#guest post

A Guest Post by Erin

Dialogue is essential to a story especially when you are writing a slice of life story. Dialogue can be used to voice a character’s motivations, reveal information (backstory’s/history of your world) and move along the plot.

Dialogue is hard to write, so don’t be discouraged. Often, we as writers tend to write something and our audience perceives it differently than we intended. The same is true with dialogue, it’s not what we meant to say but what our audience heard.

Here are five mighty tips to help you push your dialogue further.

1. Unique POVs

Each character has their own personality and behavior, they should also have their own way of speaking that is different from everyone else. If you establish their manner of speaking early in the story, you won’t have to use dialogue tags after every sentence. Your audience will understand who’s talking.

Example:

A: Hello, how are you doing on such a lovely day?

B: Fuckin’ terrible.

A: I’m extremely sorry…what happened?

B: My mama gotta pig flu.

2. Awkward Dialogue

Dialogue is hard to write because it sounds good in your mind but on the paper, it reads awkwardly.

To avoid awkward dialogue:

- Read it aloud. If it sounds weird to you, it will sound weird to your readers.

- Utilize software. Google docs has a voice reader feature. It will read your text back to you. Through this process you can fix errors, replace misused words and fix unnatural spacing.

3. Spacing

To improve the quality of your dialogue, natural spacing, breaks, and pauses are necessary. Writing long paragraphs of dialogue without breaks will confuse your reader. It won’t sound realistic and your reader will lose their place while reading.

Also give the character something to do as they are speaking. Rarely do people simply talk without doing another activity.

4. Suspension

When writing emotional scenes, build up to the emotion. There must be a reason that this character is mad/sad/happy. Convey that in the story whether through their action or dialogue. Don’t randomly add exclamation points and all capitals. Your audience will be lost. Build the suspense whether through one scene or a few chapters.

Example:

A: Hey Lucas.

B: Yeah.

A: Remember when you told me I could borrow your pencil?

B: Yeah…??

A: I… broke it earlier…Sorry.

B: WHAT!!!?

5. Movement

Dialogue carries the plot just as actions do. Don’t be afraid to give your characters dialogue, but only when appropriate. Before writing always ask: Why should the reader care about what my character is saying? That will be a guiding factor to determine how long or short the dialogue will be.

Example:

A: I can’t believe that the King is treating us like this, its’ crazy! There will soon be war!

B: It’s been 50 years too long.

A: He must go!

B: I agree, he will be getting his just desserts soon.

*This scene explains the current situation without being unnecessarily lengthy. It also leaves the readers guessing what will happen next.

-Erin

A Guest Post by Cait

In every story, we have the main (A) plot; the detective is trying to find the jewel thief

AND

The side(B) plot; the detective is going through a divorce

Most stories contain more than one side plot. There can be as many as you like. What is the purpose of them, you say? I’ll tell you!

Side plots make the story more dynamic. They give ‘screen time’ to your minor characters, offer relief from the main tension and allow your protagonist to shine in different areas. You know what your detective is like at work, what are they like at home?

Side plots will begin after the main plot is introduced and are resolved before the main plot ends. They introduce storylines that are important, but secondary to the main plot.

How do you write side plots?

Think about:

Who are your minor characters? What role do they play in your story? Who are they in relation to your protagonist/antagonist? Do they have their own arc?

Do they have a love interest? – Common side plots involve your protagonist’s relationships. Unless you’re writing a romance story, a romance arc often belongs to a side plot. The romance doesn’t always have to work out, but it is important that your love interest is a fully dimensional, fleshed-out character. Give your readers a reason to root for, or alternatively, boo for them.

What does your protagonist’s life look like? Who are they in different environments? What’s important to them? What are their hobbies? What is their daily, mundane routine?

Where has your protagonist/antagonist been? What is in their past? How has it impacted their present self? Are they harbouring secrets? Are they holding on to something? Where do their strengths and weaknesses come from?

Where else is the conflict? You have your main conflict; catching the villain. What else is going on in their life? Are they struggling to pay rent? Do they miss their ex? Is their mother unwell?

How can all this add to the story? Do these scenes reveal important information? Do they develop your character? Do they develop relationships? Do they relate to the overall plot? Do they build the tone and message of your story?

Without any side plots, your story can become one-dimensional. Your readers may get bored, or be overwhelmed by the main arc. Give your baby dimension!

Your side plots can be whatever you like. They should add to the story as a whole, even if it is something as simple as a silly prank war between your protagonist and their neighbour. Simple things can add meaning if written well. As long as it fits your vision, write away!

-Cait

Interested in being a guest blogger? Go here and fill out our short form :)

Hi all, Patricia ( @labrattish ) again.

I’ve been meaning to post this for a small time now, but I’m in the final semester of school and it’s been hard to balance everything (anything). Cris’s brother got the package full of notes and drawings and whatnots on Monday. I just wanted to say thank you for all of it. I know it’s still really surreal for everyone. I can’t say that each day gets easier (it’s really an up and down thing), but this really made his and my day (Cris’s and his parents are currently in Puerto Rico with family). So, Thank you. Really, truly, and deeply from the bottom of our hearts. Thank you.

Post link

Yondu Week Day Three: Despair / Family / Reunion

[A/N] So I SWORE I uploaded this one, but I can’t find it anywhere on my Tumblr, so I either a) didn’t post it b) Tumblr was stupid and didn’t save the draft or c) somehow it accidentally got deleted.

Anywho, here’s day 3, which was inspired by headcanons by the awesome @shanoniusrex/@stakarbage , which can be found HERE

It’s a routine mission, but it’s Yondu’s first. It’s a small moon that Krugarr recently found was home to a healing herb that is worth hundreds of units a leaf. The mission is to find these plants and report back to the ship before nightfall.

Yondu wants to prove that he can handle a simple look-and-find job, so he sets off to search by himself. He unintentionally wanders farther and farther away from the others as he walks along – then he gets distracted following a stream he believes might lead him to the plant. He travels further and further into the tall ferns that carpet the forest floor, and before he knows it, he’s alone in the woods – and the sun is on its way down in the sky.

“Stakar?” he calls, turning around in a slow circle, looking for any signs of the party. “Martinex?” He cups his hands around his mouth. “Charlie?”

There’s nothing but silence. He stands stock-still for a second, then, fear rising in his throat, he tears back the way he thought he’d come. But he didn’t study the planet as carefully as he should have – he doesn’t know in which direction the sun sets, didn’t pay attention to what side of the trees those purple flowers grow on. Dammit! he scolds himself. Ya know better than this! Less than a year with these Ravagers and ya gone soft! Idjit, ya up and forgot all yer survival training!

“Stakar!” he yells as he runs. “Aleta! Marty! Anybody hear me?”

As the sun dips lower and lower into the sky, he begins to slow his pace. He stops at last, panting, and listens. There’s no movement except for the lonely rustle of wind amongst the ferns, and no sound except the winged creatures that cackle mockingly in the trees high above. There’s no voices calling for him, no sound of footsteps.

They left me, he realizes in shock. I - I thought they was different. His heart sinks in his chest, and he backs up against the nearest tree, sliding down its trunk into a sitting position. I’ve been lookin’ fer ‘em fer hours, but they ain’t been lookin’ fer me. He laughs ruefully to himself, shaking his head. Why was I foolish enough to think they’d keep me around? His lips purse into a tight line. I ain’t any good to nobody. I ain’t helpful like Martinex, or kind like Charlie, or brave like the Ogords. I ain’t talented or skilled or nothin’. The Kree was right, I’m jus’ a waste a’ space, ain’t worth shit. They probably couldn’t wait to get rid a’ me.

This last thought comes with something unexpected and unfamiliar – a tight feeling in his throat, and the sting of tears in his eyes. He scrubs them away angrily with a fist. I deserved this, I probably did somethin’ wrong.

He draws up his knees and rests his arms over them. He looks up to the sky. The sun is setting; he can see the three moons hanging in the sky. He needs to find shelter, and he can figure out a way to get off the planet in the coming days. His shoulders sag as he wearily climbs to his feet. No more comfortable cot, no more regular meals.

But that’s not what hurts most, that’s not what he’s going to miss. Martinex’s jokes, Charlie’s booming laughs, Aleta’s nearly-hidden smile of approval, Stakar’s voice, his comforting hand on his shoulder. Yondu has to get used to being alone again.

Yondu sets his jaw and begins to head towards the remaining sunlight. Git yer thoughts straight. If I can find that stream again, it might lead to a river or larger body of water. And wherever there’s water, there’s probably game, and possibly shelter. Hopefully he can find it before the sun is completely below the horizon.

He’s about to start walking again when he stops. He thought he heard something. An animal, maybe? He listens, but he doesn’t hear anything. He goes to take another step, when –

“Yondu!”

It’s faint. Too faint. Yondu shakes his head. “Damn imagination,” he tells himself, gritting his teeth, and takes a few more steps.

“Yondu!”

He gasps, whirling on his heel. “Stakar?” he whispers, not daring to believe it.

“Yondu! Where are you? Yondu, answer me!”

It’s not his imagination. “Stakar?” he yells, turning towards the voice. “Stakar!”

“Yondu?” There’s the sound of someone crashing through the underbrush, and suddenly Stakar is there, about a hundred meters away. They both stop, staring at one another. “Yondu!” Stakar yells, and tears towards him. Before Yondu can react, the Ravager Captain has seized him in a one-armed hug, slapping his back. “Thank gods you’re all right.” He releases him quickly, knowing that Yondu still isn’t used to affectionate physical contact. He takes him by the shoulders and gives him one sound shake. “Don’t you run off like that again, boy! We were worried sick.”

Yondu’s eyes widen. He can’t believe his ears. “Ya – ya were?”

“Of course we were,” Stakar says earnestly. “When we couldn’t find ya, we all started lookin’ for ya everywhere. Oh, speakin’ of which.” He presses a button on his wrist com. “Aleta, come in.”

“Did you find him?” Her voice snaps. “‘Cause if you didn’t and you’re wasting breath to-”

“I found him. Say hi, boy.”

“Hi Aleta,” Yondu says, a little tentatively, leaning towards Stakar’s wrist.

“Yondu!”There’s a nearly-imperceptible sigh of relief in her rough voice. “Are you hurt?”

“No ma’am,” he answers.

“Thank all the gods,” she replies in a murmur they barely catch. “I’ll round up the team, Stakar. Just get our boy back on board.”

“Copy that.” Stakar slings an arm around Yondu’s shoulders. “Let’s get you home, son.”

Later that evening, Yondu is sitting awake, seated against the wall, watching his crew mates as they sleep. Stakar rolls over towards him, and Yondu is surprised to see he too is awake. They catch each other’s eyes, and Stakar quietly gets up, seating himself next to Yondu.

“Ya okay, boy?” the Captain asks. “Why ain’t you sleepin’?”

“M’ fine. Jus’ thinkin’.” Yondu replies.

Stakar nods. After a few minutes of silence, he turns to him again. “Can I ask ya something?”

“Yer the Cap’n, ya can ask me anythin’ ya want.”

Stakar chuckles quietly, then asks, “Down on the planet - when I said we were worried about ya, ya seemed surprised. Why was that?”

Yondu offers a shrug of one shoulder and fiddles with a loose thread on his pant leg. “Guess no one’s ever been worried ‘bout me before.”

Stakar falls silent, and Yondu is worried he might have said the wrong thing. He looks up into the Captain’s eyes and sees something he wasn’t expecting – sadness. Without a word, Stakar’s arms wind around him, pulling him into an embrace.

For the first time he can remember, Yondu doesn’t want to escape it. They didn’t leave me. They didn’t want me gone. They came to find me. They want me here. I ain’t worthless, not to them. He curls his fingers into Stakar’s shirt, pressing his head into the older man’s shoulder. It feels right, somehow.

He feels Stakar hand cradle the back of his head, and his quiet voice a moment later near his ear. “Yondu,” he says, “You are part of this family, I want you to understand that. And as family, you will never be left behind. I promise.”

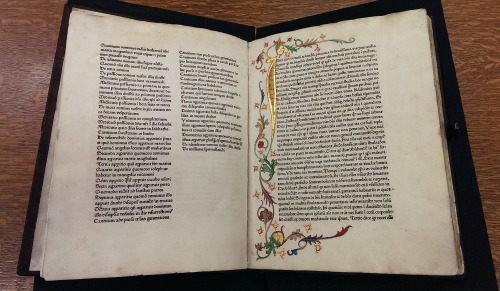

One way to measure the popularity of a given text is to count the number of times it’s been published. For example, the immense popularity of The Imitation of Christ, which went through 78 editions in the 15th century, has been said to trail only the popularity of the bible itself as a devotional text. Compare these to 15 editions of Dante’s Divine Comedy in the 15th century and one can begin to appreciate just how popular Christian devotional literature once was. As it happens, MSU has one of just eight known copies of a rare 1495 editionofThe Imitation of Christ.

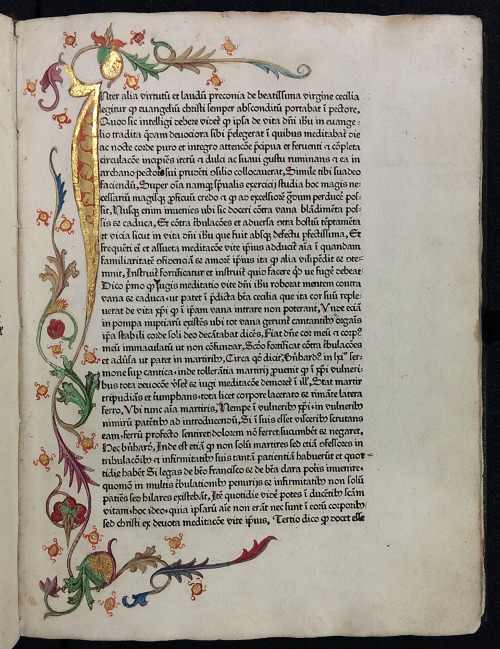

Not far behind the popularity of The Imitation of Christ, with at least 65 editions appearing in the 15th century, is the Meditations on the Life of Christ. MSU is very fortunate to have recently acquired the first printed edition of the Meditations—the very first of those many editions to appear in the 15th century (pictured above). Published in 1468, this edition has the distinction of being the first dated book printed in the city of Augsburg—and this at a time when fewer than a dozen cities in all of Europe had the technology to print books. This first appearance in print is a fine complement to our medieval manuscript of the text, and it also claims the honor of being one of the three oldest printed books to reside in Michigan.

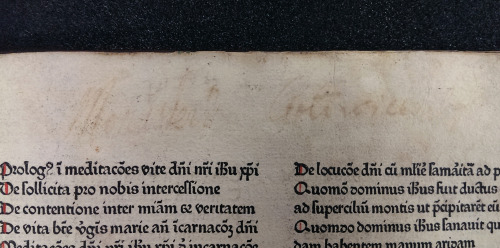

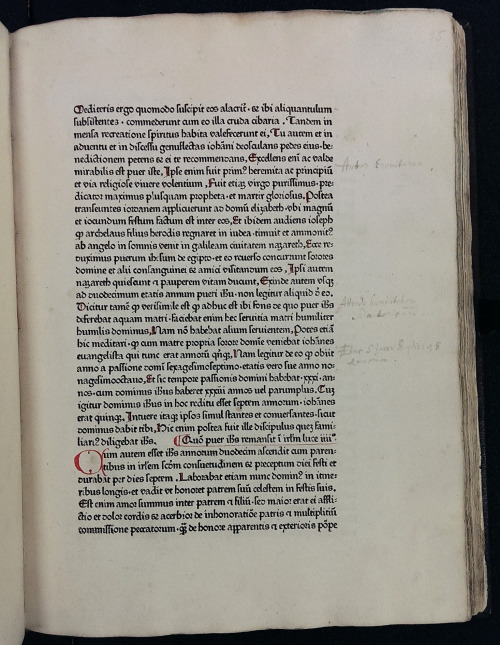

On the front paste-down of our Meditations, afloat in a sea of booksellers’ annotations, is the bookplate of Hieronymus Baumgartner (1498-1565), a powerful advocate of the Protestant Reformation. Baumgartner enrolled at the University of Wittenberg in 1518, the very town in which just a year earlier Martin Luther allegedly nailed his Ninety-five Theses to a church door. In Wittenberg, Baumgartner befriended prominent reformers Philipp Melanchthon, Georg Major, and Joachim Camerarius, and he later helped found the Melanchthon Gymnasium in his hometown of Nuremberg in 1526. Baumgartner was an accomplished statesman, to be sure, but we’re particularly pleased because his bookplate, as far as we can tell, is the oldest bookplate in MSU’s collection.

~Pat

This Provenance Project guest post was written by Patrick Olson, Rare Books Librarian at Michigan State University Special Collections.

Post link

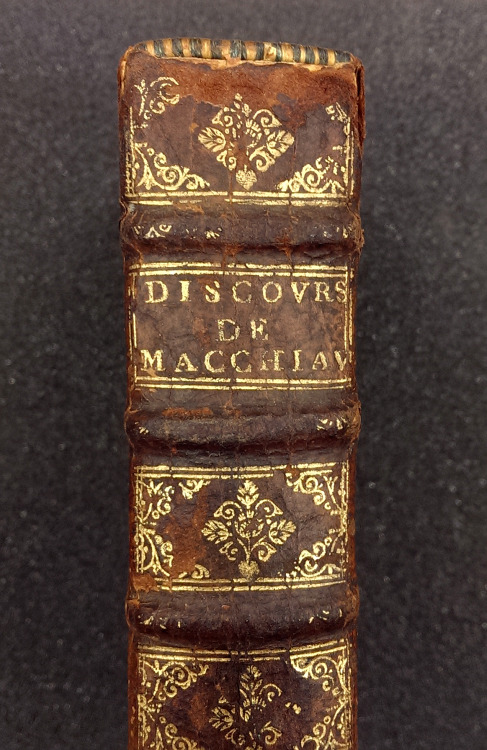

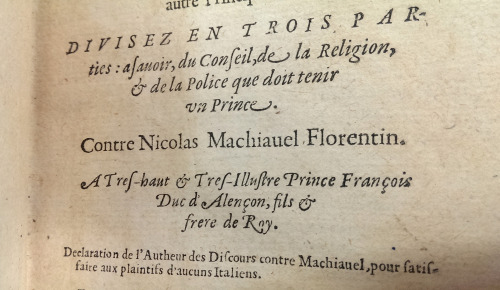

In preparing for the purchase of another title by the Italian Renaissance philosopher, Niccolo Machiavelli, I found this sixteenth century rebuttal of the principles of Machiavelli by the French jurist Gentillet.

In his book, Discours sur les moyens de bien gouverner, Gentillet analyzes the character of a ruler, rights of parliament, and capacity of councilors among other traits of good statecraft. It is landmark book and quite uncommon, but what struck my eye immediately was the term “CONTREMACH:” boldly written on the top of the text block. At first glance I thought an owner of the book used the term for shelving purposes, but why write such an aid on the top of the text block where it is not readily seen? And more importantly, what does “contremach” mean?

After showing this to Andrew Lundeen, founder of the MSU Provenance Project, he quickly determined that the term “contremach” is really an abbreviated reference to the title (or shorthand name) of the work and was likely used for shelving purposes. That is to say, CONTREMACH:orCONTRE MACH: stands for “Contre [Against] Mach[iavelli].”

~Peter

This Provenance Project guest post was written by Peter Berg, Head of Special Collections and Associate Director for Special Collections & Preservation at Michigan State University.

——————–

Andrew’s note: This fascinating little volume illustrates a couple of interesting facts about working with old books. Firstly, we should never assume that a work only went by one title, or even that the full printed title of a book was the preferred nomenclature. Formal titles were often absurdly long-winded, and so abbreviated titles or referential names were frequently used in their place. This particular copy of Gentillet’s work, for example, bears three different names on the item itself: “Discours sur les moyens [etc.]…” on the printed title page, “Discours de Macchiav[elli]” on the spine, and “Contremach” or “Contre Mach” on the top edge of the text block (the abbreviation is taken from a portion of the work’s subtitle: “ContreNicolasMachiauel Florentin”).

This confusion about how to “properly” refer to the work can be seen in the various names of reprints and later editions as well. Here at MSU we have several versions of this work cataloged under different titles:

Discovrs svr les moyens [etc.]… — With the name copied directly from the title page of this 1579 printing (inc. the archaic use of “V”s for “U”s)

Discours contre Machiavel — The title of this 1974 updated edition

And finally, Anti-Machiavel — A 1968 printing that uses a historically common shorthand title for the work, one very similar to our CONTREMACH edgemark

Secondly, the placement of our CONTREMACH title indicates that this book may not have always been shelved in the way most modern readers and library-goers are familiar with—upright with its spine facing outward. The use of edge-marks such as this, as well as historical depictions of book collections in art, show that books were often stacked on top of one another with the edges of their text blocks visible.

Post link

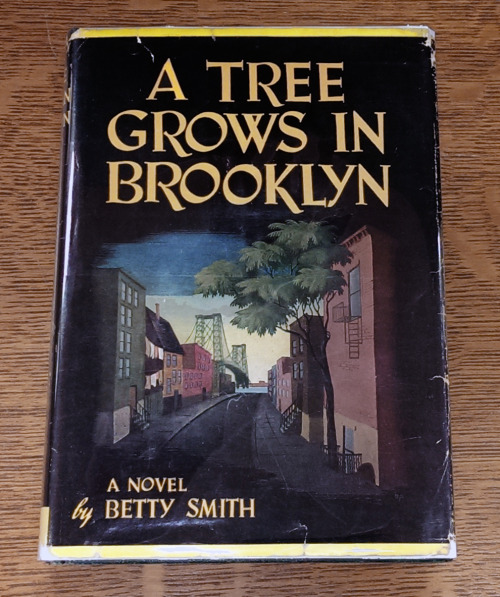

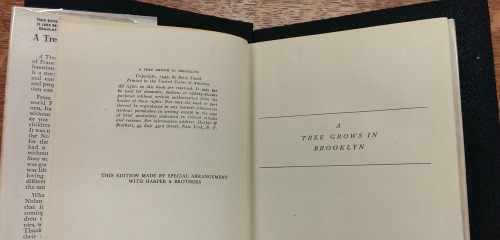

As part of our initiative to collect the first or earliest possible edition of books cited in the Library of Congress “Books That Shaped America” list, we recently acquired two books on the list that are worthy of recognition in our Provenance Project.

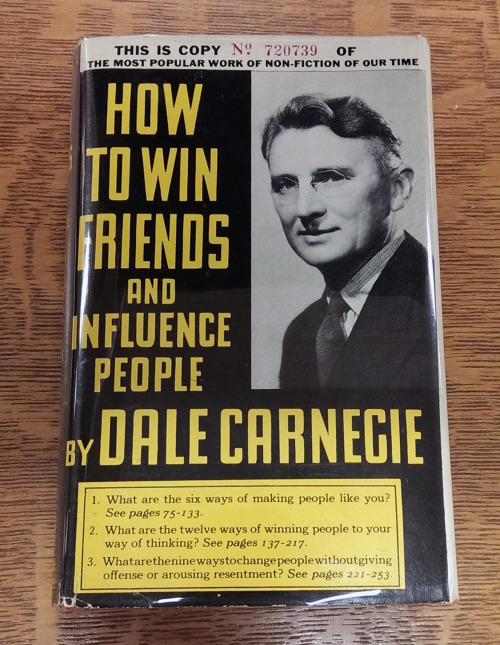

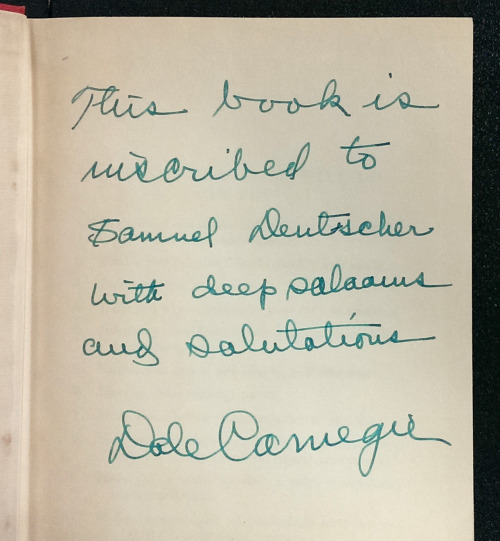

One acquisition is a first edition of A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, which features the autograph of the author, Betty Smith, while the second book is a later printing of a first edition of How to Win Friends and Influence People. In it, the author Dale Carnegie provides a lengthy inscription on the front endpaper:

This book is inscribed to Samuel Deutscher with deep salaams and salutations

Dale Carnegie

The book—which is considered the grand-daddy of all self-help books—sold over 15 million copies, and while we’re confident that our readers are already enthusiastic book lovers, perhaps we’ll study Carnegie’s principles to make our audience feel even more “important and appreciated.”

~Peter

This Provenance Project guest post was written by Peter Berg, Head of Special Collections and Associate Director for Special Collections & Preservation at Michigan State University. Dr. Berg received his undergraduate degree in History from MSU in 1969, his Library Science degree from the University of Michigan in 1975, and his doctorate in History from MSU in 1994.

Post link

By Tochi Onyebuchi

I was asked recently on a panel what my thoughts were regarding the idea of a black Superman. There was a brief flutter of confusion on the panel, as I and another panelist wondered if some bit of casting news swept us by, but we soon realized the question was more theoretical than anything else. Questions about race and casting and storytelling generally are.

If I recall correctly, my answer was a bit of a deflection. I’d asked the questioner and the audience to, instead of engaging with a non-white Superman, ask themselves why Superman had been made white to begin with. This all-powerful demi-god, who could leap tall buildings in a single bound and who possessed untold amounts of strength, why, if he could already do so many things, was he also made white?

Increasing diversity in storytelling often comes with the built-in assumption that it is writers of color or disabled writers or non-binary writers who are doing the work. These people telling their own stories. The idea is that, the more these stories make it into the marketplace, the more a reader’s eyes will be opened to human possibility, the more likely they are, when they see a person of color or a disabled writer or a non-binary writer, to act with humaneness, rather than hatred. A story from a black author about a black boy makes its way into the hands of a young white reader and, suddenly, the pathway to bigotry is blocked by the empathetic undertaking that is the reading of a book.

But this is supposed to be a group project.

For me, sometimes what increasing diversity in storytelling entails is simply imagining ourselves outside of what we usually see. This can mean black superheroes and female corporate moguls, but it can’t be simple race- or gender-swapping. If the character is not a heterosexual, cis-gendered, white male, let’s make sure they are a fully realized character whose non-whiteness, for instance, isn’t just a splash of paint from an errant paintbrush. When I think back to that question about Superman, I find myself wishing from time to time that I’d answered along these lines, that I’d challenged the audience to imagine what it would look like in 2018 for a black man in America to be able to deflect bullets.

As powerful and as necessary as #ownvoices stories are, I can’t quite let white authors off the hook. In my estimation, it is not enough for them to sit back while the rest of us launch ourselves forward, telling stories that should have already been told, making up for lost time. I think white writers, male writers, should be called upon to interrogate their privilege, and to do so publicly and to do it in their storytelling. For so long, our heroes have looked a particular color. They should ask why, and they should ask it loudly.

Which brings me back to Superman. In many ways, this undocumented immigrant is the embodiment of white, male privilege. No mountain can stop him from getting where he needs to go. People around him are mosquitoes he can flick away with a finger. And, as Clark Kent, he wears glasses he doesn’t even truly need, a fashion accessory more than a health necessity. Of all the forms this alien could have chosen, he chose white. And I think all of us should be asking why.

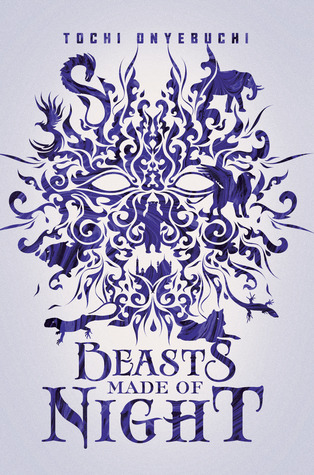

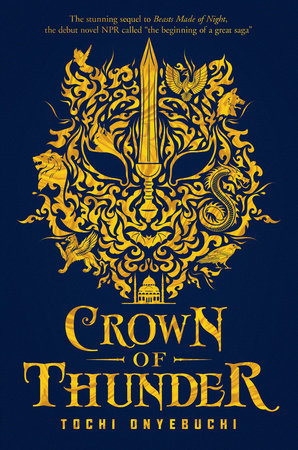

I wrote Beasts Made of NightandCrown of Thunder not only to imagine a kid the same color as me saving the world, but also to imagine him fighting the awesome anime battles I watched as a teen and being the object of someone’s affection. I wanted to see a black boy fight monsters and be flirted with.

I talk at length about what it can mean, in a cosmic sense, having a hero of color in a world drawn from a non-Western mythos; the implications for diversity; my hopes with my readership. But lost in all of that is this selfish desire I’d had at the very beginning: I’d written Taj’s story for myself as much as for anyone else. Taj wasn’t just a black protagonist. He had my insecurities and my youthful bravado and my halting attempts at caring for my younger siblings. An undercurrent to a lot of questions I get is why did you make Taj black? which is a funny way of saying why did I make Taj me?

Because skin is everything that comes with it. Color carries the context of lived experience.

I don’t ascribe to any “color-blindness” that isn’t diagnosed by a doctor. Someone may insist that it shouldn’t matter what color our heroes are, but I disagree. It does matter. Because skin color has context. It informs our symbols, such that bullets bouncing off the chest of a black man make an entirely different sound than they do bouncing off the chest of a white man, even if the difference is pitched at a frequency only some of us can hear.

Tochi Onyebuchi’s fiction has appeared Asimov’s, Obsidian, and Omenana and is forthcoming from Tor.com, Harper Collins, and Razorbill. His non-fiction has appeared in Nowhere Magazine, the Oxford University Press blog, Tor.com, and the Harvard Journal of African American Public Policy, among other places. His Nommo Award-winning debut young adult novel, Beasts Made of Night, was published by Razorbill in Oct. 2017. Its sequel, Crown of Thunder, was released in Oct. 2018.

His books are available for purchase.

Historical fiction has always fascinated me. As a young reader, I remember sitting on a cushy winged-chair in a quiet, sunlit corner of the Eagle Pass Public Library getting lost in books about other times, other cultures. I was mesmerized by the period details, but more than that I was drawn to the fiery hearts of passionate characters who fought fiercely to save themselves in times of great strife.

Torches, lamps, roaring flames, these things are often found in historical fiction. They are the staple of books on revolution and change. But they are also things I came to associate with truth and passion. They were metaphorical representations of courage and conviction in the books I read, books that fanned the flame of my development as a writer who attempts to write to elucidate.

ALL THE STARS DENIED is a companion novel to Shame the Stars (Tu Books, 2016). It is the second installment in the family saga of the del Toros as they continue to struggle and flourish despite racism, prejudice, and other political adversities in the United States. In this stand-alone book we meet Estrella, the eldest daughter of Joaquín and Dulceña del Toro (the protagonists from Shame the Stars). The year is 1931, and the Great Depression has brought about racial segregation in Monteseco and even more derision towards Mexican nationals living and working in the United States.

When Estrella organizes a march against the ill treatment of mexicanos in her divided town, she and her family are targeted and forcibly “repatriated” to Mexico. In one torch-lit sweep of Rancho Las Moras, Estrella loses her home, her citizenship, and her father.

The trials and tribulations Estrella and her mother, Dulceña, face as they attempt to return home to Texas with her little brother, Wicho, illustrates another difficult time for Mexican Americans in this country, for it is a matter of historical fact that in the 1930’s the U.S. and Mexican governments worked together to repatriate over 1 million Mexicans & Mexican-Americans back to Mexico. It is also a sad fact that 600, 000 of these repatriates were born U.S. citizens.

Although I did a lot of research on the subject of repatriation during the 1930’s, I had to find ways of incorporating those facts effectively into the novel, and that’s where the art of fictionalizing historical events came into play.

I took inspiration from the books and articles I read as well as the first-person accounts of interviews on YouTube. The small mention of two thousand repatriates huddled together in the winter of 1931 in a corral behind the customs house in Ciudad Juárez in Francisco E. Balderrama’s 2006 book, Decade of Betrayal: Mexican Repatriation in the1930s, outraged me, and I knew that the incident needed to become a scene in my novel. But I had no details of that occurrence, so I had to put myself in that position, envision the environment, craft the scenes, and give voice to the characters as best I could. I had to recreateit if I was going to bring the injustice of it all to light.

Throughout the creative process, I asked myself some hard questions. What is important here? Why do I need to depict thisor that incident? At the heart of it all was my need to tell the truth intertwined with my frustration at the inhumane treatment of mexicanos and the demoralization of an entire group of people—mi gente.

Whatever else may fuel my writing in years to come, I know this one thing to be true: I will always write with passion. I will play with fire. I owe it to my loved ones!

Guadalupe García McCall is the author of Under the Mesquite (Lee and Low Books, 20111), a novel in verse, which received the prestigious Pura Belpre Author Award, was a William C. Morris Finalist, and was included in Kirkus Review’s Best Teen Books of 2011, among many other accolades. Her second novel,Summer of the Mariposas (Tu Books, 2012), won a Westchester Young Adult Fiction award and was a finalist for the Andre Norton Award for Young Adult Science Fiction and Fantasy. Her third novel, Shame the Stars (Tu Books, 2016), is a Commended Title for the América’s Book Award and was chosen as Texas’ Great Reads by the Center for the Book in affiliation with Texas State Library and Archives Commission. Her 4th novel, All the Stars Denied, was just released from Tu Books this fall and has already received a School Library Journal starred review. She is an Assistant Professor at George Fox University and lives with her husband in the Pacific Northwest.

All the Stars Denied is available for purchase.

In graduate school, we had an epic battle over characters’ racial diversity/representation on the page, and craft. Some well-meaning white writers in workshop were including problematic depictions of characters of color in their stories – the “all-seeing,” “magical” black woman, the homeless black man, the perpetual Asian American foreigner. When confronted, I remember that one particularly irascible, intractable white male peer accused us of policing art. “You can write about whatever you want, however you want,” he sputtered. “If I want to write about a triangle on the moon, I should be able to do it. And no one should criticize me for not including black people.” I remember I smiled wryly and said, “Yes, but that doesn’t mean that it will be good art. If you are using problematic and tired racial stereotypes and tropes in your writing, or just writing a flat universe of (white, male, middle-class) characters it doesn’t matter how awesome your triangles on the moon might be: your form is probably pretty lazy, too.”

Needless to say, he didn’t exactly appreciate my commentary.

It did, however, force us to confront the relationship between diversity of content, and diversity of form – a topic which I thought I’d pose in this blog post. Quite simply, I’m interested in this question: Does more racial/identity diversity of characters and content necessarily mean more formal diversity? Meaning, are stories that include characters from a variety of racial, ethnic, class, gender, and other identities more likelyto be better written stories, or take more formal risks, or be more formally interesting, than stories with characters with mainstream (read: white) backgrounds? In the course of writing my new book, Dream Country,I certainly found this to be true.

Dream Countryis a sprawling story of colonialism, war, family, and home, and features five narrators on two continents, over 200 years. There was no way to write this novel and do the questions it asks justice without pushing myself out of my formal comfort zone. It could not be your standard one-voice YA novel (not that there is anything wrong with that – my first novel, See No Color, is a YA novel of this variety. But this approach just was not going to work for this particular project). I needed to inhabit the voice of a disaffected teenage Liberian refugee, a 19thcentury African American single mother, a young Liberian revolutionary in Monrovia in 1980, and a modern-day young, queer, African and American writer. I needed all these voices to be distinct, yet compelling, and I needed them to also somehow fit together in the contours of a larger story. Needless to say, my content comfort zone was also deeply challenged in the writing of the book. I am not Liberian, but African American, and balked at the prospect – and responsibility – of representing Liberians on the page. But I realized that this was actually the topic of the novel itself: The chasms and connections between Liberians, Liberian Americans, and African Americans. In my quest to tell this story, I had to attempt to cross these chasms by doing intensive bibliographic and interpersonal research. I read everything I could get my hands on about the colonial period in Liberia; went to Monrovia and interviewed government officials and everyday people about the 1980 coup; and interviewed two gentleman who were generous enough to share their stories of being “sent back” to Liberia from the U.S. by their parents, in their eyes, to save their lives. While I am quite sure that there are still plenty of errors in the book, its formal challenges required me to reach for a new level of excellence in its content – a phenomenon I think may be more common than we realize.

Shannon Gibney is a writer, educator, activist, and the author of See No Color (Carolrhoda Lab, 2015), a young adult novel that won the 2016 Minnesota Book Award in Young Peoples’ Literature. Gibney is faculty in English at Minneapolis Community and Technical College, where she teaches critical and creative writing, journalism, and African Diasporic topics. A Bush Artist and McKnight Writing Fellow, her new novel, Dream Country, is about more than five generations of an African descended family, crisscrossing the Atlantic both voluntarily and involuntarily (Dutton, 2018).

Dream Country is available for purchase.

Where do you find your story ideas? It’s a question I’m asked from time to time, and the answer is always the same; I find them everywhere. In history books and old newspapers. On walks around the neighborhood and travel farther afield. By sitting in parks and restaurants and watching the world unfold around me. Really, everywhere. My books are made up of whatever happens to fascinate me at the time I’m writing them.

For my debut, A Death-Struck Year, those things were plague, architecture, and the State of Oregon. An odd trio, but I found an editor who was game, and in the end the description went something like this: When the Spanish influenza epidemic reaches Portland, Oregon in 1918, seventeen-year-old Cleo leaves behind the comfort of her boarding school to work for the American Red Cross.

My second book, Isle of Blood and Stone, is the story of a royal mapmaker, nineteen-year old Elias, who discovers a riddle hidden in the borders of an old map. My interests had shifted, to mapmakers, mysteries, and islands. Mapmakers because I had just finished a book on the Lewis and Clark expedition, one that made me want to learn everything I could about the early days of world exploration. Mysteries because it’s a genre I love, and I like to write what I read. And islands because my mother had died recently, and I found my thoughts turning, with increasing frequency, toward home.

I grew up on a tiny island in the Pacific. If you were to look at any world map, you’d have a hard time finding Guam. But it’s there, halfway between Australia and Japan. It’s a wonderful place to be a kid. I learned to swim in its beaches, to roller skate down the sidewalks in my village, and my earliest memories are of shave ice and seafood and plumeria trees everywhere I looked.

If you were to thumb through a copy of Isle of Blood and Stone, you would see the requisite fantasy map near the front-the island kingdom of St. John del Mar. A fictional island, but anyone familiar with Guam will recognize its distinct shape. There are other, more subtle, inclusions. The Sea of Magdalen is named for my mom, Maggie. Del Mar’s Marinus Road is a nod to Guam’s main thoroughfare, Marine Drive. The harmless water snakes I swam with as a child are turned into monstrous sea serpents. What else? A forest inspired by an old legend, a young explorer named after a favorite cousin (sorry other cousins!). And though Elias’ relatives wear fancy medieval clothing, I gave them characteristics I could relate to. They’re loud, loving, nosy, the kind of relatives who always know more than you want them to.

There will be other books, if I’m lucky. Other stories, other interests. But not a book like Isle, one that walks me back through the years to my childhood and reminds me of home. This is a once in a lifetime story, and I’m very happy I have a chance to tell it.

Makiia Lucier grew up on the Pacific island of Guam and has degrees in journalism and library science from the University of Oregon and the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. She is the author of A Death-Struck YearandIsle of Blood and Stone, described as “a brilliant fantasy” by Booklist. She lives in North Carolina with her family. You can visit her at makiialucier.com or on Twitter: @makiialucier.

Isle of Blood and Stone is available for purchase.

Growing up male in America, there were many damaging things I learned about being a man. Society taught me some of these things explicitly, while others were implicitly made clear through potential consequences that were a constant threatening undercurrent. The one I want to discuss here is the one I find myself thinking about a lot these days as a high school teacher and a writer of fiction for young adults: the lie that boys do not feel deeply, that we are simply hard-wired to be insensitive.

Society constantly bombarded me with this lie even as I knew it wasn’t true. As a kid, I cried easily. I enjoyed poetry and reading. I loved cuddling stuffed animals. I felt bonded to pretty much any living thing I came across (or even any inanimate object if given a name). But as I grew older, I received the message loud and clear that these were not aspects of myself I should embrace publicly, or I would be labeled as “gay” or a “pussy” and then suffer the social consequences. Of course, as a kid I didn’t have the ability to deconstruct the homophobia and misogyny inherent to this limiting view of masculinity and the wider damage caused by buying into it. I didn’t have the self-esteem to be my actual self. Instead, I downplayed all of those “softer” sides. I learned to stop crying, to hide my stuffed animals, to avoid emotions outside of humor and anger. I emphasized the sports I played and the girls I wanted to get with. So it was not that as a male I did not feel things deeply, but that I became an expert of suppression.

As a result, I never lacked for friends, which I suppose was the point of conforming. But, even so, I was always lonely. I never felt very close to any of the guys I hung out with in my middle school or high school years no matter the quantity of time we spent together. I believe they were also buying into the same lie as me—a lie even more strongly messaged to boys of color—so there was this collective unspoken agreement to never talk about anything too real, anything that would expose our softness. Instead, we played—sports, video games, music, etc.—because to play was to distract ourselves, to make us believe our friendship was deeper than it was. Yet I always wondered how many of us were secretly lonely, how many of us dealt with that loneliness in damaging ways.

I think this is why when I write YA fiction, I gravitate toward exploring friendship among boys, and particularly boys of color. This is why my characters are, at their core, lonely. After the Shot Dropsbegins with Bunny and Nasir each in isolation, struggling with the fallout of Bunny’s decision to transfer schools. Their issues are grounded in this loneliness, and it seems so obvious that they could resolve their problems if only they knew how to communicate honestly, to be vulnerable with each other. But the challenge here as a writer of realistic fiction is the challenge of real life: how do they overcome all of the societal programming that pressures them to do the exact opposite?

As many writers of children’s literature, I believe that fiction can serve as a roadmap. It can be countercultural, can be a form of resistance that shows readers another way to exist. A better way, a more freeing way. That is what I hoped I have done with Nasir and Bunny, and it’s what I hope to do with my other stories as well. I consider myself lucky to be writing at a time when so much of what I’ve struggled with in silence is now part of the national conversation, and I’m proud to be writing alongside so many other young adult authors who are trying to dismantle these toxic ideas. InThe Fire Next Time, James Baldwin writes, “Love takes off the masks we fear we cannot live without and know we cannot live within.” I am hopeful that these stories will help our boys figure out how to remove their masks in order to construct a healthier masculinity.

Randy Ribay is the author of An Infinite Number of Parallel UniversesandAfter the Shot Drops. He was born in the Philippines and raised in the Midwest. A graduate of the University of Colorado and the Harvard Graduate School of Education, he is a high school English teacher in the San Francisco Bay Area where he lives with his wife and two dog-children.

After the Shot Drops is available for purchase.

I was six years old when I learned that I had an older brother I would never meet. Growing up in a slightly traditional Chinese family, we’re not used to expressing emotions and feelings. But it was clear that my mother’s miscarriage had cast a pall over the family, even when it went unspoken. My parents had been looking forward to having a baby boy, and on the rare moments when that topic came up (often unexpectedly) in conversation, I could sense that quiet sadness that never went away.

I was in my teens before I realized that I—or my father, or the both of us without either side acknowledging—might have started compensating for that absence. I was always tomboyish, and I gravitated to action figures, martial arts, and rough sports. I’d always been the daddy’s girl. My father was an award-winning basketball coach, and while basketball initially didn’t strike my fancy I joined basketball camps that he helped oversee and and practiced mainly to spend more time with him. We had similar interests in pop culture and the like, so we were quick to bond over them - he taught me how to speak Klingon, bought me my first light saber, played video games together.

It wasn’t until I was much older that I realized that these were easily things he could have done with my older brother or—what would probably have happened—things we both could have done with my older brother. I’ve heard of other Chinese parents, fathers in particular, who resent not having a son and often take that frustration out on their families. To his credit, my father never did any of that. But I could see his wistfulness when he played with some of my younger cousins, singling out one of them in particular to constantly tease and play pranks on (jokes and humor were his chosen method of expressing affection), or on those rare occasions when anyone ever alluded to my older brother. I saw it most clearly in his unabashed happiness when I told him he was going to have a grandson, and when he nearly broke down when Ezio was born.

It was when I was pregnant that I started thinking about that brother more often than I ever had in the past, (brought back to the fore most recently, since my little Ezio is about to have a new sibling as well). I had just finished The Suffering, the sequel to the Girl from the Well, and while I’d taken a few months off from writing to prepare for a toddler I’d also been at a loss over what to write next. Somewhere during those sleepless nights where I had to wake every couple of hours to feed my baby or pump, I started coming back to that. My brother didn’t even get to have a name, and it felt wrong for him not to have one. I thought about giving him one, thought about Chinese mythology where spirits could come back from the dead—not to haunt and terrorize like Western urban legends, but sometimes to comfort and impart knowledge.

In Chinese lore, they sometimes came back as fox spirits.

Chinese spirits were also transcendent, intelligent specters—in many stories they show themselves to philosophers while the latter meditate or study; sometimes they even take tea with them.

So I started writing about a girl named Tea and a brother she brought back from the dead, named Fox.

The Bone Witch is a lot of things - a ghost story, a warning about how absolute power can go wrong, a coming of age story, a vengeance quest, a magic tale, a treatise about the patriarchy and how even well-meaning matriarchies can get things wrong.

But at its heart, in its truest, purest form of heartsglass, is just a story about a girl and her brother.

The Bone Witch is about learning to live together, about what it’s like to be family.

The Heart Forger is about learning to make choices beyond that family, to be independent while still learning to give each other space, about learning to maintain that love despite change.

And the Shadowglass, due out next year, will be about learning how to say goodbye.

And I think it’s the best eulogy about my brother that I’ve ever written.

Despite an unsettling resemblance to Japanese revenants, Rin always maintains her sense of hummus. Born and raised in Manila, Philippines, she keeps four pets: a dog, two birds, and a husband. Dances like the neighbors are watching.

She is represented by Rebecca Podos of the Helen Rees Agency.

The Bone Witch and The Heart Forger are available for purchase.

By Sam J. Miller

When Our Stories are Ugly

#ownvoices as a weapon against internalized oppression

When I started to tell my story, I knew that there would be trouble.

Months before my debut novel The Art of Starving came out, people were upset about it. They saw the synopsis and said it romanticized eating disorders. My protagonist, Matt, is a bullied small-town gay boy with an eating disorder (all of which I was) who believes that starving himself awakened latent supernatural abilities.

Eating disorder superpowers? Yeah, I get how that sounds problematic.

But the fact is, that was my experience. I didn’t get superpowers, but my eating disorder made me feel powerful. In control of something. I had absorbed so much hate and fear and toxic masculinity that they were the only weapons I had. And when the demons came - and they came every day - they were what I had to work with.

This is not an uncommon response. Many other survivors I’ve spoken with have shared a similar experience. I get emails all the time, from eating disorder survivors who have read the book and felt validated for the first time.

#ownvoices can get ugly, because our stories can be ugly. It isn’t all pride and power. And the pride and the power, if we’re fortunate enough to arrive at them, come from the ugliness. From what we’ve been through. From our ability to survive.

When we tell the truth about who we are and what we’ve been through, not everyone will like it. Adults may think that young people need to be shielded from these ugly truths, as if hiding from horror will make it disappear. Angie C. Thomas’s brilliant The Hate U Give was just banned in a Texas school district, allegedly for sexual content - when there is literally zero sex in the book - when obviously what they were really upset about was how brilliantly the book brought to life the pain and power of a young Black woman fighting back against police brutality. And young people, even ones from our own communities, might prefer not to explore these issues up close. Especially if they’ve been through something similar. They might find these discussions triggering. I have tons of love and support and respect for eating disorder survivors and others struggling with body image issues, who have to take a step back from this book. I have less respect for the grown-up gatekeepers who think that the way to help young people survive into adulthood is to pretend their pain does not exist.

My protagonist, Matt, is damaged. He’s been traumatized by constant physical and emotional abuse, and the crippling impact of patriarchy. He’s full of hate and anger and shame. He’s also smart and funny and full of love. We’re complicated people - all of us. Like Matt, I had internalized so much toxic masculinity - even as I rejected heteronormativity and embraced my queerness - that my rage took the form of violence. And when I couldn’t turn it on others, I turned it on myself.

Queer youth are especially susceptible to having complicated and painful body image issues, because we often grow up in a space where there is nobody to tell us we’re beautiful, nobody to fall in love with our minds. We’re having crushes on people that are not reciprocated. We’re being made to feel ugly and awkward and unwanted. That can be crippling. Some of these issues can last a long time. And then you grow up and enter a broader gay culture which is just as obsessed with a certain idea of masculinity and a certain type of body.

The power of #ownvoices stories to challenge is massive. With The Art of Starving, I wanted to confront the stigma and shame that so many young queer people are living with. I wanted to tell them how awesome they are. How I was there, once, sunk deep in misery and suicidal ideation and (sometimes) bloodthirsty rage, and eventually came out the other end of it being proud and happy and thanking the gods every day that they made me gay. But if someone had told me that then, I wouldn’t have believed them. I’d have assumed they were like every other adult, a complete idiot who didn’t understand me and therefore had nothing to teach me.

So when I started to tell this story, I knew that I had to honor the darkness that many young people experience. I get that some people won’t want to deal with it.. But it would have been dishonest of me to say “you’re awesome!” without acknowledging the pain folks feel.

If there’s a message to my book, it’s this: You are beautiful, you are magnificent, no matter what you look like. And if you are having complicated feelings about who you are and what you look like and what people think of you, that’s not weird or unheard of. Respect the darkness, but know that you are so much more.

Sam J. Miller is a writer and a community organizer. His debut novel The Art of Starving (YA/SF) was published by HarperCollins in 2017, and will be followed by Blackfish City from Ecco Press in 2018. His stories have been nominated for the Nebula, World Fantasy, and Theodore Sturgeon Awards, and have appeared in over a dozen “year’s best” anthologies. He’s a graduate of the Clarion Science Fiction & Fantasy Writers Workshop, and a winner of the Shirley Jackson Award. He lives in New York City, and atwww.samjmiller.com

The Art of Starving is available for purchase.

By Sarah Raughley

You know, it’s always cool to read letters from fans of the Effigies series who really appreciate the fact that the titular Effigies are from a racially diverse background—Maia being of mixed Jamaican—American descent, Chae Rin being Korean Canadian, Lake being Nigerian-British and Belle being French. For me it was very important to have the Effigies be as global as the story. This is a world, after all, where any girl in the world could potentially become an Effigy. It wouldn’t make sense, then, for the characters to be an all-white band. When I’m able to do events with kids in the community, for example A Room of Your Own in Toronto where I talked with girls of color at the public library, it’s just phenomenal to see with your own beady little authorly eyes just how important writing diversity is.

And it’s weird because I’ve been told so many times by certain people that there must be a point to the diversity in your book, which I think for them means that your characters’ non-whiteness must be the crux of the story, the world building and/or the characters’ own personal arc. My personal approach to racial diversity is a little different. Of course, our backgrounds inflect who we are in many ways and gives us experiences that others may not have had. However, for my characters, rather than thinking of them as Korean first, or black first, or white first, I think of them as characters first. That means understanding that despite what differences we may have depending on what our ethnicity or nationality is, what makes us human is fundamentally the same. We are all driven by feelings, fears and desires that shape who we are as people. The fact, for example, that I’m Nigerian Canadian doesn’t mean that I somehow respond radically different than someone else when I am in pain or confused or scared for my life, nor does it mean that I’ll react exactly like another Nigerian or Nigerian Canadian would. Certainly, there are cultural behaviors that are learned when you grow up in certain cultural environments, but ultimately, the simple fact of one’s racial makeup cannot be the determining factor of how we act and who we are. Though some would want you to think otherwise, we as human beings have far more in common with each other than with any other species; certainly, regardless of our skin tone or nationality, we have far more similarities than differences.

For me, writing diversity means understanding that cultures and ethnicities are not a monolith. I am not like every other Nigerian or every other Nigerian Canadian or every other diasporic Nigerian living on this planet. I have my own personality, my own presence, my own voice (fun fact, I’ve been told over the phone that I sound like a white girl, which is a lot to unpack) based on how and where I grew up, based on my experiences, and everything else that goes into making someone an individual. If human beings can’t be pigeonholed into certain molds of personality, voice, and behavior based on their ethnic makeup, then neither can (and neither should) characters.

So while diversity is important, one crucial aspect of diversity in books is not approaching it with stereotypical, preconceived notions for how certain characters of a certain race are supposed to act, sound etc. In Fate of Flames and Siege of Shadows, the ethnicities and nationalities of the characters are part of who they are; but as a reader, what you’ll see before their ethnicity is what I always intended for you to see:

Their humanity.

Sarah Raughley grew up in Southern Ontario writing stories about freakish little girls with powers because she secretly wanted to be one. She is a huge fangirl of anything from manga to SF/F TV to Japanese role playing games. On top of being a YA writer, Sarah has a PhD in English, which makes her doctor, so it turns out she didn’t have to go to medical school after all.

Siege of Shadows is available for purchase.

My graphic novel Spinning has been out now for over a month. I think. It’s actually a little hard to remember. Other authors may relate to this feeling - before your book is published, it feels like it’s never going to come out and the world is acting against you. And then when it finally comes out, it feels like its been there forever.

I’ve been traveling around with Spinning, talking to classes full of fidgeting kids, signing books with lines of people who are eager to discover what I actually look like, and getting late night dinners with bookstore owners after a whirlwind evening of talking about myself. Spinning is a graphic novel about growing up as a competitive figure skater. I talk about the expectations and challenges of being a young girl in that sport, while also dealing with coming out of the closet in Texas.

This is my first real book tour. I’m only 21, which tends to lead to agonizing expressions and eye rolls from a lot of older authors. And being a young, gay woman on a book tour for my graphic memoir has been exactly what you might expect: bizarre and wonderful.

It’s bizarre because so many people are surprised by what I have to say. They think that because I’m so young I don’t have enough real experiences to share. And that’s the moment where I launch myself into stories and use every tactic I’ve ever learned about public speaking to show them I do know what I’m doing. I tell them about moments in Spinning, about how I knew I was gay when I was 5, about the grueling practices and competitions, about how art gave me a connection to myself and a career at the same time. And I talk about how publishing a memoir is so healing because it let’s others hold your memories with you.

After I’m done baring my soul to audiences, people come up to me. They talk to me, they ask me questions, and they tell me about themselves. There was a father who thanked me for being a young successful lesbian that his daughter could look up to. There was the young woman who was having a hard day and simply cried with me. There was a young boy who aspired to one day draw Lumberjanes and wanted to know how he could make that happen. And then there were all the queer teens who simply wanted to share a piece of themselves with me after I had with them.

I think a lot about these moments. And I think about how what really matters about Spinning is not necessarily that it has queerness in it, but that it was made by me, a real queer person. That’s what I see people tapping into. And so much of the conversation about diversity seems to revolve around the content of our books, when really in my mind the focus should be entirely on the creators. True diversity comes from diverse voices.

I think about the queer kids along the way who have shown me their own comics, or who have shared their aspirations to create one day. And they often ask me if they should do a memoir, of if they should try and write a hard, honest story about themselves. I can see that they want to be a part of something, that they want to have an impact. But I always tell them the same thing. If you’re queer and you’re making things, your only job is to make what you want. We benefit from it all. The happy fantasies and the crime novels and the memoirs and the fan fiction. Diversity doesn’t require some hardened, tragic, real life perspective. It only requires that diverse people have a platform to share stories in any form that they want. In Spinning, I wanted to talk about the world of competitive figure skating from my own perspective. I wanted to talk about bullies, my first love, the dangers and beauty of childhood, and finding your identity in a sport where individuality loses you medals. Spinning is a piece of me. I drew every page with care and honesty. At times it was scary to share such a personal story, but I’m so glad I did.

Tillie Walden is a two-time Ignatz Award–winning cartoonist from Austin, Texas. Born in 1996, she is a recent graduate from the Center for Cartoon Studies, a comics school in Vermont. Her comics include The End of Summerand I Love This Part, an Eisner Award nominee. tilliewalden.com

Spinningis available for purchase.

THE EPIC CRUSH OF GENIE LO was definitely not the first book I’d ever written. Back when it only existed as a single chapter and some ideas about the characters, I was trying to get a completed middle grade book off the ground. I attended a writer’s workshop with a group critique session, hoping to get the insight I needed to finally make my MG work viable.

Once I arrived at the conference, however, I was told I’d been sorted into a YA critique group. This kind of thing tends to happen when your last name is at the end of the alphabet. Everyone gets sectioned off into the teams/groups/classes that are available in A to Z order, and as someone who arbitrarily fails to make the cutoff, you get to fill whatever’s left open.

So I pulled an audible. Instead of reading from my middle grade book, I read the opening pages of GENIE LO, which were pretty much unchanged from the published version, if you’ve seen those already. And to my surprise, the group liked it! They told me it was funny and attention-grabbing, which was exactly what I’d hoped for.

Then they asked me how the story and characters would develop. “What’s Genie like?” someone asked. “What’s her dominant emotion?”

“She’s angry,” I said.

The room kind of turned when I said that. I could see the hesitation in the group.

“Angry against injustice?” someone offered, trying to add a helpful qualifier to my description.

Well that too, I remember thinking.

I could have been reading too much into that moment. And I certainly am not denigrating critique groups at writers’ conferences; the very same people at the session helped me flesh out what THE EPIC CRUSH OF GENIE LO would eventually become. I owe them a great deal. But I do remember that one little hitch in time where it took a bit of mental effort for them to reconcile an angry protagonist with a sympathetic one.

Genie is overtly frustrated with what can be a dehumanizing process for many at her age—college applications. The idea that you can be denied opportunity and self-actualization by a gatekeeper who won’t even spend that much time judging you is maddening. I saw a fictional parallel where other creators have before, in Sun Wukong’s struggle to gain acceptance among the gods. But I also saw a personal one in the post-college career difficulties I was having at the time. The fight to be accepted as worthy never really ends. Or at least that’s how I felt about it.

Further complicating matters is when life doesn’t even let you focus on your own fight, and demands that you do some heavy lifting for others. In Genie’s case, she has to protect her town from an invasion of demons who won’t let well enough alone, simply because she happens to be the strongest one around. Important tasks often fall to the people who are already working the hardest, not to those with the most time and resources on their hands. I wanted to write about this in a way I hoped people would recognize, visible under the action and comedy and romance.

Anyway, if you want to see what happened when I doubled down on Genie being angry rather than back away from the characterization, you can check out THE EPIC CRUSH OF GENIE LO when it comes out on August 8th.

F. C. Yee grew up in New Jersey and went to school in New England, but has called the San Francisco Bay Area home ever since he beat a friend at a board game and shouted “That’s how we do it in NorCal, baby!” Outside of writing, he practices capoeira, a Brazilian form of martial arts, and has a day job mostly involving spreadsheets.

The Epic Crush of Genie Lo will be available for purchase on August 8th!

I was in the car with all four of my kids one day, when they launched into a strange sort of competition.

My oldest son said he was glad he had autism (which he does) and not Addison’s Disease—like his sister—because she had to take a lot of pills every day, and he never had to take pills. He didn’t like taking pills.

My second oldest son said he’d rather have Celiac Disease (which he does) than either autism or Addison’s Disease, since all he had to do was avoid gluten in his diet.

My daughter countered by insisting that her “thing” was better than either of her brothers’, since she could eat whatever she wanted to, unlike her Celiac brother, and swallowing pills was no big deal to her—she’d become a pro at it since her diagnosis at age five.

My youngest son was silent throughout most of this argument, but he finally spoke up. “It’s not fair,” he said. “I’m the only one who doesn’t have anything.”

There was a pause, and then his sister said reassuringly, “Yes, you do! You have allergies!” He brightened up. “Yes!” he said. “That’s true! I have allergies!”

This was many years ago. They’ve all been busy since then in all sorts of ways. The son with Celiac Disease came out of the closet his senior year of high school, graduated from college, and now works in entertainment. The daughter with Addison’s Disease was also eventually diagnosed with Hashimoto’s, OCD, and an anxiety disorder, and is currently a very happy college sophomore. The son with autism is an outstanding artist, whose work has appeared in a bunch of different exhibits. The one with allergies is now applying to college.

They’re all dealing with stuff and succeeding at stuff and occasionally failing at stuff, and have no desire to fit into any kind of “normal” standard or ideal.

I adore my kids. I mean, obviously I love them, but I also like hanging out with them and laughing until I can’t breathe. They’re kind, openminded, curious young adults, who care about social justice and want to make the world a better place for everyone, not just an elite few. And I think all the various ways in which they’re different from their peers helped make them like that.

The truth is, diversity always makes a community more thoughtful and interesting. A society where everyone looks, thinks, acts and worships the same way is stagnant and dull. Add in different backgrounds, viewpoints, beliefs, and needs, and it becomes vital, interesting, and relevant.

I want our country to not just tolerate differences: I want us to revel in them, to appreciate how much better we are when we’re not all striving to fit a mold. One of the things I learned in researching autism is that all the students in a class thrive when a student with special needs is included. Why? Because teachers can’t assume everyone learns the same way. They have to try out new and creative ways of teaching, which benefits the whole class. And yet parents will frequently protest when a kid with special needs is included in a mainstream classroom, insisting it will harm their kids academically.

The problem is, we’re hardwired to be suspicious of anyone who’s different—probably something to do with the importance of sticking to your pack back in primal days. We’re all too quick to be afraid of what we don’t know. People have to be taught to be comfortable with differences, and entertainment is a good way to make that happen: fiction can help you get to “know” the kind of person you might never meet or might actively be avoiding in real life.

My most recent YA novel, Things I Should Have Known, is about two sisters: Ivy has autism; Chloe doesn’t. They’re loyal and supportive and love each other a lot—but also get annoyed and frustrated with each other, the way sisters do. They both fall in love. They both get their hearts a little broken. They both get to be important characters, and they both get to struggle and celebrate and mess up. I want my readers to root equally for them both, to love them both—and, in the process, without even realizing it, to stop seeing autistic people as something alien.

(By the way, there’s also a major LGBTQ storyline in the novel, but because it sneaks up on you in the book, I’m not going to say any more about it.)

Anyway, my point is: diversity enriches a family; diversity enriches a community; and diversity enriches a novel.

Also? Don’t tell my son but his allergies were actually pretty minor.

Claire LaZebnik is the author of five novels for adults and five YA novels, including Epic FailandThings I Should Have Known. With Dr. Lynn Kern Koegel, she co-authored the non-fiction books Overcoming AutismandGrowing Up on the Spectrum. She has written for The New York Times,The Wall Street Journal, and Self Magazine, among other publications, and contributed a monologue to the anthology play Motherhood Out Loud. Please check out her website at www.clairelazebnik.com or follow her on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter.

I don’t have a daughter yet, but if I did, I would have taken her to see Wonder Woman. And I’m sure she would have been enamored as much as I was. It’s also safe to assume she’d be a young black girl, and while enjoying the movie, she would instantly know Wonder Woman doesn’t look anything like her. She might even go so far as to ask, “Mommy, I like Wonder Woman, but can I be Wonder Woman?’

The movie was progressive and (for the first part) fun, but its lack of intersectionality made it like many other superhero and fantasy series, in that women of color can only enjoy it to an extent. Wonder Woman didn’t have the diversity I want for empowering my future children. It had the kind of diversity that plucks a few POC at random and throws them into an all-white world, that makes them sidekicks and tokens, that others them. Wonder Woman isn’t the only movie to do this, and plenty of YA fantasy book series do it, too. When I have children of color, I want to be able to give them a fantasy series where they don’t have to ponder why the heroes and heroines never look like them. I don’t want them to feel like they must blend into the mainstream, into whiteness, to be powerful and strong.

My debut novel, The Blazing Star, is about a sixteen-year-old black girl named Portia who travels back in time to ancient Egypt, kicks butt, and saves the world. She also takes her twin sister, Alexandria, and a classmate, Selene, on the journey with her. They, too, are women of color. And smack dab in the middle of The Blazing Star’s cover is Portia’s face looking off in the distance, ready to wield her #blackgirlmagic as she sees fit.

I’m not sure how many other black girls are on the cover of YA fantasy book series, and I’m not sure how many lead their own stories as protagonists. But judging by Lee & Low’s annual research, the number is incredibly low. I was hell-bent on my book series doing what traditional pub is dragging its feet to do—fixing the representation gap—a major component of why I went indie. I received the “can’t connect with the voice” rejections from agents over and over, but knew there was an audience for The Blazing Star. Sure enough, it sold out on release day.

What I love most about the series is that I know my future daughter will never have to ask if she can be Portia. She will just know she can by picking up The Blazing Star and seeing a black girl on the cover. And when the second book in the series, The Falling Star, releases in February 2018, there will be another beautiful black girl on the cover, and my future daughter will know she can be Alexandria, too.

My parents gave me a wonderful (no pun intended) gift thirty years ago. They surrounded me with black dolls and books with black protagonists, which permitted me to see myself not as the Other, but as normal. As a well-rounded, complex person with likes and dislikes and experiences that matter like anyone else’s, and who knew her black skin was beautiful just the way it was. It was my parents’ mission to ground my normalcy in my agency, not in my proximity to whiteness. Perhaps that education, that pedagogy of possibilities, is why I sold my car and put the money toward publishing the first in a YA fantasy series starring teens of color. It’s not a series about tokenism. It’s about agency. It’s a love letter to my fascinating sisters and to my future children. It’s beyond diversity—fantasy or not, at its heart, my trilogy is reality.

Imani Josey is a writer from Chicago, Illinois. In her previous life, she was a cheerleader for the Chicago Bulls and won the titles of Miss Chicago and Miss Cook County for the Miss America Organization, as well as Miss Black Illinois USA. Her one-act play, Grace, was produced by Pegasus Players Theatre Chicago after winning the 19th Annual Young Playwrights Festival. In recent years, she has turned her sights to long-form fiction. The Blazing Star is her debut novel.

The Blazing Star is available for purchase.

Even before there was Ghost in the Shell, there was LUCY. Admittedly, it was pretty much agreed that LUCY was a crappy movie all round, but I only had to suffer the trailer to know that it was not for me. It opens with ScarJo kidnapped by Taiwanese mafia type, before she gives the bad boys the ass kicking they deserve. Asian mafia/triad/gang is a western media trope hollywood falls upon time and again. But what really got me was when ScarJo escaped, she was shouting “Do you speak English?” and then shooting Taiwanese who didn’t. Sure, maybe it was another triad baddie, but WTF ever. The fact that Hollywood did not see the heavily racist overtones of this opening scene is unsurprising… and infuriating.

So in one of the first major Hollywood movies where my birth city is featured on the big screen, ScarJo is shown gunning down Taiwanese men and demanding that they speak English. *insert appropriate RAGE gif here*

I joke that I write All Asian All the Time. But it’s not really a joke if it’s true, is it? WANT is my first near-future thriller set in Taipei with a cast composed entirely of Asian and Pacific Islander characters, and a Taiwanese hero featured prominently on the cover.

WANT is the first YA set in Taiwan I am aware of released by a bigger US publisher, and definitely the first YA SF. The cover art was designed by the amazing Jason Chan, and my audio book is narrated by Chinese American actor Roger Yeh. I had requested an Asian voice actor and my awesome audio book publisher honored that request! You can listen to a sample of Roger’s fantastic narration here.

It hasn’t been an easy journey. Publishing is a rough business, period, but when you’re insisting on writing novels with basically entire Asian casts, your story is seen as too niche, an outlier. Asian Americans have been othered in western media from the beginning, and it comes as no surprise this was also the case in young adult novels.

There is no greater compliment for me as a writer than to have a reader tell me they could see my books made into a movie, but also probably nothing as heartbreaking. I know my narratives are too western for Asia and too Asian for the west to garner interest from film or dramatic rights. It would be too much of a risk, too big of a leap. As Americans, we’ll accept immigrant stories from Asian Americans (and not much else), we’ll admire and ogle the “exotic” Asian backdrops, costumes, customs, culture, and women. But Asian faces will still be relegated to the background as side characters to provide some “authenticity” and lend to the Asian ambiance.

These are not the stories I write, friends. And I will continue to put Asian protagonists at the forefront of all of my stories. I celebrate each publication as a triumph, and my heart is lifted by the young Asian American creators and storytellers I see rising to tell their own tales—to bring to life what we personally never got to see as young readers.

WANT releases June 13th and can be purchased (mostly) where all books are sold. Or you can order through my favorite indie Mysterious Galaxy Books to receive signed and personalized copies (while supporting indie, woohoo!) and I’ll include gorgeous art swag by Jason Chan and myself.

I’m so thrilled to share WANT with you, readers. I hope you fall in love with these characters and Taipei as much as I love them.

AddWANT to your goodreads.

Cindy Pon is the author of Silver Phoenix (Greenwillow), which was named one of the Top Ten Fantasy and Science Fiction Books for Youth by the American Library Association’s Booklist and one of 2009′s best Fantasy, Science Fiction and Horror by VOYA; SerpentineandSacrifice(Month9Books), which were both Junior Library Guild selections and received starred reviews from School Library Journal andKirkus, respectively; and WANT (Simon Pulse), also a Junior Library Guild selection, is a near-future thriller set in Taipei. She is the cofounder of Diversity in YA with Malinda Lo and on the advisory board of We Need Diverse Books. Cindy is also a Chinese brush-painting student of over a decade. Learn more about her books and art at http://cindypon.com.