portraits or whatever, I could just write it like this, squashing two of my simple pictures together into one symbol:

It’s a person, but it sounds like “sun”. Son. Easy. Most kanji are made this way, because Chinese has a lot of words that sound alike.

The part of a kanji that carries its meaning (the “person” in this English example) is called a radical. The part that carries the sound (the “sun” here) is called a phonetic. If two kanji share a radical, that means the ancient Chinese thought they had some meaning in common. If they share a phonetic, that means that at some point in history, those words sounded similar in Chinese.

Now, languages change. Just because it made sense to the ancient Chinese doesn’t mean it still makes sense in Japanese today. But at least it helps to know this.

This system still works in Japanese because when Japanese adapted the kanji from Chinese, they borrowed the Chinese pronunciations and a lot of Chinese words, too. The Chinese-based pronunciation of a kanji is called its “on” reading (onyomi). The on-reading is most often used in compounds, where you use two or more kanji to make a word together. Most kanji only have one or maybe two on readings. Japanese dictionaries list the on-readings in katakana because they’re originally foreign, and I’ll do the same here.

The Japanese also started writing their own words with kanji, because why make a whole new symbol for “sun” when there’s a perfectly good one already out there? The Japanese pronunciation of a kanji is called its “kun” reading (kunyomi). Kun-readings are usually used for standalone words where the kanji isn’t combined with others. Many kanji have multiple kun readings. Dictionaries list kun-readings in hiragana, and so will I.

So to summarize:

- Kanji can be either a simple picture of something or a combination of those simple pictures.

- When you combine simple pictures, often one (the radical) conveys a meaning and the other (the phonetic) conveys the sound.

- Kanji originally came from China, so they have pronunciations based on Chinese (on-readings) in addition to the native Japanese pronunciations (kun-readings).

Good luck learning kanji!

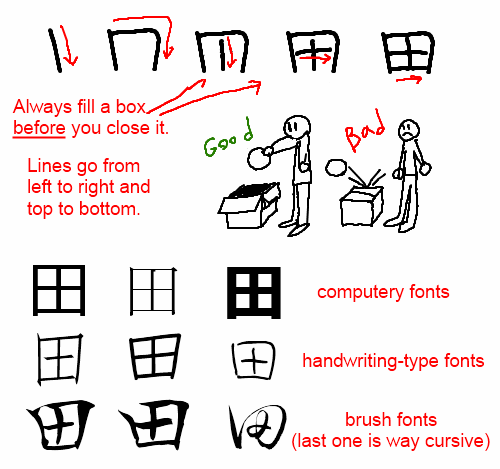

This kanji means “field”, especially “rice field”. It’s just an aerial view of four little fields separated by paths.

田 can be pronounced でん (especially in compounds with other kanji), but it’s usually た (which gets changed to だ in some places where it sounds better/is easier to say). There aren’t a ton of normal words that use it.

- 田んぼ(たんぼ) rice field

- 油田(ゆでん) oil field (油 oil)

But 田 is super popular in family names. Japanese family names often sound like descriptions of places, and farming was a common profession when these names were created, so you’ll see it a lot.

- 本田(ほんだ) Honda (本 main, original)

- 田中(たなか)Tanaka (中 middle)

This, to the best of my tablet writing ability, is how you write a 田 (I included a bunch of different examples of font styles so you aren’t totally stuck with my handwriting):

So there you have it. 田.

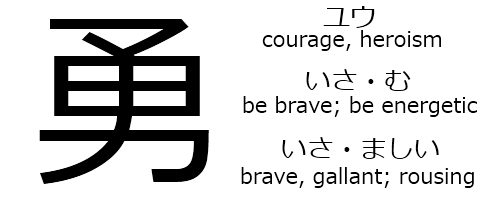

Here’s a kanji which means brave:

勇 is pronounced いさ- in native Japanese words and ゆう in compounds with other kanji. (side note: on the off-chance that you’ve ever watched Dennou Coil, there’s a character whose name is 勇子 (Yuuko) but whom everyone calls Isako because there’s another Yuuko with a different spelling (優子) running around. Both readings, free to Dennou Coil fans. Limited-time offer.)

勇 is used in a couple of common words which also basically mean brave:

- 勇気(ゆうき) courage (気 spirit)

- 勇敢な(ゆうかん) brave (敢 bold, daring)

When you see 勇 in a small font size, it can be intimidating at first. But if you know a few other kanji you might notice that it’s basically just a katakana “ma” マ on top of the kanji for man/boy/male 男. Which is good for anyone who’s heard the song Shounen Brave, about a guy (Seto) who never felt brave as a kid but one day used all his courage to reach out to a lonely girl (Mary) and befriend her. Observe:

マ is the first letter in the name Mary (マリー).

And Seto is a guy, right?

So even though Shounen Brave doesn’t have a PV, it has a kanji and isn’t that what really matters?

It turns out that if you know the kanji 人 (person)

and you watch enough Blue Exorcist

at some point the kanji 火 (fire) starts looking like a little person 人 with two little flames coming out of his head.

I HAVE REACHED THAT POINT.

So Japanese is in the habit of not actually telling you who’s doing what actions.

たべます。 “Eat.” = (I) eat/ (you) eat/ (he) eats/ (she) eats/ (they) eat/ (we) eat/ etc.

This is called an implied subject, and we do it a little bit in English too.

“Clean your room.” = (You) clean your room.

“What did you do today?” “Went to school.” = (I) went to school.

But in Japanese, it’s sort of the default. You often don’t say who did something unless it’s not clear or you want to emphasize it. Everyone just kind of figures it out from context. This is a challenge for students of Japanese before they get used to it, but it’s normally fine for native speakers. The most heartwarming part of the song Souzou Forest, however, actually kind of depends on a native speaker misunderstanding an implied subject. Let’s watch!

(warning: there’s a freaking doctoral dissertation about Souzou Forest under there. Proceed with caution)

[If you haven’t heard of this song before, it’s part of the Kagerou Project, a series of Vocaloid songs which all come together to make a surprisingly complicated story. The song started out being called Souzou Forest (想像フォレスト or “Imagination Forest”) and was renamed Kuusou Forest (空想フォレスト or “Fantasy Forest”); you will see people use both titles. It comes with a music video; go here for the original video from the creator’s Nico Nico account or here for a fan’s cover on Youtube with English subtitles.]

First, some quick rules of thumb for dealing with implied subjects:

- Use your common sense. If Bob saw a bird earlier and you’re seeing the words “flew away” now, it’s probably the bird unless Bob is getting super metaphorical about something.

- Look for the “main character” of the sentence/paragraph. If we’re talking about how Bob’s day went, Bob is probably going to be the subject of most of the sentences in our story. If a new person just appeared a few words ago, we’re probably talking about what that person did next.

- If there’s absolutely zero context, they’re probably talking about themselves (if the sentence is a normal statement) or you/the listener (if it’s a command or a question).

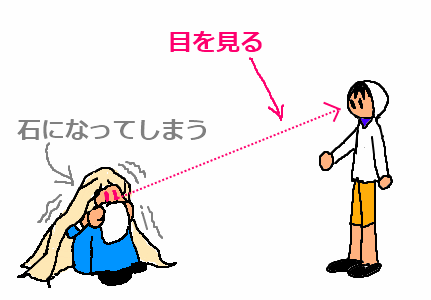

On to the song. Souzou/Kuusou Forest is about a girl (Mary) whose grandmother was basically Medusa. She lives in a house in the forest all alone, partly because she’s worried about turning people to stone with her crazy gorgon eyes and partly because every time she’s seen people they’ve been afraid of/violent towards her.

(Note that she gets through her entire life story with only three uses of the word “I/me/my” 私(わたし). For comparison, in the subtitled version in the link up there she uses I,meandmyroughly 20 times by my count. Japanese loves implying things.)

One day a boy (Seto) shows up at her door and she flips out and hides in a corner. She tries to warn him of the danger:

目を見ると石になってしまう。

- 目(め)eye/eyes; を (object marker); 見る to look; と if; 石(いし) stone; ~になる turn into~; ~てしまう do ~, and ~ is bad.

- “(sentence 1)と、(sentence 2)” means that if sentence 1 happens, sentence 2 will happen naturally/automatically, or that sentence 2 happened all on its own when I did sentence 1.

- (verb)てしまう can mean that (verb) is irreversible, or that it would be sad if (verb) happened, or both.

“If (you) look at (my) eyes, (you’ll) turn to stone!”

…or at least that’s what Mary intends to say. But all this sentence actually tells you is that when someone looks at some eyes somewhere, something turns to stone. The subjects of “looks at eyes” and “turns to stone” are implied.

Let’s see. “Looks at eyes.” There are only two pairs of eyes in the room (Mary’s and Seto’s), so no matter how you interpret it they’re looking at each other. No worries there. But what about the subject of “turns to stone?" Mary (and the audience, which knows her backstory) thinks it’s pretty obvious that Seto would be the subject of both "look at eyes” and “turn to stone.” You’ve got a Gorgon and a regular dude in a room together, what else could be going on in that sentence? Context wins the day.

Seto, on the other hand, has not been blessed with the sort of context that we all take for granted these days. He may not even know that Gorgons are a thing that exists in actual reality, let alone that he’s talking to one. All he knows is that he found a random hermit house in the woods and the girl inside freaked out when she saw him and is now cowering in a corner covering her face. Based on the fact that people are usually talking about themselves, plus the fact that Mary, frozen in fear, is the most stone-like thing in the room, Seto concludes that Mary must have some kind of crippling social anxiety.

“If (I) look at (people’s) eyes (I) turn to stone” –Seto’s interpretation

Seto knows that feel, so he decides to comfort Mary (lines photoshopped into single pictures for space concerns):

僕だって石になってしまうと怯えて暮らしてた。

- 僕(ぼく) I; だって also, even (as in “even I do that”); 石(いし)になってしまう turn to stone; と quotation marker; 怯える(おびえる) be afraid; 暮らす(くらす) live; ~てた was doing

- This と is different from the "if” と above. It marks a quote. Here, he’s quoting his own thoughts, the ones that made him afraid.

- ~てた is a contraction of ~ていた (was doing~ habitually in the past).

“I used to live my life afraid of turning to stone too.”

でも世界はさ、案外怯えなくて良いんだよ?

- でも but; 世界(せかい) world; は (topic marker); さ (emphasis, especially for an explanation); 案外(あんがい) surprisingly, unexpectedly; 怯える(おびえる) be afraid; ~なくて良い(なくていい) it’s okay/fine if you don’t~; んだ (emphasizes an explanation); よ (even more emphasis)

“But I’ve found that the world isn’t as scary as you’d think, you know?” (literally “But the world is surprisingly okay to not be afraid of EMPHASIS EMPHASIS EMPHASIS”)

D'awww. Seto’s so sweet.

And so lucky that Mary’s eyes aren’t as potent as Grandma’s. Context saves lives, man.