#japanese grammar

How to dehumanize a baby, ft. Abel and The Way Japanese Numbers Work

So you know how in English, when we say how many of something there are, we usually just say [number] [thing]…but sometimes you need another word? Something like “five sheets of paper” instead of “five papers,” or “two sticks of gum” instead of “two gums.”

Japanese numbers are like that, but with everything.

You don’t just have five sheets of paper, you also have a couple sheets of blanket, 52 sheets of playing card, a sheet of cheese on your burger. The word for “sheet(s) of something” is 枚(まい)

You have five sticks of finger on each hand, which you use to hold a stick of pencil while you write, and there are many more sticks of hair on your head. The word for “stick(s) of something” is 本(ほん)

Words like ~枚 and ~本 are called countersorclassifiers, and there are a bunch of them depending on what type of thing you’re counting. So if you’re saying that there’s one of something, it could come out as all sorts of different words:

- 一枚(いちまい) one flat thing

- 一本(いっぽん) one long cylindrical thing

- 一人(ひとり)one person

- 一個(いっこ) one small roundish object

- 一匹(いっぴき) one small animal (cats, dogs, fish, rodents, bugs…)

- 一つ(ひとつ) one thing that doesn’t fit neatly into other categories

- and many more!

I bring this up because of what Abel called poor unborn Yukio in the new Blue Exorcist chapter. When he was told that the doctors were trying to take Yuri away from the commotion surrounding her first (very demonic!) newborn twin so she could give birth to the second (less demonic!) one, he responded:

止めろ。腹の中にはまだ一匹残っている。

Stop them. She still has one more of those things left in there.

- 止めろ stop them! (imperative form of とめる “stop someone from doing something”)

- 腹(はら)belly, abdomen

- ~の中に(~のなかに) inside of ~

- は makes 腹の中に “inside (her) abdomen” the topic of the sentence

- まだ still, yet

- 一匹(いっぴき)one (small animal)

- 残っている (のこっている) is left, is remaining (from のこる “to remain/be left over”)

So he says there’s one more baby…but he didn’t use the counter for people, now did he? That would be 一人. He said 一匹, with the counter for smallish animals.

Really drives home the fact that he sees the twins as vermin to be exterminated, doesn’t it?

Post link

So Japanese is in the habit of not actually telling you who’s doing what actions.

たべます。 “Eat.” = (I) eat/ (you) eat/ (he) eats/ (she) eats/ (they) eat/ (we) eat/ etc.

This is called an implied subject, and we do it a little bit in English too.

“Clean your room.” = (You) clean your room.

“What did you do today?” “Went to school.” = (I) went to school.

But in Japanese, it’s sort of the default. You often don’t say who did something unless it’s not clear or you want to emphasize it. Everyone just kind of figures it out from context. This is a challenge for students of Japanese before they get used to it, but it’s normally fine for native speakers. The most heartwarming part of the song Souzou Forest, however, actually kind of depends on a native speaker misunderstanding an implied subject. Let’s watch!

(warning: there’s a freaking doctoral dissertation about Souzou Forest under there. Proceed with caution)

[If you haven’t heard of this song before, it’s part of the Kagerou Project, a series of Vocaloid songs which all come together to make a surprisingly complicated story. The song started out being called Souzou Forest (想像フォレスト or “Imagination Forest”) and was renamed Kuusou Forest (空想フォレスト or “Fantasy Forest”); you will see people use both titles. It comes with a music video; go here for the original video from the creator’s Nico Nico account or here for a fan’s cover on Youtube with English subtitles.]

First, some quick rules of thumb for dealing with implied subjects:

- Use your common sense. If Bob saw a bird earlier and you’re seeing the words “flew away” now, it’s probably the bird unless Bob is getting super metaphorical about something.

- Look for the “main character” of the sentence/paragraph. If we’re talking about how Bob’s day went, Bob is probably going to be the subject of most of the sentences in our story. If a new person just appeared a few words ago, we’re probably talking about what that person did next.

- If there’s absolutely zero context, they’re probably talking about themselves (if the sentence is a normal statement) or you/the listener (if it’s a command or a question).

On to the song. Souzou/Kuusou Forest is about a girl (Mary) whose grandmother was basically Medusa. She lives in a house in the forest all alone, partly because she’s worried about turning people to stone with her crazy gorgon eyes and partly because every time she’s seen people they’ve been afraid of/violent towards her.

(Note that she gets through her entire life story with only three uses of the word “I/me/my” 私(わたし). For comparison, in the subtitled version in the link up there she uses I,meandmyroughly 20 times by my count. Japanese loves implying things.)

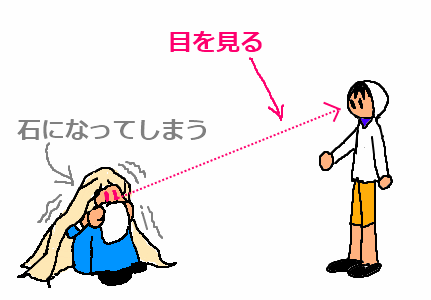

One day a boy (Seto) shows up at her door and she flips out and hides in a corner. She tries to warn him of the danger:

目を見ると石になってしまう。

- 目(め)eye/eyes; を (object marker); 見る to look; と if; 石(いし) stone; ~になる turn into~; ~てしまう do ~, and ~ is bad.

- “(sentence 1)と、(sentence 2)” means that if sentence 1 happens, sentence 2 will happen naturally/automatically, or that sentence 2 happened all on its own when I did sentence 1.

- (verb)てしまう can mean that (verb) is irreversible, or that it would be sad if (verb) happened, or both.

“If (you) look at (my) eyes, (you’ll) turn to stone!”

…or at least that’s what Mary intends to say. But all this sentence actually tells you is that when someone looks at some eyes somewhere, something turns to stone. The subjects of “looks at eyes” and “turns to stone” are implied.

Let’s see. “Looks at eyes.” There are only two pairs of eyes in the room (Mary’s and Seto’s), so no matter how you interpret it they’re looking at each other. No worries there. But what about the subject of “turns to stone?" Mary (and the audience, which knows her backstory) thinks it’s pretty obvious that Seto would be the subject of both "look at eyes” and “turn to stone.” You’ve got a Gorgon and a regular dude in a room together, what else could be going on in that sentence? Context wins the day.

Seto, on the other hand, has not been blessed with the sort of context that we all take for granted these days. He may not even know that Gorgons are a thing that exists in actual reality, let alone that he’s talking to one. All he knows is that he found a random hermit house in the woods and the girl inside freaked out when she saw him and is now cowering in a corner covering her face. Based on the fact that people are usually talking about themselves, plus the fact that Mary, frozen in fear, is the most stone-like thing in the room, Seto concludes that Mary must have some kind of crippling social anxiety.

“If (I) look at (people’s) eyes (I) turn to stone” –Seto’s interpretation

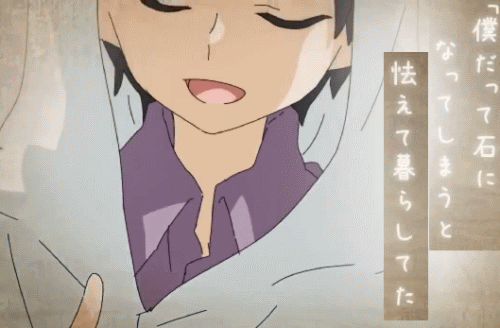

Seto knows that feel, so he decides to comfort Mary (lines photoshopped into single pictures for space concerns):

僕だって石になってしまうと怯えて暮らしてた。

- 僕(ぼく) I; だって also, even (as in “even I do that”); 石(いし)になってしまう turn to stone; と quotation marker; 怯える(おびえる) be afraid; 暮らす(くらす) live; ~てた was doing

- This と is different from the "if” と above. It marks a quote. Here, he’s quoting his own thoughts, the ones that made him afraid.

- ~てた is a contraction of ~ていた (was doing~ habitually in the past).

“I used to live my life afraid of turning to stone too.”

でも世界はさ、案外怯えなくて良いんだよ?

- でも but; 世界(せかい) world; は (topic marker); さ (emphasis, especially for an explanation); 案外(あんがい) surprisingly, unexpectedly; 怯える(おびえる) be afraid; ~なくて良い(なくていい) it’s okay/fine if you don’t~; んだ (emphasizes an explanation); よ (even more emphasis)

“But I’ve found that the world isn’t as scary as you’d think, you know?” (literally “But the world is surprisingly okay to not be afraid of EMPHASIS EMPHASIS EMPHASIS”)

D'awww. Seto’s so sweet.

And so lucky that Mary’s eyes aren’t as potent as Grandma’s. Context saves lives, man.

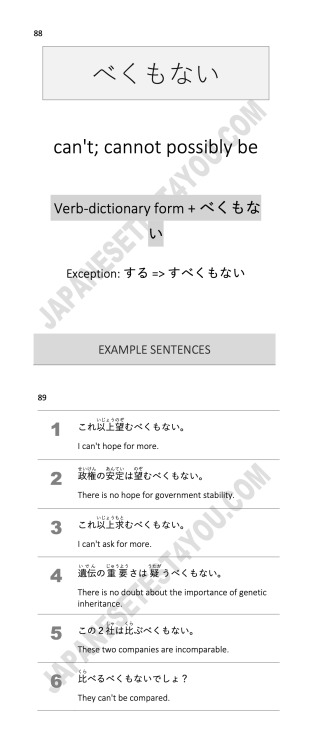

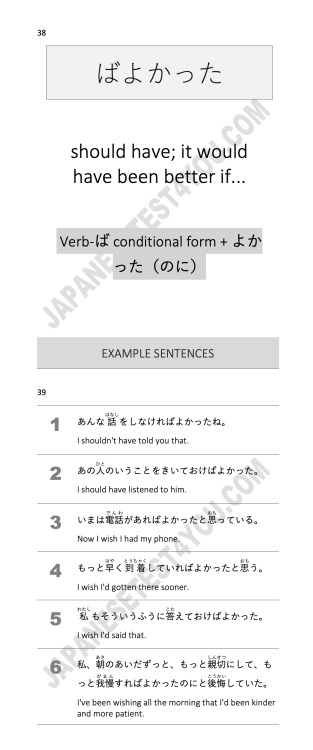

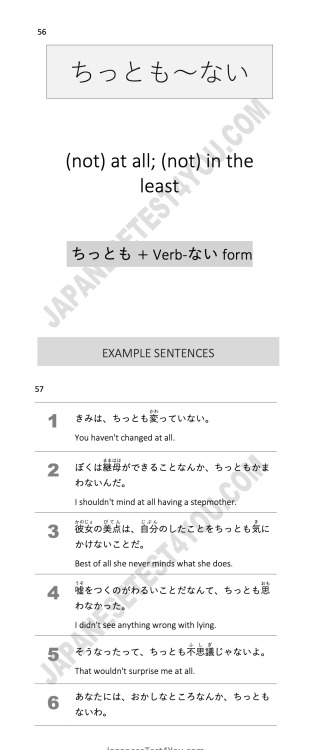

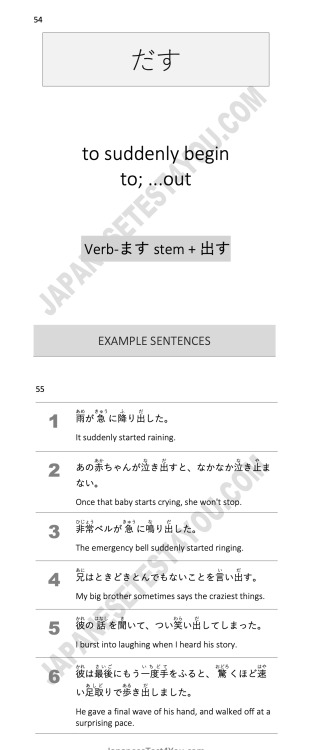

(PDF) THE SUMMARY OF 500 JAPANESE GRAMMAR POINTS (JAPANESE EDITION)

This was posted in the Learn Japanese subreddit by user KnowYourJapan. I love love love how the grammar points are categorized by their semantic meanings which makes them a lot easier for me to learn.

Hello, everybody! I hope you all have had at least a good start into the New Year.

A new year means new opportunities, and of course, new decisions. Let’s talk about how to decide things in Japanese.

There are many different moments when you have to make a decision. Do you want the soup or the salad? Pokemon Sun or Pokemon Moon? A morning class or an evening class? In English, this is a pretty unanimous phrase:

“I decided on the soup.” “I decided I want Pokemon Sun.” “I decided to take the morning class.”

More casually, it can be reduced to “I picked” or even “I’m doing”, the latter being a very interesting phrase. You can’t actually “do” a soup, but it’s another way to say that a decision has been made. In that respect, Japanese is similar. But for now, let’s just talk about 決める/きめる.

決める is the literal closest word to the English “to decide”. I mean, 決める means just that, “to decide”.

ニューヨークに行くことに決める。

I decided to go to New York.

パーティのひどりを決めました。

I decided on a date for the party.

その大学に入っていると決めます。

I decided to enroll in that college.

Now, some of you may look at the sentences/translations and feel it’s simple enough. But someone of you may have noticed a small, yet essential difference between the examples: the particles. That’s right, 決める uses に, を, and と. Because it can.

This can be something that can be difficult to explain, and sometimes people don’t bother to explain it at all, but here goes.

に決める

に決める is the most standard paring. It refers to a decision being made.

りんご(をたべるのこと)に決めました。

I decided to eat an apple.

In this case, the (をたべるのこと) is implied to some degree because most likely you would have picked an apple to eat it. In general, always refer to に決める if you’re really stuck. That said, it’s hard to describe the full usage of に決める without going into the other two.

を決める

This is a bit more nuanced than the former example. を決める doesn’t state the decision directly, but rather what the category that is decided upon. Let’s go back to the previous example of eating an apple. If I had to use を決める:

くだものを食べるのことを決めました。

I decided upon a fruit to eat.

Here, the result would likely still be the same: I picked an apple. But this example doesn’t tell you the exact fruit I picked. Instead, it described the category. If we go back to the first を決める example:

パーティのひどりを決めました。

I decided on a date for the party

I’m not telling you the exact date here, am I? If I did, it would be more like this:

パーティのひどりは2月11日に決めました。

I decided the date of the party will be February 11th.

Here, に決める is used because I am sharing the exact result of what was being decide on. Let’s go back to を決める:

くるまを決めました。

I decided on a car.

This is literally all it means. I’m not telling what kind of car, what year, or any specifics. If I did share a specific detail (like a black car or something), に決める is more appropriate because now I’m telling you I decided on a specific car/result.

と決める

と決める is interesting because while it can substitute for either に決める or を決める, it’s actually not a good regular substitute for either. Yeah, I realize I made things more confusing.

The thing about と決める isn’t that is it is following a type of translation rule, but rather an emotional one. と決める is used to create a sense of “Finally!” or “After a long time”. It’s used to convey that a lot of thought and time went into making the decision. If we look at the original example of と決める:

その大学に入っていると決めます。

I decided to enroll in that college.

The use of と決める conveys that it took a long time to decide to enroll in a specific college. This is understandable as college is usually one of those things people try to think about. Let’s look at a comparison between と決める and に決める.

まこととけっこんすることに決めました。

まこととけっこんすることと決めました。

Very literally, they both mean “I decided to marry Makoto.”. Sentence 1 conveys a more natural, easy transition to making the decision to marry Makoto. Sentence 2 conveys a more deliberate moment of consideration. In the second example, maybe there were doubts or issues regarding Makoto as a marriage partner. Maybe in sentence two it was an arranged marriage situation involving multiple options. The point is that the use of と決める means that a long train of thought was put into the decision.

Same thing with を決める:

ダイエットを決めました。

ダイエットと決めました。

Again, both mean “I decided on a diet”. を決める, like に決める, is a more neutral, natural decision making process. と決める is a deliberate, intentional choice within diets.

In summation, に決める is the Foreigner’s Privilege choice. For a non-specific decision, を決める is the best. To convey a serious and considerate decision result, と決める is better.

I’m not really going to do examples for this one because と決める can technically be used as an answer to anything (who am I to judge how long it takes for you to decide on a toothpaste?). But I will ask you to consider specifics vs categories.

Red vs Colors

Cats vs Animals

Target vs Department Stores

Halloween vs Holidays

Lavender vs Flowers

Penne vs Noodles

California vs U.S. States

By keeping in mind conveying a decision on a specific result is に決める and a decision within a category is を決める, you’ve pretty much have a grasp on the difference between the two particles.

As always, feel free to ask if any questions come up!

Hello! Today I’m going to talk about grammar forms that are “in the moment”. That is to say that two things happen around the same time.

Let’s consider these sentences in English:

When the elevator closed, I realized I forgot my wallet.

or

When you get back, please call me.

In both sentences, “when” is used to describe a moment where an action happened. If you’re beginning Japanese, your first impulse may be to translate the sentences into Japanese using “時/とき”:

エレベーターが閉まった時に、さいふを忘れてしまった気づきました。

Hmm. I don’t want to say this is completely wrong, but the correct emotional conveyance isn’t there. 時 is used when it’s a general and extended period of time (学生の時: When I was a student; 結婚した時: When I got married, for example). However, elevator doors closing is usually a swift action.

The second problem with 時 is that people usually remember forgotten things the moment it becomes too late. 時 does a poor job conveying suddenness or promptness. It’s a jack of all trades but master of pretty near nothing; learning to notuse 時 all the time is a strong sign of Japanese fluency.

So, let’s talk about things we can use to replace 時. Mostly, とたん, 次第, and 最中.

Let’s talk about とたん, since it’s the easier one to explain, but a little harder to get.

とたん

とたん’s most precise translation is “just now” or “at that moment”. It’s literally the second A happens, then B. This makes とたん the best fit for our elevator example:

エレベーターが閉まったとたん(に)、さいふを忘れてしまった気づきました。

This is much better, since now there is that understanding of “at that moment”. The listener/reader can imagine the surprise or shock of realizing you forgot your wallet when the doors closed.

I highlighted part of the sentence for a reason. You see, とたん can only be used with a past tense verb. とたん is pretty much always used in regard to an action. It’s even hard to imagine an “as soon as” sentence in English without a verb in past tense. It’s the same scenario in Japanese. Let’s translate a few:

As soon as I returned home, the phone rang.

家に帰ったとたん(に)、電話が鳴りました。

When I finished my homework, I turned on the television.

しゅくだいを終えたとたん(に)、テレビをつけました。

Just as my mom entered the room, we started laughing.

お母さんが部屋に入ったとたん、ぼくたちが笑い始まりました。

I hope you notice something about とたん in these examples:

1) とたん is always used when both clauses are past tense. You can’t say “Just as the door closed, let’s start dancing!”. Even in English that’s weird. とたん must be preceded by a past tense verb, and followed by a past tense verb.

2) I put (に) in parenthesis a lot. I did this to show that に, while used correctly in this form, can be optional. とたん only really uses に as a particle to the point where に is pretty much implied.

次第/しだい

Is it weird I like the aesthetics of this word? Yes? Okay, let’s move on then.

次第 also means “as soon as”, but it’s primarily used in the present. Let’s look at our original second example:

When you get back, please call me.

Well, とたん can’t work here because neither the first or second part is in past tense. 時 is also no good because while “returning” can take a long time, the speaker is obviously referring to a specific instance when the returning is completed. It might even be imperative that the listener/reader call ASAP.

This is where 次第 works. It actually has a second meaning of “dependent upon”, but it doesn’t always work in translation with its other meaning. At this moment, we are only regarding its “as soon as”/”immediately” meaning.

When you get back, please call me.

帰り次第、私を電話に呼び出した下さい。

Let’s note how 次第 is conjugated. The verb is put into its ます form, but the ます is cut off. Also note how the second part is a command/request. This is acceptable.

次第 also implies that the first clause can be done, so you can’t really use potential form with this. Let’s look at another example:

The moment you fall in love, you become weak.

恋をし次第、弱くなります。

Again, the same thing. A ます form verb with no ます, followed by 次第.

Now, this next note is pretty important:

DO NOT USE 次第 with に.

The issue isn’t that に can never be used with 次第. The issue that when they are used together, the meaning changes. 次第に means “to gradually –”. It’s an adverb. For example:

まどを閉め次第に, ライトをつけて下さい。

I…I wouldn’t know where to begin translating this. If the まどを閉め part wasn’t there, this could be “Please gradually turn on the lights”. But since まどを閉め is there, this sentences becomes quite messed up. If に wasn’t there:

まどを閉め次第, ライトをつけて下さい。

As soon as you close the window, please turn on the lights.

There, much better. Of course, this is a valid sentence too:

まどを閉め次第, 次第にライトをつけて下さい。

As soon as you close the windows, please gradually turn on the lights.

If this sentence seems silly to any English speakers, remember that Will Smith will smith.

最中/さいちゅう

And last but not least is 最中. 最中 means “in the middle of”. Despite the presence of 中, it doesn’t have to be the actual middle. Much like in English, 最中 has the same non-exact emotional meaning:

かれのスピーチの最中に彼女が泣きました。

She cried in the middle of his speech.

Now, it’s not always clear what the exact “middle” of something like a speech is. It could be closer towards the beginning or the end. All 最中 does is note that some moment, performance, or action was interrupted by something else.

ざっしを読んでいる最中、医者に呼ばられました。

I was in the middle of reading the magazine when I was called by the doctor.

In this example, I’m using a Verb, but in ーている form. This is acceptable. After all, you have to have been doing an action to be interrupted by it. Even in English, the verb is in -ing form even though this happened in the past tense. Let’s look at one more example.

A: 「今、何をしているの?」 “What are you doing now?”

B: 「宿題の最中だ。」 “In the middle of homework.”

At first glance, B seems to be using a fragmented sentence, but it’s actually complete: “(I’m) in the middle of (doing) homework”. This is also acceptable. It’s clear that 時 couldn’t work in this example. If someone asks what you are doing, “Homework time” is kind of a weird response. This also shows that 最中 primarily serves as a sort of “adverb” noun. It’s a noun that only serves a purpose when describing actions and moments. Therefore, it is perfectly okay to say “I am ‘Noun’”.

Let’s practice a bit, shall we? I’ll write some sentences in English, and you can think about if 時, とたん, 次第, and/or 最中 would work:

1. When you’re done with that, you can go home.

2. When the cat hissed, I started running.

3. I was daydreaming when I saw him.

4. When you are free, call me.

5. My phone always rings a lot when I am sleeping.

6. I hate it when you call me after work! I’m always in a meeting!

Alrighty, let’s see how you did:

1. それを終えたとたん、帰ってもいいです。

それをおえた時、帰ってもいいです。

In this case, both とたん and 時 are fine. The reason is that the sentence in itself doesn’t convey urgency or a sense of immediateness. However, it could. So either is fine.

2. 猫がほえたとたん、はしりました。

Here, there is a strong association with the timing of A and B. A happened first, then B. Further, both are in past tense. とたん is the winner.

3. くうそうふけっている最中にかれを見ました。

Here, the sentence is both in past tense, but the sentence doesn’t convey the sense of an immediate event. Further, “daydreaming” is more likely something to be interrupted. 最中 is the best.

However, one could make the case for 時 if this happens EVERY TIME.

4. あなたが暇になり次第、呼び出してください

あなたが暇な時に、呼び出してください。

Interestingly enough, both 次第 and 時 are acceptable in this translation, only because we don’t have further context. 次第 works well with a sense of urgency or command, while 時 works more as an invitation or a polite request. But, please note what precedes both clauses. 次第 MUST be followed by a verb. To that end, 休む could also work. If the case was for 時, then of course adjectives are fine. But for any verb, it should be in dictionary form in this case.

5. 寝ている最中に電話がいつもたくさんの音を鳴きます。

寝る時に電車がいつもたくさんの音を鳴きます。

Hnnnnn. This is also a weird context one. Remember, 最中 is best when it conveys that something has been interrupted. Naturally, sleep can be interrupted–but it doesn’t have to be. If the speaker is a hard sleeper, but then wakes up in the morning to find a lot of missed texts and calls and notifications, then 時 is better. If the speaker is trying to convey often being woken up, 最中 can be a better bet.

6. あなたが仕事の後にすぐに私を呼び出す物が嫌いだ。いつも会議の最中だよ!

Ah, a tricky two-parter! Yep, couldn’t resist. I’m sure many of you saw “I hate it when” and went through all what we talked about. You’re right to think that とたん, 次第, and 最中 aren’t correct in that part (最中 works in the second part though), but where is 時? The problem with using 時 is that a specific instance, when the listener calls, is describedas disliked by the speaker. If something has frequently happened to the point where it is a norm, and it is being described by an adjective, then 物/もの is actually the correct noun. I may do a more in depth lesson later about 物/もの, but just know that 時 is used when a moment is used as the description, 物 is used when a specific and common moment is described.

So that’s it! It was a bit of a long lesson, but the grammar is geared towards those who are a little more on the advanced side. Hopefully, I helped clear some things up!

Hello, everybody! Today, I’m going to talk about points in times a bit.

いますand あります are pretty standard verbs and some of the first words for newbies. In a nutshell, they both mean “to exist”, where います is for animate objects and あります is for inanimate objects, or rather non-living things even including events and plans. They also have secondary meanings: います also means “[Verb]-continuously” and あります also means “to happen”. We’re going to talk about the latter meanings today, and how it relates to another verb, おきます.

おきます/おく is a verb commonly meaning “to put/place”, but it has a bunch of other meanings too. We’re going to talk about the particular meaning of “doing something in advance”.

Usually, 〜ています is taught early and alone, because it has a pretty common equivalent in English. It means to do a Verb continuously, or in simpler terms “~ing”.

すしを食べています。

[I’m] eatingsushi.

ビデオゲームをしています。

[I’m] playing a video game.

When you want to put a verb into ~ing form, you need to put the verb into its て-form and put an います at the end.

Even in English, there is a noticeable difference between “I eat sushi” and “I am eating sushi”. The former is a very general statement presented as a fact, while the latter describes the current action at a specific time. Imagine this phone conversation:

A: 「B−くん、すしが食べられますか。」

B:「はい、すしを食べます。今、すしをたべています。」

A: “B, can you eat sushi?”

B: “Yes, I eat sushi. I’m eating sushi now.”

Even unconsciously, you can see how B’s first and second statement portray different things.

Now, 〜てあります isn’t the 〜ています when it comes to inanimate things. It has a meaning that can also be applied to living beings. 〜てあります is a little difficult to explain and it’s often explained with ~ておきます. The best way I can think of explaining the two of them is that ~ておきます is to do something in advance, while 〜てあります is to create a continuous situation. Unfortunately, they’re kind of similar in usage:

パーティーのために、ケーキを買っています。

パーティーのために、ケーキを買っておきます。

パーティーのために、ケーキを買ってあります。

I threw in the first sentence just for comparison review.

I’m buying a cake for the party.

I [have presently] bought a cake in advance for the party.

I [have presently] bought a cake for the party.

I realize I have made this more confusing by putting the last two sentences in past tense when the Japanese tense is clearly present, which is why I threw in “have presently”, because while it is heavily implied in Japanese, it’s a little wordy in English, and it makes more sense this way.

The point of Sentence #2 is to describe a particular action, also emphasizing that the cake was bought prior to. This is a single moment in time. The point of Sentence #3 is to describe the situation of now having the cake, and the cake is still around. This is an ongoing moment in time. Next example:

そのレストランに行きたいから、よやくしております。

そのレストランに行きたいから、よやくしてあります。

I want to go to that restaurant, so I already made a reservation.

VS

I want to go to that restaurant, so I have a reservation.

Again, sentence 1 is describing having previously done that action of making a reservation, and sentence 2 is describing the situation of having a reservation.

So in recap:

〜ています: Used to describe an action currently being done [いま]

〜てあります: Used to describe how an action creates an ongoing situation [いまから]

~ておきます: Used to describe how an action is done in advance [あとのために]

Bonus Round time: That being said, I want to briefly go over the difference between 〜てあります and just あります.

アイスクリームがあります。

アイスクリームを買ってあります。

There is ice cream.

I have bought ice cream (which is still around).

Again, slightly different pictures. The first sentences doesn’t describe any particular action, just that ice cream is, well, here. The second sentences makes it clear that the ice cream was bought (I suppose rather than home-made or stolen), or even “There is ice cream that I bought”:

私に買われたアイスクリームがあります。

This is wordy even in Japanese, and even requires the use of passive form and descriptive verbs. The previous sentence is much less wordy and more natural.