#15th century

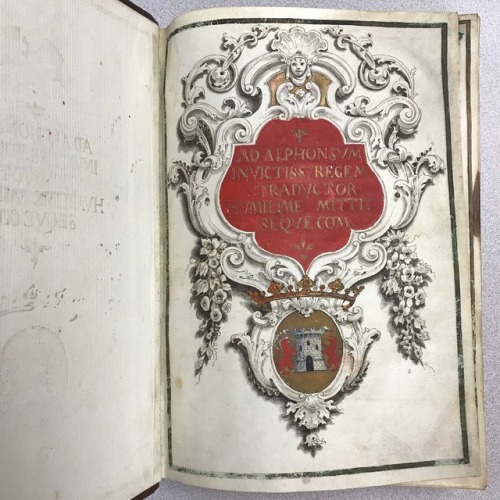

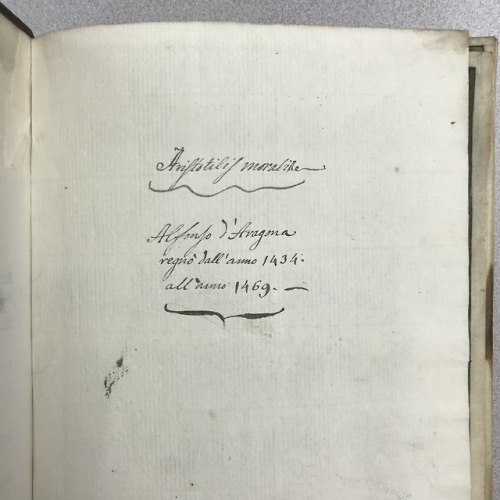

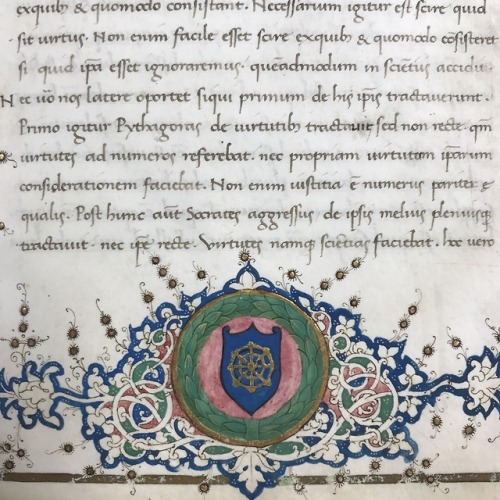

Our rare book catalogers are nearly finished cataloging this rare and elegant copy of Giannozzo Manetti’s translation of Aristotle’s Magna moralia and Eudemian ethics. Only four other copies are known to exist.

Post link

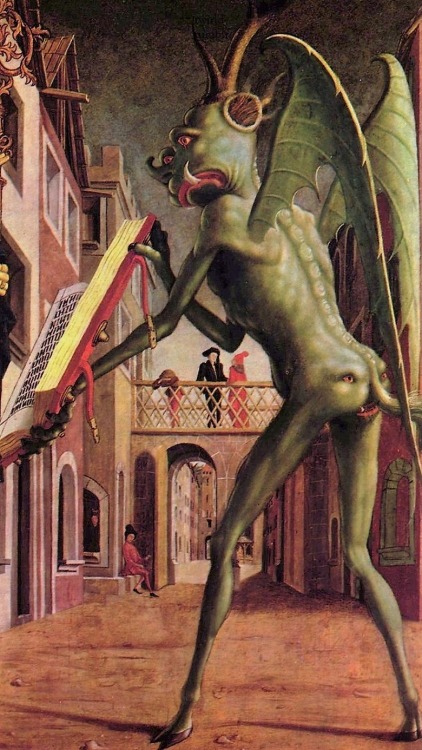

Dante Alighieri, Divina Commedia, prima cantica : Inferno. Con l’Ottimo Commento. 15th century. Illuminated by Bartolomeo di Fruosino and his atelier.

Post link

Dante Alighieri, Divina Commedia, prima cantica : Inferno. Con l’Ottimo Commento. 15th century. Illuminated by Bartolomeo di Fruosino and his atelier.

Post link

God blessing the animals he created. Look at all the little details, there’s so much talent here!(found in Postilla in Bibliam(Tours - BM - ms. 0052) made by Nicolaus de Lyra in France somewhere around 1500).

Source:

- “Enluminures”(culture.gouv.fr)

Post link

The man with the blue hat / The man with the ring

Art by Jan van Eyck

.c. 1430

December 1st 1463 saw the death of Mary of Guelders, Wife of King James II.

Mary of Guelders was born circa 1434 at Grave in the Netherlands, she was the daughter of Arnold, Duke of Guelders, and Catherine of Cleves. Catherine was a great-aunt of Henry VIII’s fourth wife Anne of Cleves.

When she was twelve years old, Mary was sent to Brussels to live at the court of her great uncle Phillip, Duke of Burgundy and his wife Isabella of Portugal, where she served as lady-in-waiting to the Duchess of Burgundy’s daughter-in-law, Catherine of Valois, the daughter of Charles VII King of France.

Marie, or Mary as she became known in Scotland had been earmarked to marry Charles, Count of Maine, but her father could not pay the dowry. Negotiations for a marriage to James II in July 1447 when a Burgundian envoy went to Scotland and were concluded in September 1448. Philip promised to pay Mary’s dowry, while Isabella paid for her trousseau. Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy settled a dowry of 60,000 crowns on his great-niece and Mary’s dower (given to a wife for her support in the event that she should become widowed) of 10,000 crowns was secured on lands in Strathearn, Athole, Methven, and Linlithgow.

William Crichton, Lord Chancellor of Scotland was sent to Burgundy to escort her back and they landed at Leith on June 18, 1449. Her arrival was described by Chronicler Mathieu d'Escouchy. She first visited the Isle of May and the shrine of St Adrian. Then she came to Leith and rested at the Convent of St Anthony. Both nobles and the common people came to see her as she made her way to Holyrood Abbey in Edinburgh.

Marie was 15 and James 19 when the two wed on July 3rd and immediately after the marriage ceremony, Mary was dressed in purple robes and crowned Queen of Scots. Consort by Abbot Patrick.

A sumptuous banquet was given, while the Scottish king gave her several presents. The Queen during her marriage was granted several castles and the income from many lands from James, which made her independently wealthy. In May 1454, she was present at the siege of Blackness Castle and when it resulted in the victory of the king, he gave it to her as a gift. She made several donations to charity, such as when she founded a hospital just outside Edinburgh for the indigent; and to religion, such as when she benefited the Franciscan friars in Scotland. The couple had six children, the oldest James, became James III.

James II died when a cannon exploded at Roxburgh Castle on August 3rd, 1460, before his death he had ordered another castle be built for his wife who was left to oversee it’s construction as a memorial to him, Ravenscraig was still being built when Marie moved into east tower. She also founded Trinity College Kirk in Edinburgh’s Old Town in his memory, she herself died and was buried there in 1483, the old Kirk was demolished, amid protests in 1833 and Marie was interred at Holyrood Abbey.

The pics are of the Queen and their Wedding Feast by Gerard de Nevers

Post link

The Ladies♔Princesses → Isabella Stewart, Duchess of Brittany (1426 - c.1495/99)

Isabella of Scotland was born in 1426 as the second child and daughter of James I and Joan Beaufort. Although there is no details of her childhood, a report before her marriage describes her as being “a well-brought-up young lady, schooled to silence and submission.” By the age of sixteen she married Francis I, Duke of Brittany in front of Bretons and Scottish nobles on 30th October 1442. The marriage appears to have been cordial and the couple had two daughters. In 1450 Francis died and Isabella was pressured by her younger brother James II to return to Scotland, where he had hoped to arrange a second marriage for her. However, Isabella refused, claiming that she was happy and popular in Brittany; along with being too frail to travel. It was more than forty years later, when Isabella died as early as 1495 and as late as 1499, and lived long enough to see the reign of her grandnephew James IV. She was either buried in Nantes or Vannes.

“In both piety and patronages, she could be matched by others in her world. Her life is of interest, nevertheless, because it provides precious evidence of the tastes of one particular woman, shaped by current fashion in devotion. Beneath the splendid trappings and ceremonial routine appropriate for her rank, Isabella attempted an internal pilgrimage as a private soul, a day by day progress on a path to spiritual enlightenment.” — Elizabeth Ewan and Maureen M. Meikle (editors), Women in Scotland c.1100 - c.1750

Post link

Miniaturist German, active 1480s in Regensburg

[Eva] The Salzburg Missal, ca.1478/89, Manuscript (Clm 15708-712, 5 volumes), 37.7x27.5 cm

Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich

This manuscript, composed of 5 books, contains 22 masses for the most important feast days of the ecclesiastical year in Salzburg Cathedral. It was produced in Regensburg where the illuminator Berthold Furtmeyr (c. 1435-1506) was active. His major achievement is the Salzburg Missal. Producing the monumental Missal took more than a decade and required three consecutive patrons, the archbishops of Salzburg.

One of the finest miniatures of the manuscript (on folio 60v from volume 3) shows in the central medallion the Tree of Death and the Wood of Life, according to a conception of medieval theology. (wga)

Post link

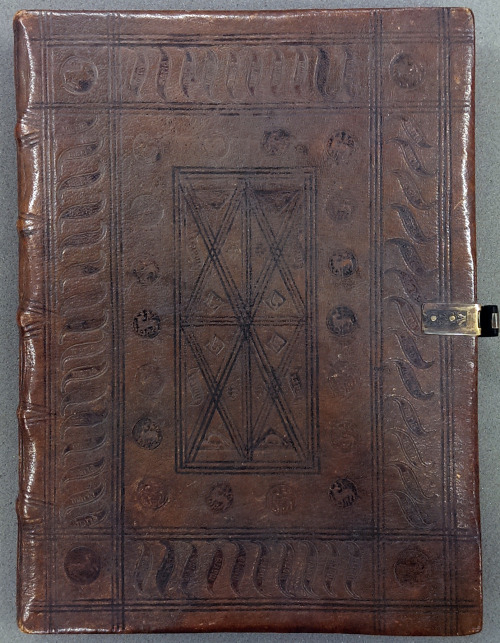

If you’re in the habit of reading descriptions of old books—and why wouldn’t you be?—you’ve likely come across something described as bound in period style or in a sympathetic binding. This typically means the book was rebound relatively recently, but rebound in a style consistent with the time period of the book’s original publication.

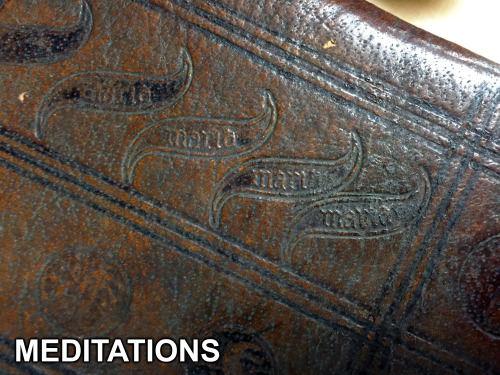

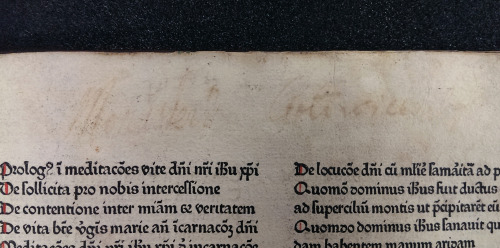

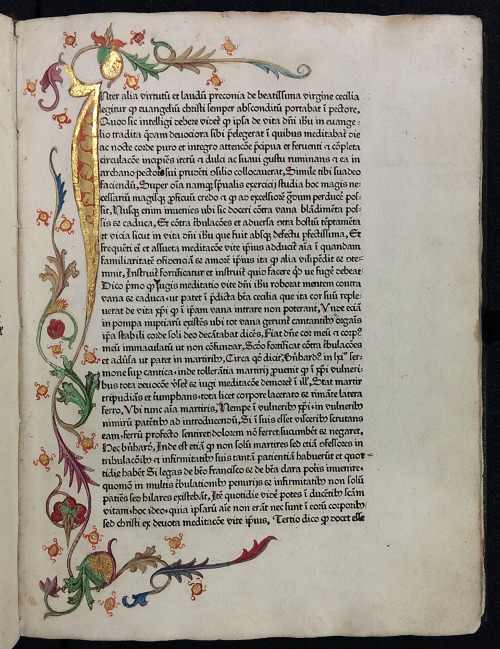

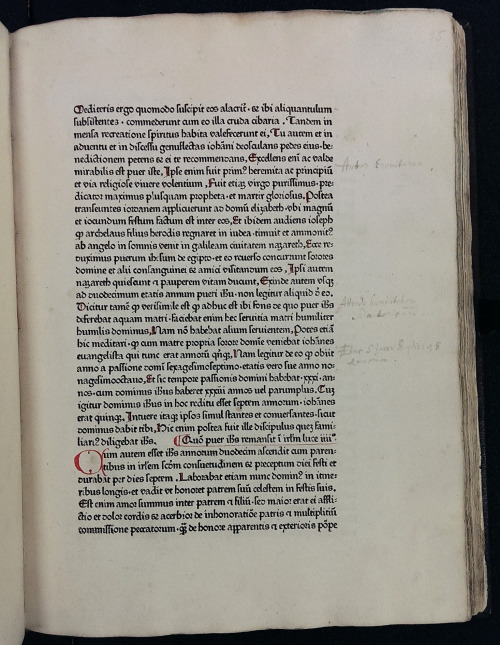

For example, our first edition of the Meditationes Vitae Christi (Meditations on the Life of Christ) was rebound in such a way. You can read more about this work—a recent acquistion—here.

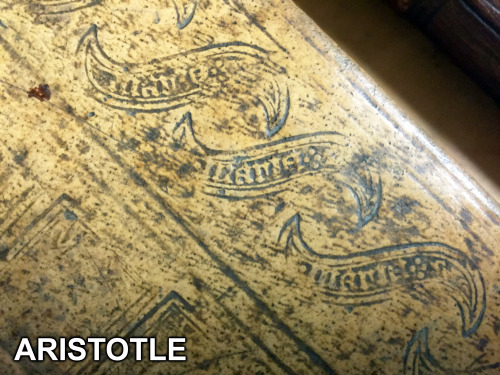

And shortly after the Meditations arrived, we received the first printed Greek edition of Aristotle (it was a very good summer), which underscored just how well done this period-style binding was. Although the books were likely bound about 400 years apart—the Aristotle around 1500 and the Meditations around 1900—the styles are strikingly similar. The combination of borders built up from different tools, surrounding a central diaper pattern, was a familiar style when both were published. The Aristotle binding is almost certainly German, so it’s no surprise that the binding of the Meditations, which was printed in Augsburg in 1468, emulates a 15th-century German style.

Of all the similarities, what most caught our eyes was a particular tool used to decorate the boards. While obviously similar, small differences distinguish them. The Aristotle version, for example, has four tiny dots following Maria, while the Meditations version has no dots; a double border surrounds the Aristotle tool—thick on the outside, thin on the inside—while the Meditations tool has a single border; the Aristotle tool measures over 3 cm from end to end, while the Meditations tool measures just under 3 cm. The sheer volume of such tiny differences among tools is staggering. The Einbanddatenbank, a database of 15th- and 16th-century finishing tools used on German bindings, records more than 600 versions of the Mariatool.

How do we know the Meditations binding isn’t original? There are a number of clues, the general as-new appearance being a big one, but subtler evidence is there. The spine edges of wooden boards were commonly beveled in the late 15th century, but they aren’t here. Spines were seldom decorated at this time, yet the binder of the Meditations couldn’t help but to add some restrained decoration. Could these features be found on bindings from the late 15th century? Sure. But the accumulated weight of the evidence favors something done later in period style.

Make no mistake, the Meditations binder was good. Even the endpapers are period-appropriate leaves removed from an old book. This binding was absolutely the product of a skilled craftsperson with a thorough understanding of period styles—and perhaps the product of a binder with the skill and patience to make their own finishing tools.

~Pat

Post link

One way to measure the popularity of a given text is to count the number of times it’s been published. For example, the immense popularity of The Imitation of Christ, which went through 78 editions in the 15th century, has been said to trail only the popularity of the bible itself as a devotional text. Compare these to 15 editions of Dante’s Divine Comedy in the 15th century and one can begin to appreciate just how popular Christian devotional literature once was. As it happens, MSU has one of just eight known copies of a rare 1495 editionofThe Imitation of Christ.

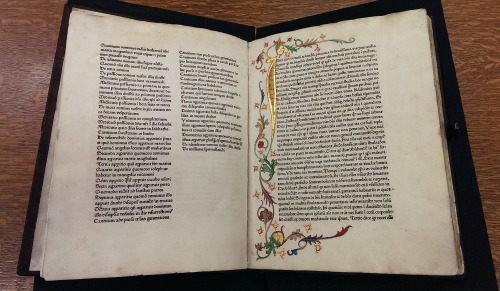

Not far behind the popularity of The Imitation of Christ, with at least 65 editions appearing in the 15th century, is the Meditations on the Life of Christ. MSU is very fortunate to have recently acquired the first printed edition of the Meditations—the very first of those many editions to appear in the 15th century (pictured above). Published in 1468, this edition has the distinction of being the first dated book printed in the city of Augsburg—and this at a time when fewer than a dozen cities in all of Europe had the technology to print books. This first appearance in print is a fine complement to our medieval manuscript of the text, and it also claims the honor of being one of the three oldest printed books to reside in Michigan.

On the front paste-down of our Meditations, afloat in a sea of booksellers’ annotations, is the bookplate of Hieronymus Baumgartner (1498-1565), a powerful advocate of the Protestant Reformation. Baumgartner enrolled at the University of Wittenberg in 1518, the very town in which just a year earlier Martin Luther allegedly nailed his Ninety-five Theses to a church door. In Wittenberg, Baumgartner befriended prominent reformers Philipp Melanchthon, Georg Major, and Joachim Camerarius, and he later helped found the Melanchthon Gymnasium in his hometown of Nuremberg in 1526. Baumgartner was an accomplished statesman, to be sure, but we’re particularly pleased because his bookplate, as far as we can tell, is the oldest bookplate in MSU’s collection.

~Pat

This Provenance Project guest post was written by Patrick Olson, Rare Books Librarian at Michigan State University Special Collections.

Post link

![hildegardavon: Miniaturist German, active 1480s in Regensburg[Eva] The Salzburg Missal, ca.1478/89, hildegardavon: Miniaturist German, active 1480s in Regensburg[Eva] The Salzburg Missal, ca.1478/89,](https://64.media.tumblr.com/8f350d9328f96f2fe56aed57cbc1b000/a0e8f008e8d534dd-c3/s500x750/27731fab7b50d936d8344c9b7d427ab246586f4e.jpg)